Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Newsletter

Among Us: the too-close-to home terror of Mister Organ

The reviews all seem to agree: Mister Organ, the newest film from journalist David Farrier, is disturbing. It’s strange. It’s unsettling. It’s funny. It’s very, very good. Having seen it myself at a Q&A screening last night, I can definitely attest to how creepy the film is. But the depth of the creepiness — and the genius of the film — goes a lot further than it’s easy to explain in a normal review, so I’m going to try another way.

Among Us

A few years ago, long enough now that distance has taken the bleeding edges off the event, my mum and stepdad got in some terrible trouble. At the time, they lived on Russell Island in Moreton Bay, near Brisbane. The island is, and remains, one of the strangest places I have ever been. I’ll write about it at length, one day. For now, it’s enough to say that despite many promises and plans, Russell Island has never had a bridge to the mainland. The only way to get there is by ferry, and this inconvenience meant real-estate prices on the island weren’t soaring the way they were elsewhere around Brisbane and the Gold Coast. Mum and her partner were desperate to sell their house, another piece of land they owned on the island, and get away before prices on the mainland got too far out of reach. And one day, they met someone who said he could help.

His name was Zach Mar, and he — with some help from a local woman — had created a scheme called Display Partners. The idea was, very loosely, that you’d give Display Partners money, and they’d work with a builder who’d use your investment to build a display home, at a very low cost. The builder would rent the home from you and show it to potential clients, and after a few years, you’d have a beautiful home that you could move in to or rent.

A screenshot of the defunct Display Partners site, as archived by the Wayback Machine. Just look how happy those stock footage models are! Sounds good, right?

Perhaps a little too good?

You know where this is going.

I only found out about my mum’s involvement with Display Partners through unnerved reports from my brothers, and Mum’s own Facebook posts. Those were the first warning signs. When I asked her about it she was uncharacteristically cagey. Something seemed off, so I got digging.

A year or few earlier, I’d picked up some odd skills from hanging around a motley group of people I knew online and IRL. We’d recently become obsessed with a rapidly-deepening rabbit hole on the topic of “Competitive Endurance Tickling.” Comprised of David Farrier, Dylan Reeve, me, and a several other people, the Tickle Friends would unearth a lot of the material that ended up in the documentary Tickled. Now, I put what I’d learned about internet sleuthing to use, prying into Display Partners.

I learned that Zach Mar aspired to a playboy lifestyle, with a yacht and other rich-guy amenities, and that he ran charity events for disabled children. That he’d only recently arrived in the Bay Islands, that he’d convinced many people into investing in Display Partners. That he used several other names, all variations on the Zach Mar theme, and that no-one seemed to know who he really was or where he came from.

And I found that he’d run real estate scams all over Australia.

I was terrified for my mum. I let my brothers know what I’d found and called her. To my dismay, she was angry, and distant. She implied that I didn’t trust anyone, that she’d known I would try to interfere. But during the call she let slip that my sister and her partner had got involved. The idea was that Zach, a real-estate genius, would help them buy a house.

I nearly booked a ticket to Australia on the spot, which would have taken all the money I had at the time. Instead, I called my sister, who didn’t sound pleased either.

“They’re just helping us buy a house!” she said. “Zach knows so much about it, you should hear him talk. He knows a way we can do it without having to pay all this money up front.”

“That’s fine!” I said. “If he’s just helping you get through the process of buying a house, there’s no trouble! The important thing is that you don’t try to get around the law, or give him any money up front.”

My sister went silent.

“Have you given him any money?”

She didn’t say anything. I panicked.

“These people are evil!” I yelled. “They’re scammers. Don’t give them a single cent. If you give them money, you’re going to lose it all! You have to believe me!”

I shed a few angry tears after the call. I didn’t know what else to do. I was sure my sister had given these people her money, and that they would steal it. But what if I was wrong and had wildly overreacted, slandering someone who was actually trying to help my sister out?

It wasn’t until months later, when I finally made it over to Australia for a visit, that I learned what had happened.

My sister had indeed trusted the people behind Display Partners with some money. After another panicked call, this time from my brother, my sister got in touch with the woman Zach Mar was working with, and demanded the money back.

That wouldn’t be possible, the woman said.

I wasn’t present, but I know what happened next. I’d witnessed my sister get properly angry a few times as a kid. I was older than her by two years, but I got the hell out of the way when it happened. She turned into a fucking Valkyrie, all ice and fury and razor edges.

She told the woman that if the money wasn’t back in her account by the following morning, they’d be hearing from her workplace’s extremely competent and high-priced lawyers. She hung up.

The money was back in her and her partner’s account by the deadline. The amount: their life savings. An entire house deposit.

This event was a domino that helped topple the Display Partners scam, as it did indeed turn out to be. I could go on for a whole documentary’s worth of madness and skullduggery, but I’ll just give you the finale. My mum couldn’t brook the threat to her daughter and told Display Partners she wanted out too. They turned nasty. Battle lines were drawn: believers versus skeptics, with believers terrified that the scrutiny from skeptics would torpedo their investments. The tight island community seethed at each other. Lawyers, journalists, state officials, and detectives all got involved.

Mum and her partner eventually got out, having lost a few thousand dollars. They escaped with some of their savings, and their house. Others were not so lucky. A number of people — mostly older, mostly retired — lost everything they had.

Afterward, my family and I put things together again. My sister was grateful. My mum was too, but she and her partner felt terrible shame over the episode. “We just feel so stupid,” her partner told me. But they weren’t. They were trustworthy, kind people, which made them think other people would be trustworthy too. The scammers took full advantage.

Zach Mar disappeared.

Despite some real effort, I never managed to speak to Zach or see him in person. After he vanished, the closest we got to closure was a rumour that he’d crossed the wrong people and got beaten to a barely-alive pulp. Hearing this made me feel sick. I wanted to see him pay, but not like that. Real life is messy. It doesn’t often offer satisfying endings.

I’d always meant to write a proper story about this, but for a long time it felt too close. Gradually, I let it go, along with the thought of writing it up. Then I watched Mister Organ, and it brought the whole terrible episode roaring back.

You don’t just watch Mister Organ. The character is described as a void, and that’s the thing with voids: they watch you right back. Don’t misunderstand — the film is really funny, full of the kind of odd folly that can’t help but make you crack up. It got more audience laughs than a lot of comedies. But it stays with you in a way that’s not comfortable. Leaving the theatre, I felt like I’d come away from Mister Organ with a little bit of Michael Organ in my head. Lurking, peering, giggling, talking.

It’s not a spoiler to say that Michael Organ talks a lot. Like, three hours at a time, without stopping. Of course, this isn’t in the film, which lasts a swift 95 minutes. (At the Q&A, I was tempted to ask if there’d be a DVD extra that’s just footage of Michael Organ talking non-stop, for three hours. David, if you’re reading this, this is a really good idea and you should do it.)

The talking at length thing fascinated me. After the film, I thought about all the other times I’d seen similar behaviour. Marketing copy for sketchy products on weird websites that go on forever. The endless screeds of QAnon and anti-vax conspiracy theorists. The droning babble of scammy pastors and preachers. “Nigerian” 419 scam emails filled with capslock and dubious claims of royalty. Tickled star David D’Amato’s ranting, furious, constant emails, and the many websites he created, full of wild claims and slander.

Talking at length in this way is not just something that scammers do because they love the sound of their own voices (although that’s part of it). Dismissing it as ranting is a mistake, because con-artists do it for a reason. If you find yourself being talked at in this way, there is a chance you are a mark. You are being tested, probed, winnowed. 419 scam emails are long and loaded with nonsense to filter out skeptics. If you still maintain any belief by the end of one of their rambling screeds, they’ve got you. Even if you’ve never read a scam email, you’ve seen this behaviour before — in the strange, rambling, self-obsessed droning of the incredibly dangerous narcissist who starred in The Apprentice and would later serve time as the 45th President of the United States.

Zac Mar loved to talk too, my mum told me. He’d come and drink her tea and coffee and talk and talk and talk. The people he preyed on thought he was a real-estate genius who was going to either help take away their troubles, or make them some much-needed money. Mister Organ reminds me of him, and of the fact that there are Mister Organs everywhere.

It’s this that makes Mister Organ the most powerful film I’ve watched in a long time. Everyone should see it. It’s a case study in disturbance, and an explainer on how dangerous people operate, how they prey on others. How they’re so hard to pin down, so hard to stop. It’s also a brilliant example of journalism done right, of its remarkable power to shine a light in dark places, to protect the innocent, to give dignity to victims — and to warn the unwary.

I wish the film had come out ten years ago, and that my mum had seen it back then. Witnessing Organ’s tactics and the effect he has on other people might have saved her a world of hurt. Instead, I’ll settle for telling you to watch Mister Organ as soon as you can.

Find session times and buy tickets for Mr Organ at flicks.co.nz.

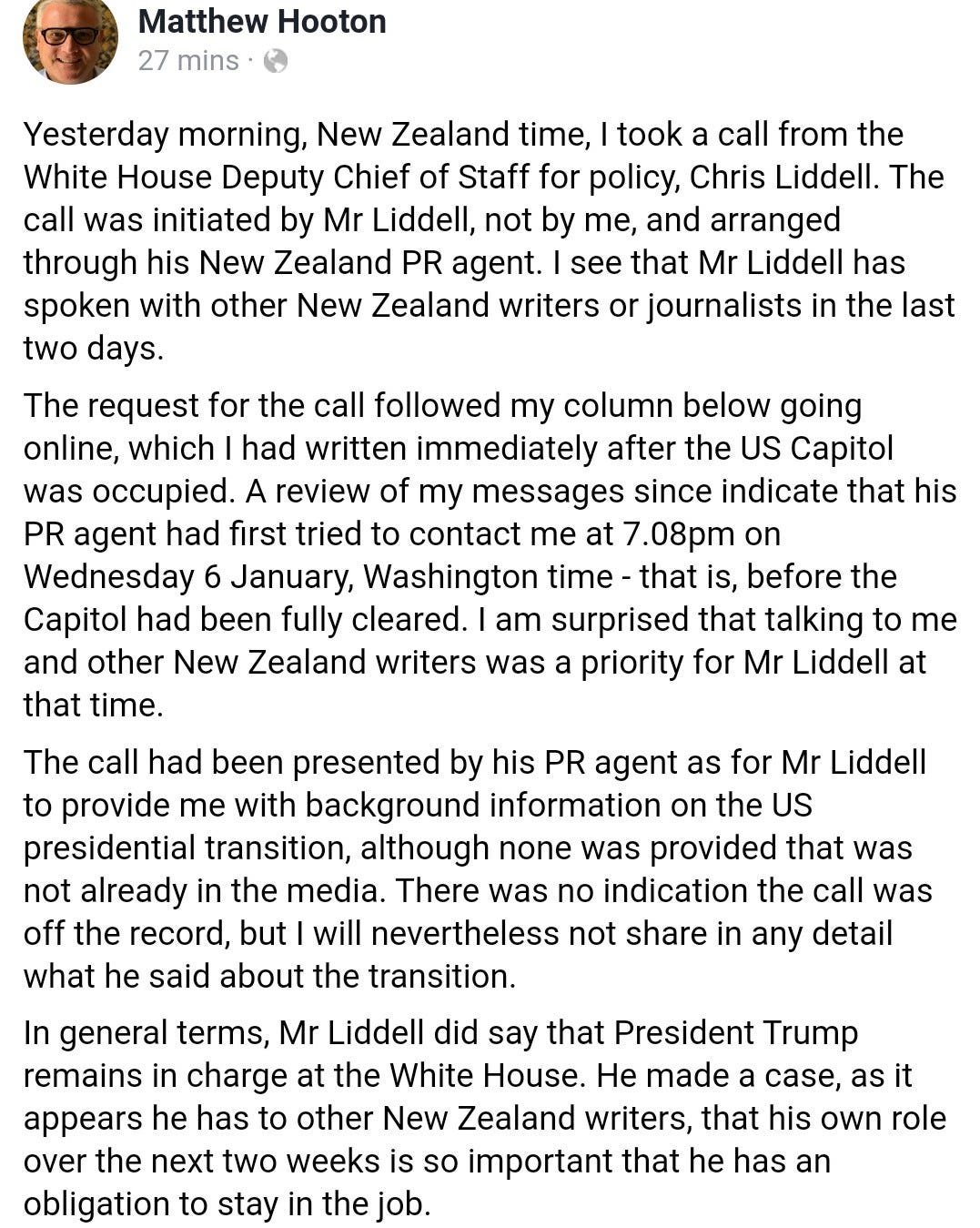

The Problem(s) With Twitter

I’ve been on Mastodon for about five minutes now and it’s safe to say I like what I’ve seen.

Of course, because it’s Mastodon, I’m not on “Mastodon.” That’s like saying “I’m on email.” As far as I can tell, Mastodon is just the protocol for a whole bunch of different social networks that can all talk to each other. I’m on mastodon.nz, which looks like a good, welcoming community. It’s raw, a bit clunky, scattershot, off-kilter. Already, it’s striking how different it feels from Twitter, or at least, what Twitter has become.

I never really fit in on what everyone is now calling “the bird app.” It became clear, pretty quickly, what you needed to become big on Twitter. If you had a following from outside the app, like being an author or a Kardashian, it was easy enough. Or if you had a specialism, like actual deep science or tech knowledge, your following tended to aggregate around those wellsprings of knowledge. But to become a big deal on Twitter via Twitter itself, you needed to Post. You needed to adopt a personality or posting archetype and double down on it. A lot of the time, the personality adopted was, well, kind of horrible, or at least it was in the political and journalism circles I followed. An post-ironic, world-weary, ultra-supercilious personality dominated. Permanently angry, yet arch and distant. You could be mad about stuff at the same time that you were flippantly dismissing everyone else who was actually mad about it because, You, the Poster, were Above All That.

I didn’t like it but at the same time, it molded my online personality. It affected everything and everyone on Twitter. If you wanted your stuff to get seen, you had to Post, and even if you were genuinely earnest or enthused about something, the precedent of coating it under pearlescent layers of post-irony was almost unavoidable.

And then there’s the other kind of Poster, which is the sort that finds the worst stuff in the world and signal-boosts it for clout.

It’s an understandable instinct. We all want to avoid being associated with bad out-groups, right? And to know who the bad out-groups are so we can avoid them? And of course journalism is often highlighting bad things. But, importantly, journalism offers context — or at least, it does when it’s done right. On Twitter, simple virtue-signalling was immediately weaponized, often by sociopaths who recognized that outrage was a perfect path to acquiring a following. They made great use of it. For a while, I tried to spend my time online suggesting that signal-boosting your political and ideological enemies was wildly counter-productive, but this was never popular. People just got mad at me. “But this guy! Look how bad he is! Look at the terrible thing he just said! No-one should have to see this! I’m going to show it to everyone!” Arguably, this behaviour is what ultimately gifted the world President Trump. On New Zealand Twitter, with its blessedly lower stakes, look-at-this cloutposting reached its nadir when terminally online lefties started screenshot-mocking the National Party social media pages for making memes incorrectly.

They’d been played. National, utilizing the either the services or the tactics of Tory-friendly agency Topham Guerin, was committing design crimes like poorly-labelled graph axes or using uncool fonts specifically to wind up terminally online lefties who would then signal boost their political ads for free. It was brilliant. Instead of articulating their actual ideas or values, which might win allies, an online army of lefties had been deputized as water-carriers for their own opposition.

One of the reasons I like Mastodon is because there are specific mechanisms and server rules that might help to disincentivize this infuriating, self-defeating habit. For example — with the obvious disclaimer that I am new and don’t know much about how it works yet — it seems that on mastodon.nz, you’re encouraged to hashtag political stuff, or chuck a content warning on it. It’s about choice. If using hashtags is standard, users can filter out stuff they can’t be bothered with, or specifically zero in on it. If very specific content warnings for controversial content that go beyond just “NSFW” are normalized, it’s always up to a user whether they want to see it. It might finally be an end to oh my god, this stuff is disgusting! Let’s show the world!

The federated nature of Mastodon instances is also looking like a real boon. In the Dawn of Everything which has become my “no, really, you absolutely must read this, ideally yesterday, but I’ll settle for right now, look, here are some bits I’ve highlighted or memorized” book of the moment, authors David Graeber and David Wengrow make the case that indigenous societies in pre-colonization North America featured vastly more social mobility than our world does today. There was constant, radical experimentation and flux across different nations or tribes. If you didn’t like the way a given nation did things, that was (often) fine. You could leave, and find a new nation that was more to your liking. The authors suggest this happened frequently, and that, fascinatingly, many indigenous people traveled far further than it’s common for people to do today. Then the hegemonizing, colonizing forces arrived. There was now one way to do things and you couldn’t leave. My way, without so much as a highway. In Margeret Thatcher’s infamous words: there is no alternative.

Just like we’ve got used to living in extremely similar nation-states where we can’t easily experiment with new ways of doing things, we’ve become inured to an Internet world where there is no alternative. The corporate consolidation of the Internet has given rise to an often-joked-about status quo (posted, of course, on Twitter).

I’m old enough to remember when the Internet wasn’t a group of five websites, each consisting of screenshots of text from the other four.

— Tom Eastman (parody) (@tveastman) 7:28 PM ∙ Dec 3, 2018

We’ve all become used to how bad Twitter is, like frogs broiled in a collective pot of Posting. It’s taken Musk’s terribly-executed takeover as Main Character-in-Chief to shock a lot of us into looking for an alternative. Plenty of people, including me, had already drifted away. I’d deleted the app on my phone and only dropped in occasionally on the web interface where adblockers and other plugins made the experience sporadically tolerable. But now, instead of drifting apathy, there’s a real mood to look for alternatives.

Naturally, people are worried about what that might entail. I’ve seen prolific Twitter users who use the platform to advertise their livelihood worry that their reach will be circumvented on a federated platform like Mastodon. And that’s understandable, but you also need to know that if you were on any of the big platforms, your reach was already being artificially curtailed. If you built a platform on a Meta property, like Facebook and Instagram, your ship sailed a long time ago. Want people to see your stuff? Pay up. The last major platforms where unmonetized virality is possible are YouTube, Reddit, and TikTok (and, email, sort of). YouTube is already a morass of a few top creators trying ever more desperately to game the algorithm and trust me, you’re not as good as they are. Also, making videos is hard. Reddit is a double-edged sword: it sometimes works for creators who need to be discovered, but the site’s culture and moderators have an inherent, bizarre hostility to creators sharing their own stuff. These rules are enforced sporadically and the fate of your self-promotion will often fall to the whims of whoever is modding a particular subreddit on a given day. Redditors moan constantly about a lack of original content, somehow missing the point that much of the site has rules against posting original content. If you make stuff, your best bet for being seen on Reddit is for one of the site’s many semi-professional content thieves to steal it, post it without consent or attribution, and for someone in the comments to recognize it and drop a link to your Instagram or YouTube.

I have no idea what the deal with TikTok is. I’m too old for that shit.

But if you are a creator on Twitter, chances are your reach has been bounded for a long time. No matter how many followers you supposedly had, if you were posting there, your content was being algorithmically curated, and was probably being shared and signal boosted by one small set of people who the algorithm had pegged as liking your stuff. If you that set was big enough, you were probably doing fine, but if not, well. Unless you are a very successful Poster, you have probably got nothing to lose by going to Mastodon, where the lines designating the borders of different communities are clear, instead of invisible and arbitrarily enforced by proprietary algorithm. A small audience that’s 80 percent engaged is, potentially, much better than a large audience that isn’t engaged at all.

I’m not sure why I’m writing this screed, which has turned into more of a missive, or possibly even a treatise. I suppose it’s because discovering Mastodon has me wanting to write and share stuff again. The idea that there might be an audience (however small) that is interested in anti-inflammatory discussion of the things I’m interested in is intoxicating. I love the idea of making things without feeling like my creativity is being invisibly shaped by algorithmic necessity, the thought that I can post without Posting. I have this FDR quote knocking around in my head: “Bold, persistent experimentation,” and the feeling that it’s what I need, what the internet needs, and what the wider world could do with. It feels like there’s once again a welcoming wall against which I can throw stuff, and see if anything sticks.

At last, there is an alternative. But not just one. There are lots of them.

See you there. And also here.

Needless F****** Things

I’ve always wanted to make a living as an artist, but so far, life hasn’t found a way.

What’s frustrating is not that I’ve had no success; it’s that I’ve had some. Just enough for a taste. When I marshal my scattered attention for long enough, I can mix my humour and limited painting ability into some weird blends that people seem to genuinely dig and that I’m still proud of.

Over several years, I painted and auctioned weird portraits of New Zealand politicians the rest of the world is lucky enough not to know about, which went a tiny bit viral. Partly because of this, I managed to finagle a place at an illustration convention called Chromacon. The only problem was that I didn’t have much to exhibit.

Birds with Hats:

What to paint? I like birds, but I needed to differentiate myself from hundreds of other Kiwi artists who like birds too. I also like Lord of the Rings, and silly puns. As an experiment, I painted a Riroriro (Grey Warbler) wearing a wizard hat, and called it Gandalf the Grey Warbler.

I enjoyed the joke and the painting so much I did three more just like it, quadrupling my last five years or so of art output in about two weeks. I got some prints and an online shop made in time for the exhibition, and as an afterthought, I put some pics up on Reddit. My post got popular enough that quite a few people bought prints. Success!

A real live human:

Josh’s latest creation – a human child! A few years later, having painted several more birds, I started a YouTube channel where I painted scenes from video games using techniques learned from watching living meme Bob Ross. This was just starting to get a bit of traction when my wife and I received my best excuse yet for not making art: a baby. I didn’t paint or draw anything for about 12 months — until David asked me to do some illustrations for the Webworm I wrote about climate change.

That’s most of the highlights from the last ten years. While it’s fair to say there’s been some success on the art front, my artistic inconsistency — plus the opportunity cost of leaving a job that pays for one that mostly doesn’t — have tanked the idea of doing art full-time.

So when I saw a Webworm article on how some artists were making a living from NFTs, I was genuinely interested.

The only problem was that NFTs are built with the same technology that powers cryptocurrency. And I know just enough about crypto to hate it.

Pollution, monetized

To my mind, cryptocurrency is explained most brilliantly by The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy. Typically, author Douglas Adams managed to do this despite having died eight years before Bitcoin first appeared. The scene: a bunch of humanoid aliens (comprised of the “useless third” of their planet’s population, which includes marketers, management consultants, and documentary makers) have crash-landed on prehistoric Planet Earth and are looking to set up a new society. Here, let me plagiarise:

“If,” the management consultant said tersely, “we could for a moment move on to the subject of fiscal policy. Since we decided a few weeks ago to adopt the leaf as legal tender, we have, of course, all become immensely rich.”

Ford stared in disbelief at the crowd who were murmuring appreciatively at this and greedily fingering the wads of leaves with which their tracksuits were stuffed.

“But we have also,” continued the management consultant, “run into a small inflation problem on account of the high level of leaf availability, which means that, I gather, the current going rate has something like three deciduous forests buying one ship’s peanut.”

Murmurs of alarm came from the crowd. The management consultant waved them down. “So in order to obviate this problem,” he continued, “and effectively revalue the leaf, we are about to embark on a massive defoliation campaign, and. . .er, burn down all the forests. I think you’ll all agree that’s a sensible move under the circumstances.”

Critics who actually lived to see crypto have been even less kind: it is, they say, valueless except as a greater-fool investment; a truly colossal, tech-driven Ponzi scheme that gets by on market manipulation and an endless supply of newbies hoping to get rich.

You could, of course, make a similar claim about the global financial system, neoliberalism, or even capitalism. Banks create money from nothing, leverage crisis for record profits, and lobby against regulation. Wall Street is a corrupt casino run by byzantine financial interests with extraordinary wealth and influence on power. We’re entering a new monopolistic era where there are a few dozen hyper-corporations driving inflation through rampant profiteering, and a million minnows fighting over scraps.

Those who profit most from this fundamentally unjust system face no consequences; instead they squirrel away their multi-billions in quasi-legal tax havens or blast themselves into space for kicks. Meanwhile, the exhaust gases from this great, mindless machine are setting our only home ablaze as increasingly panicked millions try desperately to puzzle out what the fuck to do. It’s not hard to see why people are so emotionally invested in what looks like an alternative.

But cryptocurrency is just another head of the same hydra, and contrary to its name, it doesn’t really work as currency. As corrupt and unjust as the financial system is, at the end of the day, I can buy food with the fiat currency that appears in my account each week, sent in exchange for the labour I put in at my job. The transactions flash through in seconds – from my job to my account, from my account to the supermarket. This is not true of crypto. The biggest currencies have decentralized databases so big and so unwieldy that transactions can take hours, or days.

Of course, there are use cases for cryptocurrency. It’s fantastic for speculation, scams, blackmail, unregulated market manipulation, and buying illegal products on the dark web. While those things are obviously problematic, it’s made much worse by the fact that all those transactions don’t just take a long time; they use an incredible amount of energy. As of 2021, Bitcoin alone used more electricity than a country the size of New Zealand.

A proof-of-work cryptocurrency like Bitcoin or Ethereum relies on cracking harder and harder math problems in order to verify transactions. While the actual mechanics of this are beyond me, this is roughly what “mining” is: computers compete to verify transactions, and winners get thrown a crumb of coin to incentivize them to keep going. All this computing activity requires enormous amounts of electricity, which comes from either a) burning carbon or b) using renewable energy that could be powering homes, but is instead powering a rack of gaming GPUs.1

Here’s the simplest way to put it: Proof-of-work cryptocurrencies are monetized pollution. They might be the most asinine example of late-stage capitalist absurdity yet invented. I wasn’t always this cynical about it; years ago I even did a bit of freelance work for some really good people at a crypto outfit that used a less environmentally ruinous approach called “proof of stake”. But after watching the field for a decade or so and seeing the technology produce nothing useful, I just kind of tried to ignore it.

Enter NFTs

When NFTs appeared, it appeared that crypto might finally have a decent use case. Even more fascinatingly, that use case seemed centered on enabling artists to make a living from their work. When David’s Webworm about Richard Parry – an artist I’ve admired from afar for a long time, thanks to our overlapping interests in art based on puns, birds and video games — appeared in my inbox, I was fascinated to see he was making an absolute killing. Others were doing even better. Mike Winklemann, aka Beeple, sold a single NFT for $69 million. Nice.

I had a look online to see what people were saying. My Twitter bubble, made mostly of artists and journalists, hated NFTs. But Twitter hates everything — cynicism is currency and a great way to gain followers is to look savvy by being a snide know-it-all. So maybe that wasn’t the best source. I checked elsewhere. Some tech sites were cautiously optimistic, others dismissed NFTs as a grift.

It seemed I couldn’t find an off-the-shelf opinion I was happy with. So I tried to purge myself of preconceptions and go in fresh. I would do my own research.

This… may not have been a good idea.

I’ll talk more about what I found shortly, but first I should explain what NFTs actually are. An NFT is a receipt. Simple, right? But because the blockchain adds layers of needless complexity to even simple concepts, I guess we’d better dive into yet another crypto rabbit hole.

Needless Fucking Things

The acronym “NFT” stands for “non-fungible token.” What does that mean? While it sounds vaguely mycological, all it means is that it’s a record of a transaction that lives on the blockchain, that can’t be altered, and that can store a small amount of data. Which, in itself, means nothing. It’s just a string of numbers and letters. Look, here’s an NFT. Gaze upon it — this thing last sold for $25 million USD:

Like leaves, or snowflakes, every NFT is unique. They’re also like leaves in that they don’t have any inherent value. In fact, you could argue NFTs have even less inherent value than leaves, because leaves remove carbon from the atmosphere and NFTs do the opposite. They differ from leaves in one important respect: unlike most digital properties, which are designed to be copied, NFTs are made to be scarce, because they’re on the blockchain. (As in Douglas Adams’ prescient example of burning down forests to make leaves more valuable, the blockchain creates artificial scarcity by burning carbon.)

As humans, we’re used to assigning value to random things. The paper my New Zealand dollars are printed on isn’t really worth anything, but because we collectively agree that money is both scarce and representative of the value created by economic activity, worthless paper acquires value (signified by some special artwork) and I can exchange it for goods and services.

Because an NFT is just a string of numbers corresponding to a blockchain file, its value comes not from scarcity alone, but also the information it stores. Individual Ethereum entries can only store a small amount of data, so NFTS are often just links to something else, usually a digital file stored on a server. These files can be pretty much anything — jpegs, video game assets, documents, you name it. An NFT says: “see that thing? Well, this guy has an NFT of it.”

This is where it gets thorny. Having an NFT isn’t in itself proof of ownership of the file it’s linked to; it’s just proof of… having an NFT. Ownership in society is usually assigned through a central authority: the law and its enforcers. For example, if I nip into the Louvre and grab the Mona Lisa, the local centralized authority — the French Government — will be unhappy, and they will express their sadness by throwing me in jail. But if I copy a file linked to an NFT, no-one can do jack shit. Even if I steal someone’s actual NFT, by hacking or trickery, the legal remedy is often unclear. The blockchain itself has no answer for this, because it’s very hard to undo transactions and is decentralized by design.

To date, few in the NFT scene seem to care about the philosophical plot holes underlying the technology. The attitude seems to be: if enough people agree something has value, ipso facto, it does.

Mad world

Does all that make sense? Of course not. But what people are doing with this technology is even weirder. If you want a headache, you can go and dig all this stuff up yourself, or simply visit the acerbic NFT disaster documentation site Web3 is going just great, but here are some high points of a journey I’ve now spent months on, increasingly bewildered by the new absurdities our cyberpunk dystopia creates.

- A bunch of techbros had an artist create a bunch of disgusting ape jpegs which they released as collectible NFTs that also get you access to a Discord server. In a less cursed world this would have earned yawns, or derisive laughter, but instead the Bored Ape Yacht Club has made them all bajillionaires. Not long ago they got former indie music darlings The Strokes to play an exclusive party for ape enthusiasts. Formerly reputable magazine Rolling Stone even did a puff piece on them (which was also sold as an NFT.)

- AMC, Gamestop, Ubisoft, Meta (aka Facebook) and many other large companies are cashing in on NFTs and the nebulous term “metaverse.” Even Funko Pops, those ugly vinyl collectible toys, now come with NFTs — even one debasing the memory of my favourite kitsch-art mentor, Bob Ross. Quick-moving start-ups have beaten the big companies to market, with games like The Sandbox, where you can make shitty low-poly yachts with entirely fictional features and sell them for $650,000. People from low-income countries toil in these virtual mines, earning crypto to buy bread.

- Celebrities, smelling a quick buck, have gone all-in on NFTs. Musician Grimes, former partner of a crypto enthusiast called Elon Musk, sold $6 million realdollars worth of the things. Melania Trump, partner of a frequently-bankrupted real-estate grifter, released her own line of NFTs. Absurdly, some people saw fit to buy them.

All that is just skimming the top of the crypto-NFT cesspool from the last year or so. Every day there’s some new absurdity, some ridiculous boondoggle. Just look at this dire low-energy digital “rave” that some poor cryptobro has to pretend is fun, probably because it cost an ungodly amount of money.

This is the #metaverse… A live rave happening right now in @decentraland for the upcoming @LightbulbmanNFT release by #BjarneMelgaard. Music from @feedelity @prins_thomas @mightbetwins #NFTdrop #rave #virtualevent #NFTCommunity

— Alex Moss (@alexmoss) 12:18 PM ∙ Jan 20, 2022

Then there’s the infinite horror of the promotional video for a thing called Cryptoland.

The best way I can describe this video is: in the movie Event Horizon, Sam Neill’s character gets a glimpse of hell. Cryptoland is what he sees.

Perhaps it was madness kicking in, but as I squinted harder into the seething migraine glare of the NFT scene, I began to see a bigger picture — a meta-picture, if you like.

The more I looked, the more NFTs seemed to have in common with another unreal scene populated by quick-buck entrepreneurs, grifters, fantasists, money-launderers, and the elite: the world of contemporary art.

Ce n’est pas une scène

To call contemporary art a grift is unfair to grifts. It is an all-encompassing, money-spinning, massively-multiplayer game of The Emperor Has No Clothes. To explain it in detail would take a few years, so you’ll have to settle for the short version: Contemporary artists compete to be platformed by a shifting roster of ultrarich patrons and insufferably smug critics who act as taste-pimps. To attract attention, artists deliberately court controversy. This race to the bottom ends up creating and celebrating ridiculous shit, offensive shit, or sometimes actual shit. And the most important rule of Contemporary Art Club is this: no-one involved in propping up this tottering edifice of absurdly overvalued literal garbage can ever admit that it’s anything less than 100 percent serious.

The real art is in making the absurd seem valuable and important, and very few artists succeed at it. This doesn’t matter, because it’s not really about artists. The system exists for the near sole benefit of the One Percent, who are incentivised to take up art appreciation by the substantial speculation opportunities, tax benefits and/or money-laundering opportunities it provides. Here’s arts patron (and former Act party branch chairman) Chris Parkin, explaining why the 2020 Parkin Drawing Prize went to an entry that was not a drawing. It explains the fundamentals of the grift better than I ever could.

“The judges are always looking for something innovative, something that’s gone a bit beyond … it almost invariably [was going to be] something that doesn’t look in any way the conventional sense like a drawing.

“It’s totally unpredictable … it’s a recognition that nothing in art succeeds like recognition.”

There are essentially two tiers of art: real, serious contemporary art, and everything else. Artists who prefer to focus on craft — often making “genre” art that normal people like and elite gatekeepers hate — are usually denied entry to the potentially lucrative contemporary art world. Sometimes, they’re lucky enough for their work to be co-opted (frequently without consent and/or after death) by critics wielding the demeaning term “outsider artist.”

Being unwilling to prostrate yourself before the contemporary art establishment usually means either working a day job or scraping by selling originals, prints, and merchandise, or setting up a Patreon. Success in this part of the art world is rare, is usually very hard-earned, and doesn’t even begin to compare to the fortunes amassed by successful contemporary artists like Damien Hirst.

I’d argue that NFTs are a permutation of the contemporary art model, but with a much bigger pool of participants. The world is awash with the newly crypto-rich, who can be anyone from actual investors to the lucky people who bought Bitcoin when it was cheap for shits and pizza giggles. For those who bought early and managed to “hodl,” NFTs represent something new: the ability to actually do something with your crypto.

Instead of buying black market goods, trading for other forms of cryptocurrency, or cashing out for actual money (and being taxed accordingly), you can now speculate on artwork. Both contemporary art and NFTs are a boon for money-launderers and greater-fool grifters, but NFTs make it faster and easier. If you need to instantly hose down some dirty money, just buy an NFT! And if you have a bunch of crypto burning a hole in your wallet and you’d like to make some more, just follow these four easy steps:

- List an NFT for sale

- Create a new crypto identity and buy your own NFT for a ridiculous price. Congratulations, you’ve just artificially inflated its value!

- Now you can set any price point you like for your NFT. Make it look like a bargain. “Wow, I just bought a million-dollar NFT for ten grand! What a deal!”

- Profit.

Naturally, the contemporary art machine has embraced the new grift with its many sinuous arms. Sotheby’s, one of many high-priced auction houses favored by the ultra-rich, partnered with auction site Nifty Gateway to sell The Pixel, which is literally just an NFT of a single grey pixel, for $1.3 million. The emulation of this controversy-first aspect of contemporary art might also explain why many NFTs are valued highly despite being hideously ugly.

Just look at these horrible things As an artist, I…

Let’s take a step back. If artists are benefiting, does it really matter that NFTs have devolved into hype-driven memetic profiteering? To answer this question, let’s consider what an artist actually needs. We’ll do this in the time-honored form of… user stories.

As an artist, I need my work to be recognized and popular.

Can NFTs help? Maybe. If there are a bunch of cryptobros hyping up your art because they hope it will help make them rich, you’ll get popularity by proxy. However, many in the art community hate NFTs and the spammy, toxic atmosphere they generate. For a lot of artists, it may not be worth getting involved. But it’s clearly working well for some: an artist called Seneca used their profile as lead artist for the Bored Ape Yacht Club to sell NFTs of unrelated art for 23.7 ETH — at the time of writing, about $57,000 USD.

As an artist, I need for my work to be protected from theft or appropriation.

Can NFTs help? Lol, no. Art theft is rife online, and NFTs may be making it even worse. Before NFTs, one of the best ways to make a quick buck off someone else’s artwork was to put it on a t-shirt and hope you sold a few before you got caught. Now, anyone can grab your jpeg, mint it as an NFT, and make off with the proceeds. This has already happened to many high-profile artists who want nothing to do with NFTs.

As an artist, I need to be able to make a living / money from my work.

Can NFTs help? As we’ve seen from the cited examples, the answer is very much yes — if you’re very lucky. Evidence suggests that most artists are not making a killing, much less a living, from NFTs. Most sales bring in a mere pittance. To succeed, you need either an existing profile, or a unique hook that gets you noticed by someone with a lot of cryptocash to burn. A time machine might also be necessary: since the initial media frenzy, a lot of the heat has gone out of the NFT market.

NFTs also claim to make it possible for artists to profit from not only the first sale of their work but subsequent sales as well. I love this idea. While the notion of royalties has been around forever, and some countries have resale royalty schemes, it doesn’t apply to many artists. An easy, accessible alternative would be huge. But on closer inspection, it doesn’t seem to hold up. Royalties can be skipped altogether if future buyers simply switch blockchains.

So, where does this leave us? The utility of NFTs for artists seems mixed, at best. What’s more, the tide of public opinion seems to be turning. Proposals by Ubisoft to shoehorn NFTs into one of its videogames were met with fury from gamers, who are already sick of being nickel-and-dimed with real-money microtransactions. Even Beeple thinks that NFTs are “an irrational exuberance bubble.”

Then there are signs that crypto itself is tottering. While the death of cryptocurrency has been reported many times, only for it to rise again, it still has a potentially fatal flaw. Ultimately, cryptocurrency only has utility if you can cash it out for actual money. There are only a few ways to do this, using crypto exchanges and “stablecoins” pegged to a fiat currency like the US dollar, and these are coming under increasing regulatory scrutiny. China and several other countries have banned crypto outright, and other nations are toying with the idea. As I write this, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other cryptocurrencies are tanking, with the market falling by over $1 trillion, in just a few days.

Despite all this, and despite being explicitly decried by the originators of NFT technology, the gold rush continues. Corporations are pivoting to crypto. Randoms are hoping to get rich. And artists are still trying to make a living from what they love. Some are even succeeding. Me? I’m going to stick to my principles and stay right out of it.

Just kidding.

For sale: my integrity (and artwork)

The one piece of advice I’d be prepared to offer other artists is: if you don’t want to sell a given piece, put it up for sale anyway — but at an intentionally, ridiculously high price. It’s a rare win-win for the cash-strapped: either you get to keep the thing you want, or you get enough money for it that you don’t mind. I’ve done it before with a couple of my paintings. Now I want to try the same thing with NFTs.

It’s long been my broadly-held belief, exacerbated by reading some libertarian dickhead called Nozick at law school, that everyone has their price. The theory goes, broadly, that while there remain some things that no amount of money will compensate for — your own life, the lives of your loved ones, etc — there’s a lot of stuff in life for which, when the chips are sufficiently down, you’ll take a payout. It’s definitely true for me. Ultra-wealthy mega-corporations like Block (Twitter) and Meta (Facebook) are embracing the ridiculous crypto-NFT-metaverse nexus. Why should I abstain, when just one good deal with the crypto devil could set my family up for life?

The idea of selling out is also motivated by a growing frustration. I’ve got just enough art experience and skill to know I could do a lot more. I just lack the time. Before I start to sound too self-indulgent, I should stress that being able to pursue art as a hobby is highly privileged, in the scheme of things. I have a good job and an incredible family. I don’t regret prioritizing a more traditional career over art for their sake — I have pretty strong childhood memories of food bank Christmases — and I’m well aware that being a working artist is, well, hard work. But I still want to do more. I just need the time, and to buy time, you need money. I’d settle for some kind of decentralized sugar daddy.

This is compounded by the fact that all the ridiculous things I see succeeding in the NFT scene are things I can do. Perhaps incorrectly, I think I could do many of them much better. Making up ridiculous meta-narratives to sell art? I did that with my viral-ish auctions, and each of my bird artworks already has a goofy little story to go with it. Exclusive communities? Sure, why not. I’m pretty sure I can set up a Discord server. As for creating art that’s worth a lot of money? As we’ve seen, it’s subjective, but I can sure as hell make stuff that looks better than these horrible fucking lions.

I don’t like NFTs or cryptocurrencies. Nor do I like the global financial system, or neoliberalism. But — for now — this rigged system is the only game in town. Without money, I can’t play, even if my only reason for wanting to is creating positive change, or having some kind of security for my wife and little boy. And I’m starting to see how tenuous that can be. The Covid-19 pandemic continues. Climate change continues. When it comes to these and other crises, governments the world over have sacrificed human lives on the altar of business continuity for wealthy power-brokers. The message has never been clearer: you don’t matter — unless you have money.

So I’m trying one last Hail Mary, with the biggest project I’ve ever attempted. I’m taking everything I’ve learned about NFT success and applying it to the most popular thing I’ve ever made: my paintings of birds wearing hats. And along the way I hope to either:

a) help prove NFTs are mostly useless for artists, or

b) eat humble pie and admit NFTs are great, actually.The price of this humble pie? It starts at the low, low cost of… my mortgage.

That’s right: in the finest NFT and contemporary art tradition, I’m creating something utterly ridiculous, and putting an equally ridiculous price on it. Does it have any real value, any actual artistic merit? Of course not — unless you think it does. In which case, happy bidding.

This story originally ran on David Farrier’s Webworm and a follow-up piece (or two!) is edging ever-closer to completion, so I figured it was time I exposed my readers to Part One. Last time I wrote here I said I wanted to do something different and, well, this is about as different as it gets. I’m turning on comments so let me know what you think: I’m always interested in people’s feedback and — especially on this topic! — good-faith critique.

If you liked this piece (or hated it) the best way to show your support (or furious opposition) is to share it far and wide. Show your friends or bring all your mates in for a furious denouement; every little helps.

And if you really liked it, or you want to foster my lifelong dream of doing strange and/or helpful things for a living, the below button will help you give me your hard-earned money.

This bad Covid column is everything wrong with opinion journalism

What valuable insights does a sports writer have into pandemic management?

According to Stuff, the answer is “enough to publish an entire column about it.”

So here’s a bit of a blow-by-blow of said column, authored by one Mark Reason. Who is Reason, you ask? According to his Stuff bio, he worked for the Telegraph, which is a kind of newsletter for British Tories, and before that, he “read English” at Cambridge. After reading his column, you may find yourself wishing he had read a bit more, because it’s the bad-prose burp beloved of opinion sections everywhere.

Before going any further, let’s answer the obvious question – why am I bothering to dissect this column? I didn’t really want to write another one of these things — I burned myself out pretty hard on the last one — but, after two years of a global pandemic, it still blows my mind that the New Zealand news media intentionally elevates the views of people who by definition know absolutely fuck-all about epidemiology, medicine, science, or apparently anything except for (maybe) sports.

It’s not a particularly egregious example of the bad-Covid-take genre; there’s a lot worse out there, best exemplified by the daily shit speech from the NZME stable. But that’s kind of why I’m interested in this one — it’s so goddamn dull. The most banal of bad takes. Rather than taking on something worse, I’d rather examine why this particularly boring example was the one that bothered me enough to actually write something.

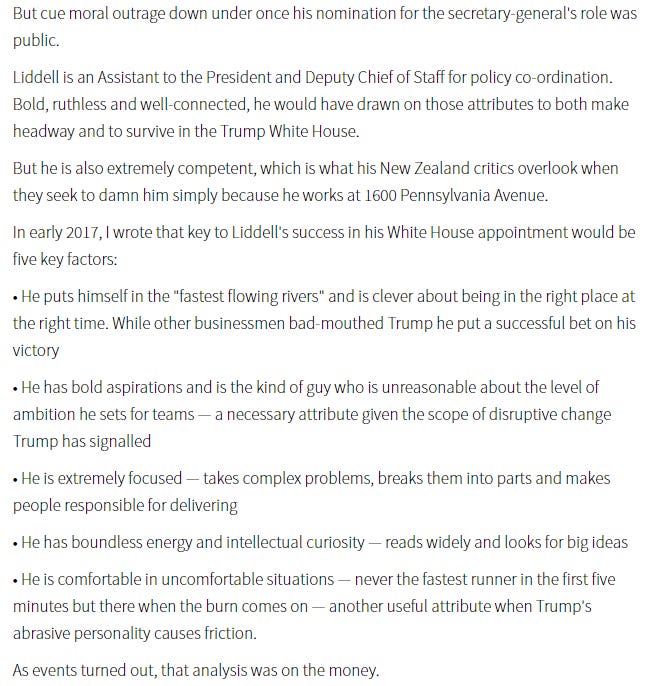

Let’s begin with this headline

This is a terrible headline, but to be fair to Reason, he probably didn’t write it. Sub-editors usually write headlines, and this one is just rubbish – there’s no wit, no snap, not even any real reason to click. It’s trying to be a riff on “I fought the law and the law won” but it just ends up being an overlong bore. Bad sub, zero points. Let’s move on to the actual article.

Ah, OK, I get it. It’s not actually about Novak Djokovic. It’s about Mark Reason! Djokovic is just the hook to hoodwink the audience into thinking the column might have something useful to say. But let’s zoom in a bit. We’ve got a clumsy metaphor — kids drawings vs soldiers. And sure, soldiers are spooky. Why are there soldiers?

Well, that might be because a few of the people obliged to quarantine in fully-catered hotel rooms kept trying to escape. But let’s look a little closer. You know where else has sworn officers of the state just kind of looming around to make sure people “follow the rules that her government has imposed”? Literally the entire country. They’re called “the police.” The “rules her government has imposed” also has a more common, less clumsy name: it’s called “the law.” And, all discussions of the problematic nature of policing and punitive justice aside, both police and law are kind of a fixture. Try not to panic when you see cops after you get out of MIQ, Mark.

Let’s keep calm and carry on.

“Unless you count being stuck in a lift with Tiger Woods for a decade.” What? What even is that? What does it mean? To what does it refer? Why are you torturing the “stuck in a lift with X” cliché like this? I’m picking on this bit because it’s so strange to me — golf is one of the few sports I actually follow to any extent, and Tiger Woods hasn’t really been in the news much since he got hurt in a car crash in early 2021. Why bring him up? What’s with the lift thing? I even googled “Tiger Woods in lift” to make sure I hadn’t missed some kind of obvious cultural reference but the first result was Reason’s column, which didn’t really help.

Sorry. Next bit.

“Here is a man, perhaps not a particularly noble one, who has broken the rules and then been crushed by the machinery of the state.”

Here’s another way to write that, in a way that reads less like The Odyssey by way of Google Translate and more closely resembles reality:

“Novak Djokovic is an enormously rich and extremely famous tennis player, who intentionally broke Australian law, by refusing a vaccination that Australia requires before anyone can enter the country. He perhaps thought his riches and fame would mean he didn’t have to follow the law. In a notable break with Australian tradition, this didn’t happen. He wasn’t allowed to play tennis and had to go home.”

That isn’t being “crushed by the machinery of the state;” it’s a minor inconvenience1 — one that could have been easily avoided by getting a vaccine like nearly 4 billion other people have. Do you know what is being crushed by the machinery of the state? What Australia does to refugees, who, despite Australian government bluster, are legally entitled to seek asylum. Some have been kept in indefinite detention for years, in flagrant violation of both international treaties and Australia’s own human rights legislation.

Astonishingly, and despite asylum-seeker advocates’ desperate attempts to use the Djokovic affair to highlight refugee plight, these actual examples of real government oppression are mentioned nowhere in the column. Instead, it’s about the self-inflicted inconvenience suffered by a tennis player, as it applies to Mark Reason.

Okay. Next bit.

See, it’s this kind of thing that makes me think no subeditor ever got near this column, because not only is that paragraph a dense, indigestible word-salad, the reference is obscure in the extreme. Trust me, no reader knows or cares about a “famous editorial headline,” particularly not one that you “referenced last week,” which was last any kind of famous headline in 1967, and is actually a quote from 18th century poet Alexander Pope! What the fuck? Is this even real? What are journalists?

Seriously – why? Is that bit just a billboard for your Cambridge education or is it supposed to be a joke? If so, I’ve got a comedy writing tip: your audience has to know broadly what the hell you’re on about, and the Venn diagram of rugby aficionados who read British newspaper editorials in the mid-60s and who are also Alexander Pope enthusiasts is three almost entirely separate circles.

Right. How far am I through this thing? Less than a quarter? Oh for Christ’s sake.

Reason now draws a very long bow to connect Djokovic’s self-own with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards getting arrested for drug offenses. Oh good, is this article going to morph into a well-reasoned attack on the unjust and wildly counter-productive War on Drugs?

No.

There’s a point here, which Reason comprehensively fails to make: you could convincingly argue both that Australia is poorly governed at the federal level, as evidenced by its colossal failure on Covid-19, and also that the arbitrary power granted to its ministers is often unjustly wielded, as in the case of indefinitely detained refugees and asylum seekers. But having set up what could be a devastating serve, Reason opts to just kind of lob it into the net. See, we can all do sports metaphors, because as it turns out, it’s very very easy.

Again, there is an argument to be made here — about the perpetual tussle between rights and responsibilities, choice and consequence — and it just doesn’t happen. Instead Reason falls back on a paraphrase of the trite “I disagree with your views but I defend your right to hold them” cliché that doesn’t, in its fresh context, make any sense. Here’s my paraphrase: “I disagree with my alcoholic great-uncle’s views about drunk driving, but I support 100 percent his right to hold them.” So fucking what? My hypothetical great-uncle can have all the odious extra-legal opinions he wants, up until the point he drinks a fifth of vodka and dares himself to drive. Djokovic’s views aren’t the point. The point is he knowingly broke the law and then suffered the extremely minor consequence of not being able to play tennis.

You can see this as draconian if you like, but it’s kind of just how the rule of law works. When Australia offers endless examples of extraordinary legal cruelty to choose from, including everything from the genocide of Aboriginal nations to the indefinite detention of asylum-seekers, Djokovic’s deportation seems a really dull hill to die on.

Next.

Here is an actual image of me, reading that paragraph:

Let’s break it down:

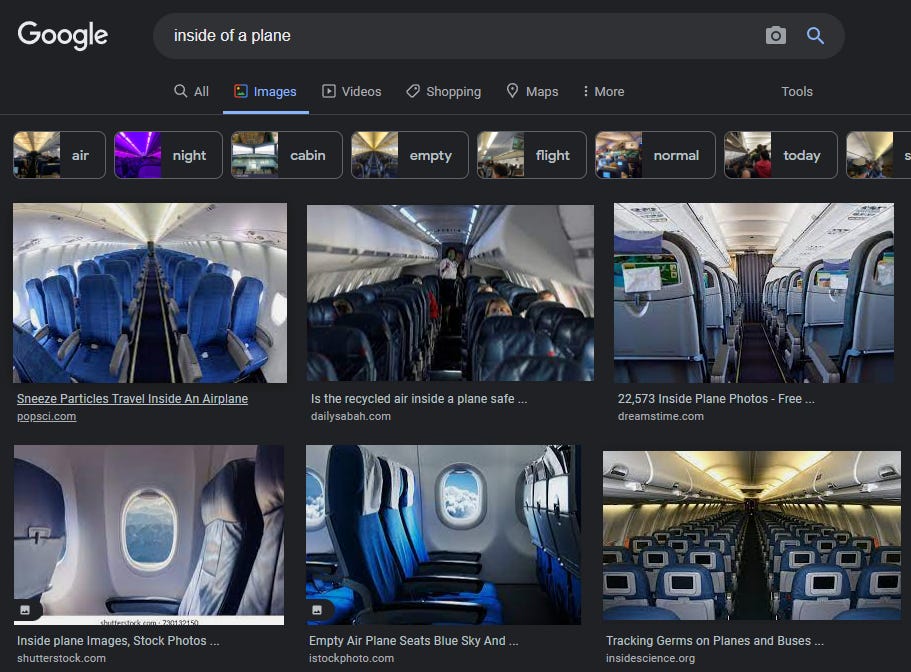

The people on our flight were put on two buses and driven for three hours to Rotorua

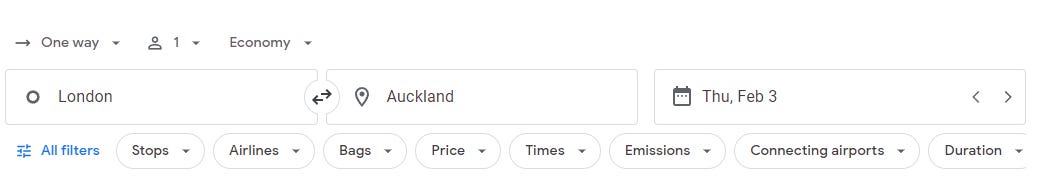

Time for some journalism! I wonder how long it takes to fly from the UK to New Zealand?

So it’s about…. an entire day? With the same people?

This I thought was crazy. There was a clear risk of contagion by putting so many people in so small a space for so long.

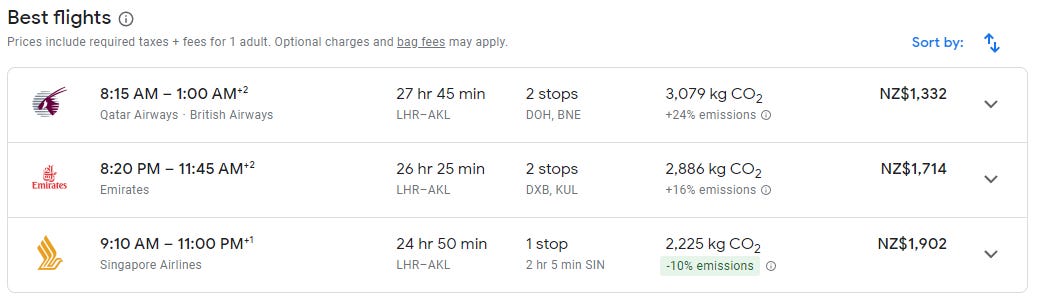

So small a space? Time for more journalism! I wonder what the inside of a plane looks like?

Right, so now we’ve established that a plane is sort of like a bus, but for the sky, and that to take one from the UK to New Zealand it will take about 24 hours.

So why, Mark Reason, you desperately ironically-named man, why, in the name of God would it matter spending three additional hours on a bus alongside the same people you just spent a full day with in a tiny metal tube?

This is what it looks like when someone who’s spent a life largely free of real inconvenience encounters the wrong side of authority for the first time. The same sort of person who’d probably tend to wax lyrical about the noble duty and service of the military is suddenly sneering at some poor guy because — as is often the case with soldiers — he is a young person. If you’re white and male in New Zealand (like Mark and I both appear to be), you occupy an extremely privileged position in which society is still mostly arranged for your benefit. Cops are friendly, drug offenses get diversion, and so on. No doubt a slight shift in this perspective can be mildly traumatising.

On this point, I feel extremely sorry for Mark. New Zealand’s MIQ system has helped protect the country from the worst ravages of Covid-19 for two years, but it’s also been punitively unfair and cruel to those who want to travel home to be with unwell or dying loved ones, even as exceptions are carved out for entertainers and celebrities. So why isn’t the column more about this extremely relevant fact, one that’s persistently misunderstood by the New Zealanders who reflexively defend MIQ and its many failings? I understand it might be hard to write about, but all this blather about Djokovic, all the misapplied fury at the Australian legal system, the sneering, the impatience with inconvenience in the midst of a globe-spanning emergency that’s killed (at minimum!) over five million people — it undoes any real point Reason might have had.

This is the problem with opinion writing in New Zealand media in a very neat package: at the end of the day, a lot is just ranting2. Often enough, there’s an argument somewhere in the rant, but it’s usually only unearthed after generous excavation, and the disposal of a bunch of ill-formed or misinforming slush along the way. It could be so much better.

Onward.

Well, there goes my sympathy. Apart from the jarring change in voice — Reason swerves from first-person to second-person perspective to address the reader directly, something not done in the rest of the column — we’ve got the near-inevitable crux of the article, the pinecone-tier argument that pie-eyed NZ opinion writers seem to be incapable of not making.

He wants us to “move on from that fear.” Yup, it’s just another sermon about learning to live with the virus.

For fuck’s ever-loving sake.

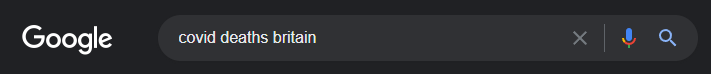

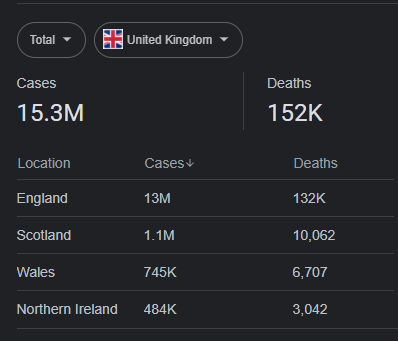

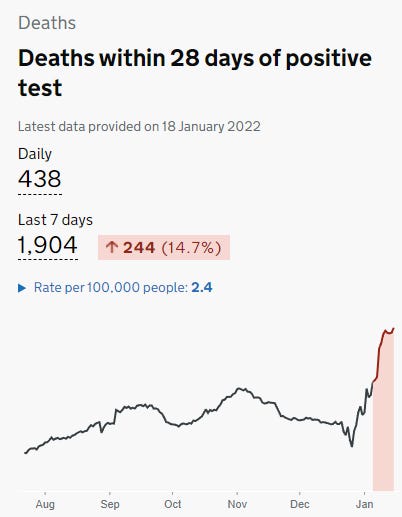

The thing about these learn-to-live-with-the-virus bros — I’m just going to call them Vibros, for short — is that “learn to live with the virus” is mostly shorthand for “let it rip.” Actually learning to live with the virus is a spectrum of deliberate, considered public policy choices, which span everything from what New Zealand is currently doing (mask mandates, mass vaccination, multiple other public health interventions, which have kept infection and death to an extraordinary minimum compared to nearly everywhere else in the world) to what the UK is currently doing (nine tenths of fuck all.) In fact, let’s do another journalism to see how they’re going over there:

hmmmm It’d seem that the UK hasn’t so much learned to live with the virus as it has blundered into how to die with it. You’d think it self-evident that actually learning to live with the virus would involve people still being alive. But the Vibros on the media-political axis urge us to throw open our borders to Omicron (and all past and future viral variants) while nebulously “looking after the vulnerable.” This is always, always shorthand for either locking up the disabled, elderly and immunocompromised forever, or just letting them take their chances, while the rest of us (and it’s always assumed that the vulnerable aren’t part of “us”) get on with it.

Opposition to this nakedly eugenicist worldview is mischaracterised by Vibros as “fear” which “we” must “get over.” Until very recently, we used to hear a lot more about doing this for the sake of “the economy” — a catch-all term that has little to do with the classical definition of the word and instead means everything from “the bank accounts of the rich” to “my freedom to cough to my heart’s content in a crowded theatre.” However, Australia’s sudden realisation that letting ultracontagious, debilitating diseases run rampant is actually worse for the economy than public health restrictions seems to have dismissed that school of thought, at least for a little while.

But let us return to Reason. We’re in the home stretch now:

It may not surprise you to learn that this account of events comes not from reality, but from Mark’s keyboard. In fact, he’s got it backwards. The UK’s public health experts, accurately forecasting Omicron’s catastrophic impact, proposed a lockdown. The Government said no. Here’s how that’s going:

Of course, thousands of people dying every week is much less bad than public health restrictions, according to Mark’s good mate, an NHS “chest surgeon.”

“I am a rule follower.” Not only is this a glaring red flag on a Tinder profile, it really sums it all up: you’re all about the rules, until the rules — for possibly the first time ever — impinge on you, and then suddenly you’re taking to the streets, fighting for your God-given British right to be elbow-deep in pulmonary embolisms.

Mercifully, we’re now at the final paragraph of this turgid, pontificating waste of prose. Well, we are when it comes to Reason’s piece, anyway. Mine still has a few to go.

Oh that’s nice, Mark. It’s the famous British class on full display. Having spent most of your piece spitting in the eye of everything public health personnel are working for, you still take the time to thank them at the end. You really are a nice guy after all. Kia ora. The end!

Well, apart from one last lol, courtesy of Stuff’s donation exhortation:

This makes me wonder. Perhaps I’ve been unfair – Mark Reason is out of his lane, writing about public health. When he writes about his actual purview, sports, is it any good?

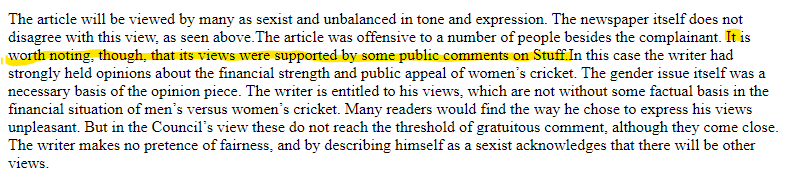

Of course, Mark’s sexist diatribe against women in cricket was referred to the Media Council, and of course — because the Media Council’s code of conduct and rulings are rigged to allow opinion writers to perpetuate cruel, damaging, false stereotypes to their heart’s content — they dismissed the complaint in a piece of reasoning that would be hilarious if it wasn’t so goddamn grim.

Galaxy brain take: “Bigots made comments supporting our writer’s bigoted commentary, therefore it’s not bigoted!” So there we have it. A writer with bad takes on sport is also producing bad takes on current events. Nothing new to see here, tale as old as time, news at 11. But just because it’s always happened doesn’t mean it always should.

So the media doesn’t require you to be qualified to write about Covid. Imagine if that applied to other topics, like sport. Imagine if they gave me a rugby column in the paper, despite barely knowing the rules.

“Shocking performance. They aren’t grabbing the ball nearly enough!”

— Lou (@louhalfwaythere) 9:00 PM ∙ Jan 19, 2022

There really aren’t any excuses left. If a global pandemic doesn’t give the news media pause about how the lassitude given to opinion creates a loophole for lies, nothing will. Misinformation is running rampant, and there’s never been a more urgent need for truth in story-telling. Explanatory or analytical journalism, including opinion, can and should be done well. When there’s no lack of evidence for just how good it can be, why should audiences settle for less?

And now, a word from me.

I don’t want to keep doing this.

A few months ago I sent out an overwrought, overlong jeremiad about bad Covid takes in the NZ media and the response was terrifyingly positive. I got comments, messages and emails from a truly surprising number of people3. What was most gratifying was the number of journalists who reached out to me, off the record, to tell me I was on the right track, and to share their own frustrations with opinionists — who they see as devaluing their work and bringing media into disrepute. Still more surprising was the number of people who not only signed up to the newsletter but subscribed, with real actual cash money. The Project came calling, and their kind producer spent much too long with me coaxing my interminable nervous rambling into a useable soundbite. When it aired I asked my wife to watch it before I could look at it.

Naturally, my response to this outpouring of support was to go dark for a few months. I’m a newish dad with a reasonably demanding day job, and on top of this, success has always spooked me. It means attention, and its dark shadow, obligation. I’m uncomfortable with both.

What’s more, I’m very aware of the irony, and the folly, of ranting about ranting. Mass media opinion pages and talk radio have always provided a safe space for cruel, counter-factual mendacity, and publicly complaining about this isn’t too far off “old man shouts at clouds.” The media will keep giving me material until I die or the oceans boil, whichever comes first. But I think I’d get very sick of it, and so would you.

So what I’m saying is: while I would still like to do media criticism when I think it’s worth the effort — if nothing else, it’s cathartic — I’d also like to expand the scope of this newsletter to be about other stuff as well. If you’re keen, this means you’d hear from me a bit more often.

For me, it also resurrects a long-buried dream. After a bunch of you reacted to the Fifth Columnists by clicking on the “subscribe” button I’d put up on a whim, I did a bit of maths, and with around 1000 paying subscribers (a mere 0.0000125% of the world population, I tell myself to make the number seem less big) I’d be well on my way to actually feeding the kid and paying the mortgage with this thing. And that seems… almost achievable! So maybe I should actually pursue it. Ultimately, you’ll make the decision for me.

For the next newsletter, I’d like to write about some possible solutions to unethical or morally dubious media conduct. I’ve got a few ideas and I’d love to hear yours. And if there is something else you’d like to see me write about, let me know.

Thanks for reading. Here’s the fiscal support button:

Here’s one that helps you win friends and influence people4:

And here’s a button that makes virtue-signalling and argument-starting with friends, family and strangers even easier than it already is:

-

Of course, it’s less of an inconvenience for Australia’s admittedly terrible government, which is probably happy to draw attention from the way that they just kind of invited an ultracontagious virus to run rampant across the country, destroying businesses, sickening hundreds of thousands, and — most damningly — killing vulnerable people. ↩

-

Yes, this is a rant about ranting. It’s like rain on your wedding day. ↩

-

Please bear in mind that any number much larger than zero would have surprised me, so take my hyperbole with a pinch of salt. ↩

-

Lies ↩

-

The Fifth Columnists

This is a long one, so…

Let’s begin with a series of interesting facts.

-

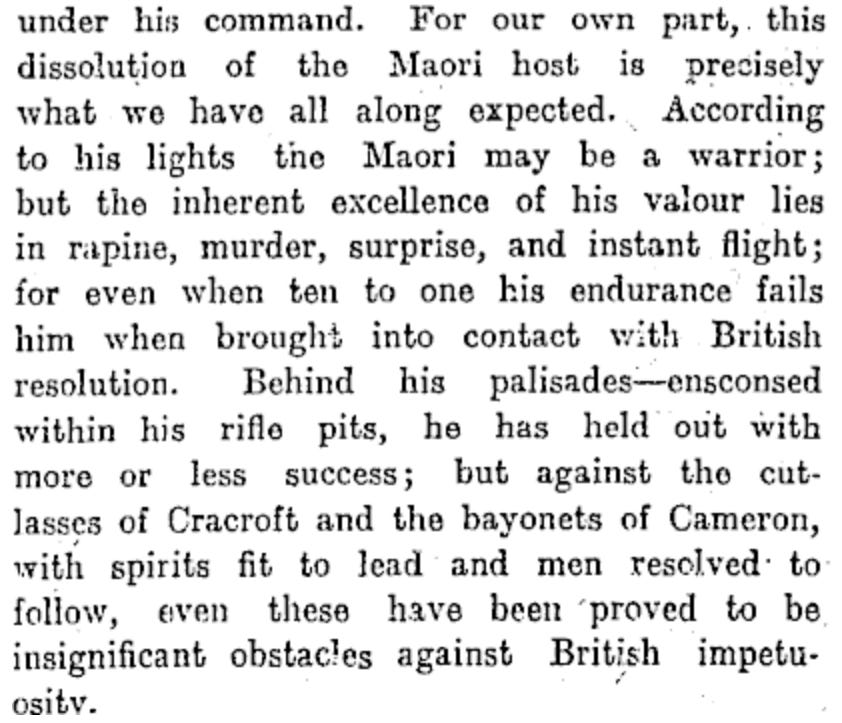

Some extracts from the first-ever editorial of the New Zealand Herald, November 13, 1863, which is very concerned with the health of the business community. (Content warning: racism, ethnic cleansing, purple prose.)

-

The New Zealand Herald Twitter account, October 3 (Mean Girls Day) 2021.

-

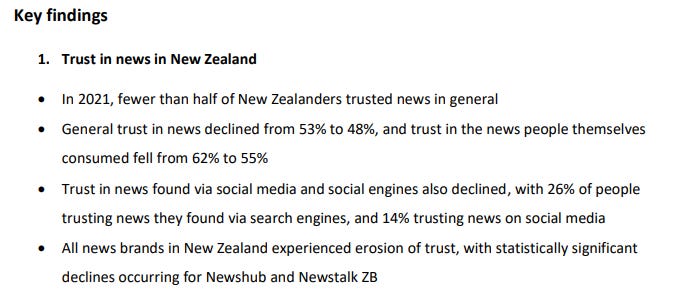

An extract from the “Trust in news in New Zealand 2021” paper published by AUT, April 29, 2021.

-

Interesting.

So here we are: 2021, year two of a global pandemic that has killed, at minimum, 4.5 million people — the rough equivalent of New Zealand’s population being all but wiped out. To date, New Zealand has had one of the most comprehensive, successful and popular public health responses in the world, and some truly good luck. But the ultra-contagious Delta variant has now snuck past our defences, and our largest city and several regions are in Level 3 lockdown.

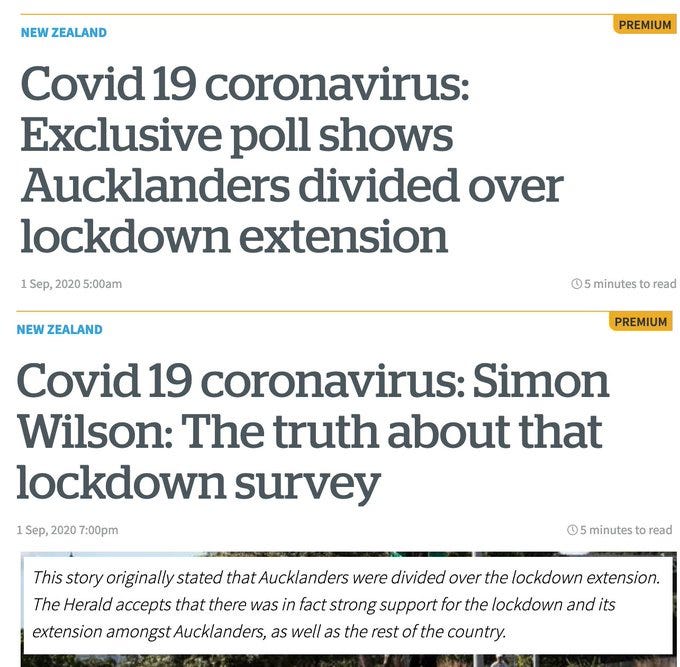

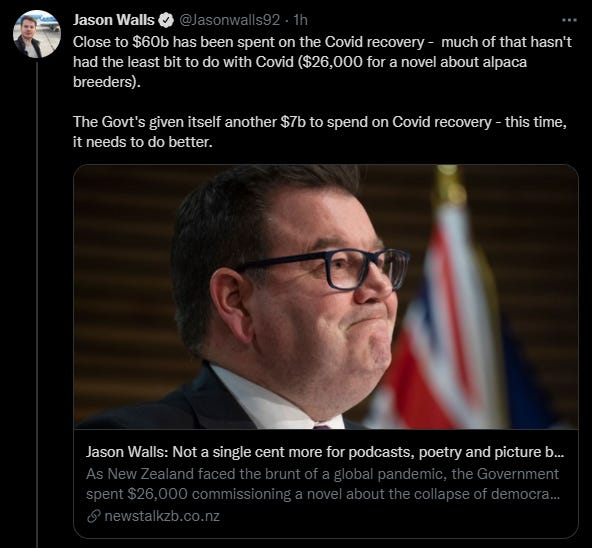

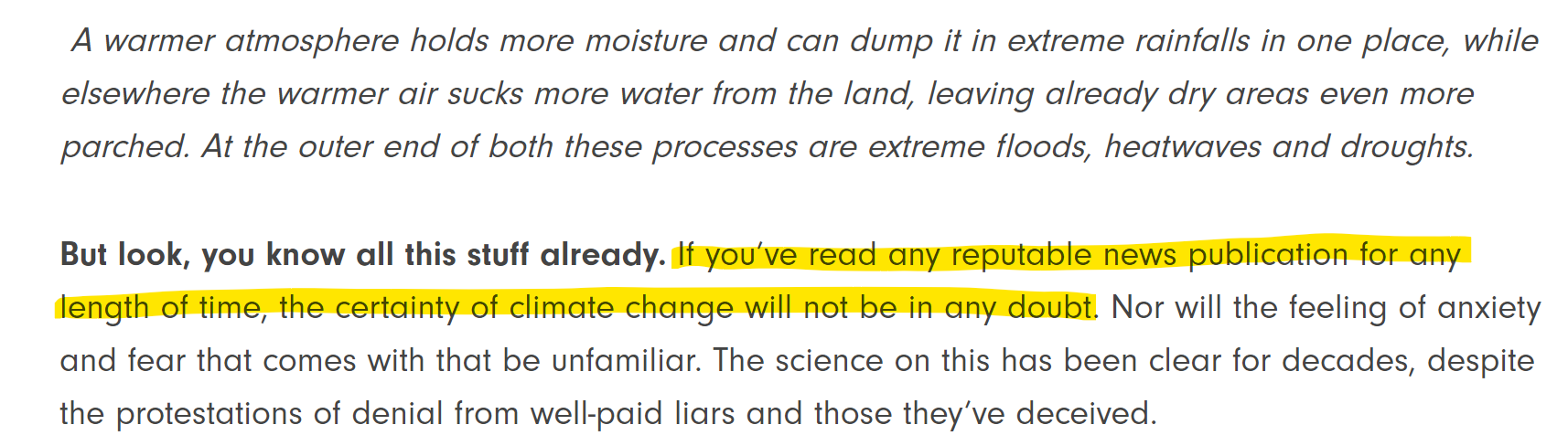

And sizeable chunks of the New Zealand news media, as they have done since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, are undermining the public health response. Multiple news publishers in NZ have intentionally and consistently platformed the worst takes and advocated for the worst possible courses of action that, if followed, would have left thousands, or tens of thousands, dead.

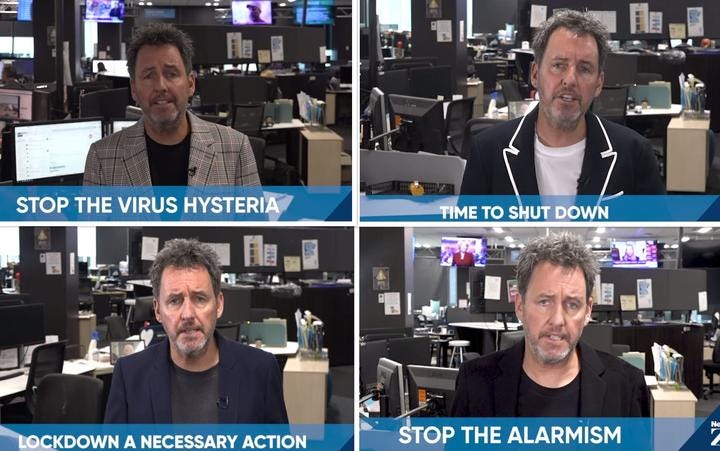

This undermining, in the guise of opinion journalism, has been led by NZME’s stable, including the New Zealand Herald and Newstalk ZB, which are these days essentially the same publication. A lot of NZME’s undermining comes, incredibly, from two actual married couples, who between them comprise what is possibly the country’s largest opinion media platform. Mike Hosking, Kate Hawkesby, Barry Soper, and Heather du Plessis-Allan.

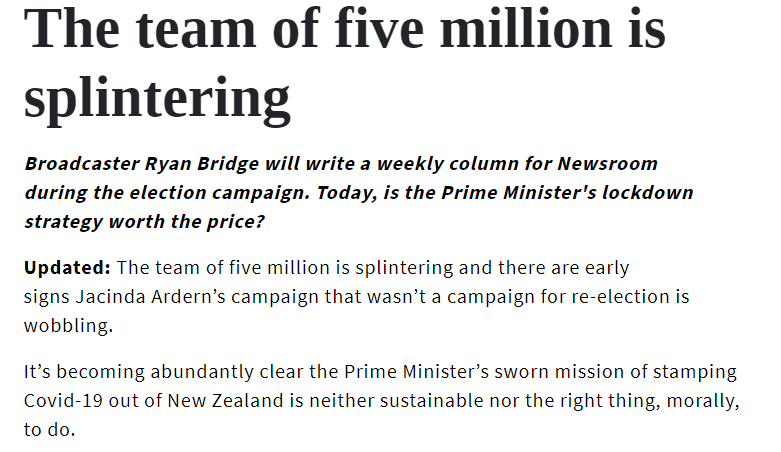

But wait, there’s more. There’s the Herald’s John Roughan. There’s Stuff’s Mike Yardley. There’s Newshub’s Ryan Bridge, who is for some reason gifted another platform on top of his regular radio and TV shows at the usually-excellent Newsroom.1 There are many more — too many to list, really. It’s a roll-call of some of New Zealand’s most high-profile people, all of whom have access to vast media platforms to spread their opinions, unhindered by any kind of health expertise, and unchecked by any sense of responsibility given the gravity of the present moment.

It’s important to note that relatively little of this attack on an unprecedented public health response has taken place in the medium of news reporting. While it’s often sensationalized, news journalism has mostly been consistent with the ethical requirement to report the truth without fear or favour. News journalists aren’t the ones at fault here. Most have difficult, poorly-paid, and often thankless jobs, which have been made much harder by newsroom downsizing and lack of resourcing, combined with high workloads and the taxing requirements of reporting on a global pandemic.

Instead, the undermining has taken place under the banner of the media’s opinion columnists and broadcast hosts; the mouthpieces for what publishers and their advertisers actually think. Their attack has been endless. Because the word “pundit” implies expertise, which these people typically don’t have, I’m going to lump them all together in a category I’ll call “opinionists.” It’ll save me typing “opinion columnists and broadcast hosts and ex-politicians” over and over again.

I’m not lacking for examples of this extraordinary attack on public health. Because I am apparently a masochist, I asked NZ Twitter to crowdsource some of the worst takes they’ve seen. Even by the high (by which I mean low) standards set by the media over the course of the pandemic, there are some astonishing howlers in there.

Let’s have a look at some of what’s been said, shall we?

“The public health response preventing mass death is morally wrong”

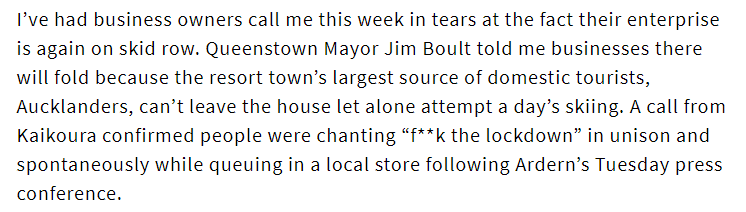

Sometimes they really do just come right out and say it. Here’s Ryan Bridge, August 15, 2020.

This is such a neat summary of the problem with these opinions that I could almost stop here. Here’s the issue: if something – in this case, lockdown – isn’t “the right thing, morally, to do,” then it’s obviously justifiable for members of the public not to engage in it. Without very high rates of vaccination, preventing mass death from Covid-19 and its variants requires an understanding shared by millions of citizens that allowing themselves to be locked down to to avoid spreading a deadly virus is morally the right thing to do. Bridge is here explicitly undermining that principle. Why?

It’s for the same reason nearly every other opinion-monger has cited in their endlessly repeated concern-trolling: “Won’t somebody please think of the corporations?”

Let’s be clear: having a business die is difficult and heart-breaking. You know what’s worse? Actually dying. What’s also worse? Having loved ones die. And worse again? Having thousands of people, all of whom are loved ones to someone, die.

A business that dies can be reborn. A person that dies cannot. It’s as simple as that. This fact — and the fact that nations choosing “we must learn to live with the virus” prior to the advent of the Covid vaccines almost immediately began to suffer catastrophic mass death — has been consistently ignored by the media’s hot-take machine.

Elimination is impossible and doesn’t work, if you ignore the 18 months where it was possible and worked

For a great example of this trope, let’s hear from Heather du Plessis-Allan’s husband and media veteran of most of the last century, Barry Soper, on 21 September 2021.

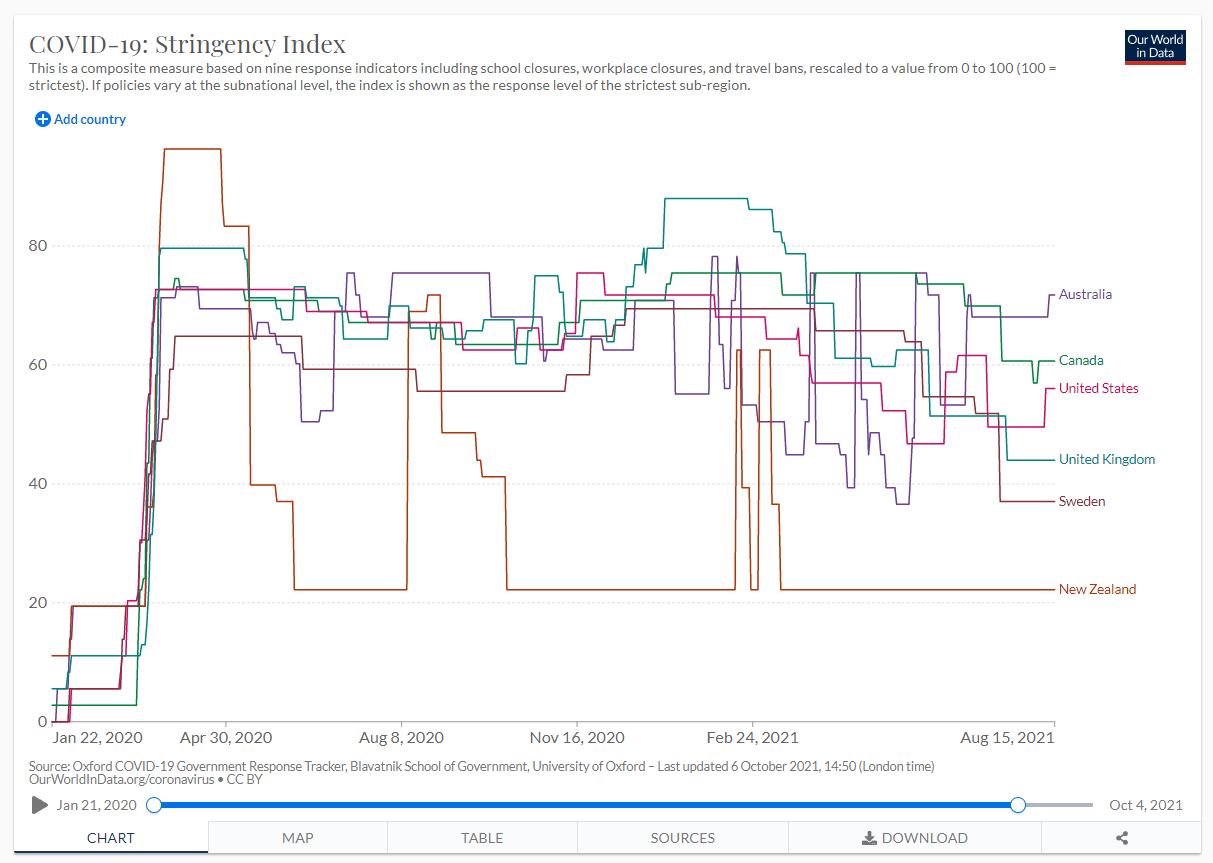

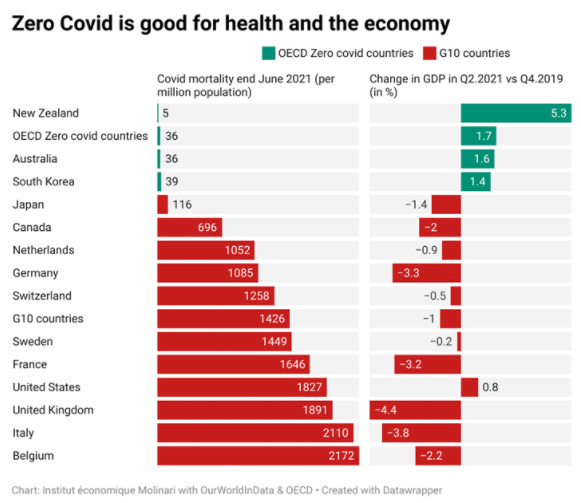

That’d be the same “impossible elimination strategy” that saw better outcomes for NZ than nearly every other OECD nation for 18 solid months, Barry, but go off. Except for those 18 months, it was impossible. To make the point, let’s use a tool that, somehow, opinionists who decry the success of NZ’s approach seem never to have seen: The Covid-19 Stringency Index.

As we can see from the index, from near the start of the pandemic up until the beginning of the Delta lockdown on August 15, New Zealanders enjoyed an extraordinary measure of freedom compared to other comparable nations, including essentially all of the OECD.

Of course, that’s currently a thing of the past; we’re back in lockdown. But, according to the opinionists, that’s because of “the spin.”

Barry continues:

This isn’t “the spin,” Barry. We know, from both modelling and actual live examples in other countries, exactly how fast the Delta strain of Covid-19 spreads in populations that aren’t taking precautions. But you have a keyboard that apparently knows better than both expertise and evidence, so by all means carry on.

A bizarre inability to recognize the scale of the catastrophe in other countries compared to NZ

The falsehoods most promulgated by the opinionists are lies of omission. Ignoring the extraordinary scale of the Covid-19 tragedy in nations like the US and the UK is the norm. Instead, we’re told to be jealous, because other countries are “opening up.” A country is cherry-picked as an example — in the early days of the pandemic it was Sweden, and then when it became clear that Sweden’s approach was catastrophic, the opinionists happily moved the goalpoasts to another nation. The current favourite is Singapore, which is currently (and inconveniently, for the pundits) oscillating between loosening and tightening restrictions, so we can anticipate a new favourite will be chosen soon.

Here’s HDPA, on 22 August 2021.

It’d be difficult to find anyone who’s ever seriously suggested that we should keep our borders closed forever, but that hasn’t stopped the people who get paid to make this shit up. It’s an old tune, done to death. Here’s HDPA, back on 23 April, 2020, by which time the scale of the catastrophe unfolding in other countries was well known:

“Just a wee bit!” To showcase how little this messaging has changed since the early days of the pandemic, here’s Kate Hawkesby on 23 August, 2021.

Of course, the “rest of the world” isn’t “open;” as anyone can see from the Stringency Index, most comparable countries are still labouring under significant restrictions, which can and do ratchet up higher when Covid cases threaten to overwhelm the health system. But, undeterred by reality, they carry on. Here’s Paul Henry, with opinions on his Palm Springs, California bubble:

That’s nice, Paul. The only fly in that ointment is the 5,055 deaths in Riverside County from approximately 367,000 Covid-19 cases, a death rate of around 1.3 percent. Those people will be unable to get on with their lives, by virtue of being dead. What’s more, Riverside County (which has a lower full vaccination rate than NZ, at just 49 percent to NZ’s 55 percent) is at the time of writing still grappling with a fresh wave of Covid restrictions and deaths (130 have died over the last two weeks), and the CDC currently recommends that even vaccinated persons wear masks when out of their homes. That’s not “moving on,” that’s the reality of life in a pandemic that is still raging.

“Cutting through the spin” by, uh, lying

“We have lost our marbles when it comes to health matters in this country. We are more gripped by whether people end up in hospital with Covid… when there are people dying of cancer that couldn’t be treated and haven’t been… The Cancer Control Agency was yesterday talking about how half of new cancer cases are going to be missed.”

That’s Mike Hosking with the alarming news that cancer diagnoses and treatments would be missed because of Covid lockdowns, a claim that was echoed by the Leader of the Opposition, Judith Collins. The only problem with this is that it’s not true. Cancer diagnosis and treatments do not appear to be declining at all. In fact, they’re keeping pace with historical rates – or at least they are in NZ. You know what is interfering with cancer treatment in other countries? Hospitals being overwhelmed by Covid-19 patients.

Moving on, here’s Heather du Plessis-Allan with the claim that the Government is trying to “gaslight” the public:

“Trying to gaslight us into believing we’re still going to reach zero” isn’t true. For clarity, here’s what Bloomfield actually said about elimination, over a year ago, on April 20, 2020.