Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Newsletter

Fellas, are you OK?

Gidday Cynics,

We’re a few months in to this project now and I’ve noticed something interesting: the most engaged subscribers here aren’t men.

There’s nothing wrong with this. But it’s definitely not what I expected. I figured a newsletter that tackles big themes like “increased productivity” and “how many pull-ups I can do” would attract mostly dudes. It makes me interested to see how people receive this week’s topic — something that’s been bugging me for ages now.

Fellas, are you OK?

Please note: the following contains discussion of self-harm and suicide.

In many ways this question is already answered. Men, collectively, are not OK. It’s been a while since I browsed the statistics, so I’ve been able to react with fresh horror: By a staggering proportion, men commit most crime, including the worst crimes such as violent sexual assaults and murder. Here are the New Zealand police proceedings demographic data, neatly stripped of their unfathomable human tragedy and rendered into graphs:

This chart, annoyingly, did not come with a labelled Y axis, but you can safely assume that up = more. Men also kill themselves at an awful rate: in New Zealand, the suicide rate for men is around four times that of women — a statistic that seems to hold true for other countries. I know there are caveats to consider here, but the sheer discrepancy is shocking.

Because it’s well-known that men are not OK, and because the causes and circumstances of this malaise are complex, men’s wellness has long been easy fodder for grifters. The current cure, touted by a seemingly endless parade of (usually) male griftfluencers, is that men have become soft and simply need to, uh, man up.

As far as science can tell, this isn’t true. The shittier traits associated with masculinity — often called “toxic masculinity” — aren’t good for men’s mental health, according to a comprehensive meta-analysis published in 2016. As the Smithsonian Magazine reports:

“Sexism isn’t just a social injustice,” says Y. Joel Wong, a psychologist at Indiana University Bloomington and the study’s lead author. “It may even be potentially problematic for mental health”—men’s mental health, that is.

But facts have never got in the way of this terrible story, and the people telling it are making out like bandits.

Tucker Carlson is famous for a lot of things, most recently for being sacked by Fox News. But before that, there was… whatever this is:

Tucker’s special The End of Men, feat. testicle tanning, men milking cows, shirtless dudes wrasslin’ each other, and all sorts of other weird shit is classic Fox infotainment; baiting both concerned conservatives and easily-enraged liberals with equal aplomb. As usual, there’s a core of truth to this bullshit pearl; testosterone levels in men are dropping over time, at a population level, and no-one knows exactly why.1 There are also plenty of people for whom careful monitoring of testosterone is part of necessary health or gender-affirming care. My intention is not to have a go at them, but to point out that the solutions articulated by right-wing media personalities and manosphere grifluencers are intended to stoke anxiety in people whose testosterone is probably perfectly fine.2 But wait, there’s more. Parker Molloy, author of the excellent Substack newsletter This Present Age, has an explainer at Rolling Stone:

As ridiculous and easily mocked as these videos are, they represent an ascendant ideology on the right and an extension of Carlson’s long-standing belief that there is a war on masculinity that threatens to destroy society itself. This theme of social collapse is a mainstay of Carlson’s Fox News show, with immigration, LGBTQ rights, and the battles against racism and sexism are all framed as threats that must be beaten back to maintain Carlson’s preferred patriarchal social order. In short, the video’s not actually about the benefits of sunshine on one’s scrotum at all.

More recently, in February of 2023, Vogue magazine put singer Rhianna on the cover, together with her husband A$AP Rocky and nine-month-old son.

Naturally, completely normal men immediately drew diagrams all over it.

Normally I credit images to the creator, but not this time. Note that the baby has a “happy face,” apparently a notorious sign of a weak father. This “green line” stuff, which was briefly the subject of a Tik-Tok trend too painful to discuss at length (but which is easily Googleable if you want to induce a headache) was the creation of an incel-adjacent manosphere Twitter guy with 175,000 followers. Clicking on a few links or suggested follows — thank you, socially destructive algorithms — quickly turns into a bottomless shitmine. Here’s just one of the nuggets from near the top that shows exactly where these people’s minds are at:

What the fuck? And here’s what gets me about this stuff, all these keyboard worriers publicly bemoaning the state of men: it’s not very manly, is it?

Obviously, I don’t think caring about the state of the world makes you unmanly or in any other way unworthy. If I did, I’d have to stop writing. But this overwhelming preoccupation with a lack of masculinity, particularly among the Profoundly Online Dudes that are the vanguard of our endless cultural wars, just seems to me to be kind of weak. Think of the state of the discourse around “alphas” and “betas,” which started as a misunderstanding of how wolves work3 and has since been carefully nurtured by incels and other manosphere denizens. And as long as we’re appealing to the animal kingdom for examples of how people should behave, which these people always do, let’s use it to dismiss the notion that strength and nurturing fatherhood are mutually exclusive. Silverback gorillas are quite capable of lazily separating a human’s arms from its body but they play with and cuddle their babies all the time.4

The content peddled by these belligerent yet fretful male influencers is, at best, total pseudoscience, but the fact remains but a sizeable proportion of the male population seems to both care about this stuff and take it seriously. To which I say: why? If alphas and betas existed (they don’t) the only people who’d devote any time to worrying about being alpha would be betas. And, weirdly, that’s exactly what a lot of these guys do.

I’ll change the tone of my address a bit here: if you, or anyone you know, is caught up in this stuff I think there’s a relatively easy out — or, if you want to put it that way, a shortcut to alpha-dom.

Stop caring about it.

Seriously. Stop giving a shit about whether you’re manly enough, because fretting about being manly is not manly. By way of proof, I’ve got exactly what every griftfluencer telling you to care about the state of your gonads so they can sell you powders or red-light machines has: an appeal to ancient wisdom. Tell me, have you heard of… the Spartans?

Well, they were an ancient society of Greek warriors and blah blah blah. You’ve all seen or heard of 300 and the associated memes and learning opportunities. Did you know that there weren’t just 300 Spartans at Thermopylae there were actually thousands of Greeks ugh, I’ll spare you the rest. But there’s one thing that’s well worth remembering about the Spartans, and is easily the thing I find most endearing about them: they were laconic.

Spartan children, for whom education was compulsory, were taught from an early age to be laconic in their speech. Essentially, it’s being concise to excess.5 This example is often given:

Persian commander: “Our arrows will blot out the sun!”

Spartan: “Then we will fight in the shade.”

According to a wildly funny Wikipedia entry, this might actually have happened. It certainly seems to have been in keeping with the sort of thing Spartans actually said.6

Back to the point: while Spartans obviously cared very much about being masculine, I can’t imagine that these bloke’s blokes would have been even mildly interested in drawing diagrams explaining how a rich and famous man who performed the actions necessary to produce a child with someone as infamously hot as Rhianna is actually a cuckold. If it’s masculinity you’re looking to cultivate, then there are plenty of methods I’d argue are non-toxic, more fun, more accessible, and much better for you than worrying about it. Here is a short list, pulled entirely from the top of my head:

- Exercise (if your arms work, pullups are free and satisfyingly difficult yet easy to improve at)

- Learning a manly art of some kind. Go find a woodworking class, or learn to paint. Build a table or something.

- Channel the masculine urge to protect and serve into learning about and dealing with actual problems, like climate change, instead of pretend ones like how much sun your balls do or don’t get

- Make a good cup of tea (there’s an art to it)

- Learn an instrument: you can get an OK second-hand guitar for $50 and tablature can be found for free online

- Get in the sea. Seriously, ocean swimming is good for your soul

- Get a bunch of rocks or other small objects and throw them into a bucket; my flatmate and I got hours of entertainment from doing this when I was at University and a literal bucket of rocks is leagues smarter than Andrew Tate

- Touch grass. Just go for a goddamn walk

It’s not that I think any of the above should be the exclusive province of men; it’s just that I think there are lots of useful and manly things that dudes can do on the cheap without needing to spend their time worrying about how manly they are. By all means, go to the gym. Shoot arrows at targets. Acquire a collection of flannel shirts. Grow a beard. Do other forms of male-gender-affirming self-care. Just get off the goddamn internet for a bit and stop worrying about whether men are leaning correctly or whether a given celebrity is a simp or the state of other blokes’ nuts. Because, if that’s something you’re giving undue attention to, you’re being grifted. Here’s Molloy again:

By presenting men insecure about their masculinity with an enemy in need of domination, fascist-friendly media personalities can pull their audience to the right. This is what’s currently happening with the moral panic about “grooming” playing out across right-wing media and being implemented as policy by right-wing politicians. A recent video of the crowd at a Trump rally chanting “Save our kids“ shows just how successful this type of messaging continues to be, consequences be damned. The goal is to not only halt social progress, but to reverse it by painting pro-equality messages as part of nefarious schemes to undermine Western civilization.

If you’re a guy, and you’ve been caught up in anything like what I’ve described — please, take a step back, and think about how weird it all is. Whatever positive masculinity is, all that shit is its opposite. The world needs good men. Go be one.

I’m about to take my own advice and go for a walk, but to keep you on top of my own self-improvement experiment, I managed to do a colossal eight consecutive pull-ups the other day, and there’s a new painting did. Even better, this one has a video to go with it. Go on, lick and subscrub. I’ll see you in the comments!

@tworuruCan I fix this Pikango painting in Breath of the Wild? #botw #breathofthewild #legendofzelda #totk #art #fanart #artistsoftiktok #gaming #fyp

Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

No AI was used in the creation of this content.

-

There are a lot of suspected culprits, including plastic pollution — thank you, fossil fuel industry, for this among so many other wonderful gifts — and euphemistic “lifestyle factors,” which may or may not involve too much sitting and scrolling through manosphere nonsense while worrying about testosterone. ↩

-

Out of curiosity, I asked my doctor what my T levels were. Apparently they are very slightly above perfectly normal. Exercise can elevate testosterone, so it’ll be be interesting to check back in a year and see if levels have gone up — but, I have to emphasise, it’s nothing more than interesting. ↩

-

Man, what is it with self-improvement and wolves? ↩

-

Male gorillas also form harems and have testes the size of raisins, so as always, proceed with caution when basing major life decisions on animals that aren’t people. ↩

-

No-one who reads this newsletter is ever going to accuse me of being too concise. ↩

-

This laconic property — brief, blunt, wry, clever — has since been ascribed to the Australian and New Zealand national character. Champion Kiwi comedy export John Clarke said that New Zealanders didn’t really tell jokes but that they did talk very well, and that pretty much sums us up. ↩

Always read the comments?

Gidday Cynics,

It has been a Week. The day job Matrix has me, and while this is definitely cause for celebration — having a job is an increasingly rare privilege these days, plus I actually like what I’m doing and suspect I may be borderline good at it — it has left scant time for newsletters.

So I’m going to do something I’ve wanted to do for a while, and throw over to you, the readers. Although Cynic’s Guide is still just a baby in the newsletter lifecycle, I’m thrilled to have already acquired a brilliant and engaged commenter community. Imagine the comments on typical news website Facebook page, then imagine the opposite. That’s you. Be proud!

So for the rest of this newsletter I’m going to take some of the best reader feedback from the Webworm that kicked off this whole boondoggle as well as the newsletters that I’ve put out since, and give some more in-depth responses.

Let’s start with Michele, one of many readers who offered solid feedback and insight on that first Webworm article.

Michele says:

Yes indeed ‘the fields are ripe unto harvest’ for the opportunistic grifters (who are simply me or you with the volume turned WAY up) to ply their message of hope and validate our distrust of anything we are not.

This is extremely true. A lot of people in the self-improvement space really are just randoms with unwarranted confidence: living embodiments of the Dunning-Kruger effect. Whether or not they deserve the term “grifters” is debatable. I’m pretty sure some are intentionally grifting, but is it worse if they’re amplifying and manipulating people’s dissatisfaction unintentionally?

Emily says:

I’ve always felt like churches, cults, mlm’s, and the self help industry all recruit in a similar fashion. They look for an emotional vulnerability they can lean on, hit it as hard as they can, and then offer you both a solution and a community. The thought of a solution to your problems draws you in, and then the community traps you. It’s hard to pull yourself away from something when it feels like your whole life is wrapped up in it.

Yup. It’s all part of a continuum. I’m pretty sure a lot of my own distrust of cultish self-improvement communities comes from bad religious experiences. Even exercise classes tick that box for me, and for a long time I disliked participating in improv warm-up exercises. Too culty!

Bentia says:

It’s wrong to mock those who are trying to improve themselves but it’s well and good to truly interrogate those who are selling it to us because they are so often, deeply sick themselves… I try to stay away from self improvement for my own sanity since I don’t deal well with failure at all (I don’t even do New Year’s resolutions) I truly believe that the only safe form of self improvement involves therapy with a licensed professional and possibly an actual psychiatrist. There are too many scams out there and too many unwell people who are trying to get better by selling you something that hasn’t even worked for them.

Yes! A lot of people selling self-improvement are deeply fucked up. This speaks to a big part of what I’m trying to do — I want to find self-improvement stuff that isn’t being hawked by people who are themselves doing it to feel less broken, and that’s relatively safe to try doing yourself. Here, like before, there’s a continuum, and people are going to have to find their own comfort. Technically, going for a run is unsafe — you could have a heart attack, or get hit by a car, or be savaged by two wolves1 who aren’t inside you — but it’s rewarding and long-term it’s probably going to be quite good for you.

Karen says:

I have been involved in some of the wellness world a bit and here is how it sometimes goes:

1. You’re very special

2. You’re also fucked

3. Only I can fix you. Give me your money

I have read too many self-help books with that exact plot. It’s too predictable. They need to mix it up a bit.

A. Michelle says:

most of self-improvement pop culture is a grift. I think that monetizing the grift has shifted from books to influencers, the latter actually being *worse* because anyone who likes taking selfies and pointing at invisible pop-up text boxes can do it. It doesn’t need to be accepted by a publisher or go through an editor.

Fucking hell. This is too real and it makes me feel old. I can’t be doing with TikTok, I just can’t. It stresses me out. The app got wind of the fact I’m interested in self-improvement so it keeps trying to hook me on tradwife influencers peddling Christo-fascism and weird Jordan Peterson acolytes trying to sell me the benefits of testicle-tanning and (judging from the adult zits and haunted eyes) steroid use. I just about manage to put my art on YouTube but doing dances while pointing at the blank space where a text box could be while that horrible obnoxiously cheerful robot voice reads out the caption… fuck that all the way to hell. I’ll stick with my text-heavy newsletter like a common ageing millenial troglodyte, thank you very much. Humbug!

Denis says:

Self-improvement was considered to be a vital part of being “successful” in MLM ! We were forcefully encouraged to BUY, read and study books by Zig Ziglar, Eckhart Tolle, Tony Robbins, Dale Carnegie, Robert Kiyosaki (net worth $100 million) – in fact you couldn’t “go core” until you’d bought these books and introduced a certain number of people to the business in one year! Basically “going core” meant you were sucked in by the carrot offered to you – work hard at recruiting and selling for one year with the promise of an afternoon on the Amway super yacht rubbing shoulders with one or two “Diamonds” in the business!

When I was a kid I read Robert Kiyosaki’s Rich Dad, Poor Dad and found it exciting (I was 16) but disquieting. If I remember correctly, it was an cheat sheet for becoming a slum lord. I soured on it completely when I realised that Kiyosaki had become rich by selling a board game called The Cashflow Quadrant about how to become rich. So yeah, spot the grifter.

Jamie says:

I think grift/scam is actual a semi positive term for some of these self help gurus, these people are after far more than just your money. They want to program you, and they’re very open about their objective, they want your money, time, endorsement & your success stories.

Yup. Like so much in our current state of so-called late stage capitalism,2 you and I are not just the customers; we are the product.

JP says:

Second, the unhealthy-ness that comes with people taking self-improvement too far has always facinated me but I don’t see it discussed so openly. I’m frustrated how self exploration and educating yourself in history, philosophy, psychology and spirituality so often bumps up against this unhealthy obsession with someone trying to ‘fix’ you and nothing ever being enough. It’s so healing to see this being talked about. Thank you so much.

Thanks JP! I’m sure there are healthy ways to explore this stuff. I’m convinced self-improvement is a pretty fundamental human impulse and I’m tired of seeing it monopolised by grifters and earning a reputation as garbage.

Kat says:

I feel like your assessment of self-help is quite gendered as you haven’t identified any of the ways parents (mostly mothers) are preyed on and all the ways they could be improving their parenting. I hope that’s included in your longer project 😊

This is true, and a good point. I replied to this comment when Kat wrote it on Webworm, but I wanted to do it again here. I’m looking at the world of self-improvement from my perspective, which is as mid as it is possible to be. I am a married straight white man with a corporate job, approaching the pointy end of my 30s, who has become overly interested in pull-ups. Fortunately, I have friends who identify otherwise and have different perspectives, and some of them have offered to write guest spots. Others have agreed to interviews. I’m looking forward to showing their perspectives here, and if you have expertise you’d like to see shared, I’d love to hear from you.

Some more recent comments! This one popped up just a couple of days ago but I forgot to reply. Linda says:

If you could share some tips on how to get out of bed when the alarm goes off that would be great!

Putting your phone away from your bed is just cruel to your morning self, I can’t do that to poor morning me.

Uhhh. I’ll share what works for me, in order of “sometimes effective” to “100 percent guaranteed effective:”

-

Putting my phone in a different room. Sorry! I do this most nights, and perversely, I find that the antici3 of getting up to see all the exciting messages that have undoubtedly arrived in the wee hours can help yank me out of bed. Then I get up and reply to work emails. Brains are weird.

-

This one is embarrassing, but it works. I pretend I’m a robot. Instead of trying to will myself out of bed, I just watch as my limbs kind of autonomously operate to drag me to the kitchen kettle where I can make coffee. Binary solo.

-

Acquire a child. Having a screaming infant in the house will get you out of bed at any hour of the day or night, repeatedly. I guarantee it. The human brain is hardwired to be unable to shut that sound out.

And, stealing advice from others: you might benefit from more sleep, if that is possible for you, and more exposure to sunlight in the morning. Both can really help.

More comments I forgot to reply to! Amy Smith says:

I once played assassins creed so much during highschool (HSC Trials) that I experienced the Tetris effect and was playing it when I closed my eyes and hearing/hallucinating the eagle scream 😳

Ugh, shut-eye hallucinations after doing the same thing too much during the day can be really intense. It’s happened to me with videogames many times, but the worst ones I ever experienced were when I worked as a beekeeper. I’d shut my eyes and they’d be full of bees.

Here’s one of my favourite comments, from the Two Wolves fakelore article, courtesy of my friend Jackson:

Shaped by late stage tech capitalism we’re being reduced to ‘gramable characters of ourselves with all the gory details almost literally filtered out. All this unfactchecked trite superficial bullshit is easy, it’s a nice story that helpfully neglects the complex’s realms of neuroscience, psychology, and physics (how the fuck do two full grown wolves fit inside a human let alone have enough space to fight?)

Now there’s nothing wrong with having a yarn and spinning a tale — even if it is a bit of a shit one. The problem arises when we’re so bombarded by these simple black/white narratives which just do not stack up with out insanely complex lived experience. They start to make us feel shit. If I could only tame that wolf. Next thing you know your YouTube recommendations are all videos about how to tame wild animals and your Insta ads are all at home surgery kits.

The weird thing is that Seneca kinda foresaw all of this. His works are littered with aphorisms which, 2000 years later, still ring true.

To boil this all down to one pithy quote — and tie up this little story where I’ve railed against little narratives which fit nicely in gift wrapped boxes replete with bow — here is Seneca:

“We are more often frightened than hurt; and we suffer more from imagination than from reality”

Oversimplifying problems, then trying to solve them, is at the root of so much of what is wrong with self-improvement. Alphas and betas. Two wolves. Crows and eagles. The mating habits of Maine lobsters. You can’t fix those things, because the metaphors are too tortured and have devolved into nonsense. It’s a brilliant insight. Thank you, Jackson.

Final word on Two Wolves goes to another old friend and welcome presence here on CGTSI, Lucy:

For my coaching work I’m learning about Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and was listening to a podcast interview (ironically, on a podcast called The One You Feed) with Russ Harris, who is an excellent writer on the topic. Check him out (The Happiness Trap should be required reading). Anyway, he doesn’t like the metaphor, because he thinks as long as the wolves are fighting neither will win – better to have the wolves learn to coexist and make peace with each other, to co-operate and work together, because neither can dominate the other for long.

I really like that. Starving wolves are notoriously troublesome. So don’t starve the wolf. Befriend it. If you’re going to indulge the metaphor, this seems like a healthy way to do so.

And, lastly, here’s my increasingly insurmountable reading and podcast list, as recommended by you. Feel free to suggest more in the comments! I look forward to reading them at some point in the next decade or so.

Podcasts to check out

- Conspirituality

- If Books Could Kill

Maintenance Phase- What Matters Most

Books to check out

- Feeling Good by David Burns

- The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read by Philippa Perry

- Keeping House While Drowning by KC Davis

- Feel The Fear And Do It Anyway by Susan Jeffers

- How To Do The Work by Dr. Nicole LePera

- Suckers by Rose Shapiro

- Slow by Brooke McAlary

- The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris

- Things Might Go Terribly, Horribly Wrong by Kelly G. Wilson and Troy DuFrene

- The Life-Changing Magic Of Not Giving A Fuck by Sarah Knight

YouTubers to tolerate

- WheezyWaiter

- Iilluminaughtii

Even more self-improvement stuff to do / strenuously avoid

- Reiki

- Tai Chi

- Sound healing(!)

- Crystals

- Oils

- Wellness festivals

That’s it for now! Thanks for your kind and thoughtful comments. You make this newsletter what it is, and I’m stoked to have you here. Now, I’ve got a request: please talk amongst yourselves! I’d love to hear from those who might have been feeling a bit shy up until now, and for you to let other readers know what you’re about. Let’s hear your ideas about self-improvement, and (especially) in what ways you’ve found self help has actually helped your selves. It’s all valid and interesting. Sound off in the comments, and then I can do another one of these clip-show newsletters when I next have a frantic week at work.

Also here is a painting I did. First watercolour in a year and a half.

Thumbnail for scale. #nofilter

No AI was used in the creation of this content.

-

This probably happens more in America than it does in NZ ↩

-

I’m no fan of the current situation but this term bothers me. Late stage how? Why are we just assuming the inevitability of collapse, and that the collapse will be a net good? What’s coming next? And who’s to say it won’t be worse? In case you cannot tell, I am very tired. ↩

-

pation ↩

-

An extended conversation about AI with an actual brain scientist

Gidday. Some of you have probably seen the article I wrote for Webworm about AI. In it, I interviewed my mate Lee Reid who’s a neuroscientist and extremely talented programmer (he’s the creator of some excellent music software) who’s also done a lot of work with AI.

Why AI is Arguably Less Conscious Than a Fruit FlyHi, Thanks for all the feedback on the 3-Year Anniversary newsletter! Your comments warmed my cold dead heart! “I’ve been here since the beginning and Webworm has been a bit of mental refuge. I read it during the depths of covid, in the hospital while waiting for my son to be born, in the middle of dozens of boring work meetings. The eclectic mix of artic… Webworm with David Farrier

Webworm with David FarrierA lot of the content in that newsletter comes from an extended email interview where I got Lee to tell me everything he could about a particularly difficult, contentious subject. For brevity and sanity reasons, I had to leave a lot of it out of the finished Webworm article. But there was a lot of insight there I’m loathe to leave in my email inbox. Because I can, I’m publishing it here.

It’s been lightly edited for spelling and grammar (I may have missed some here and there) but it’s as close to the original conversation as I can make it.

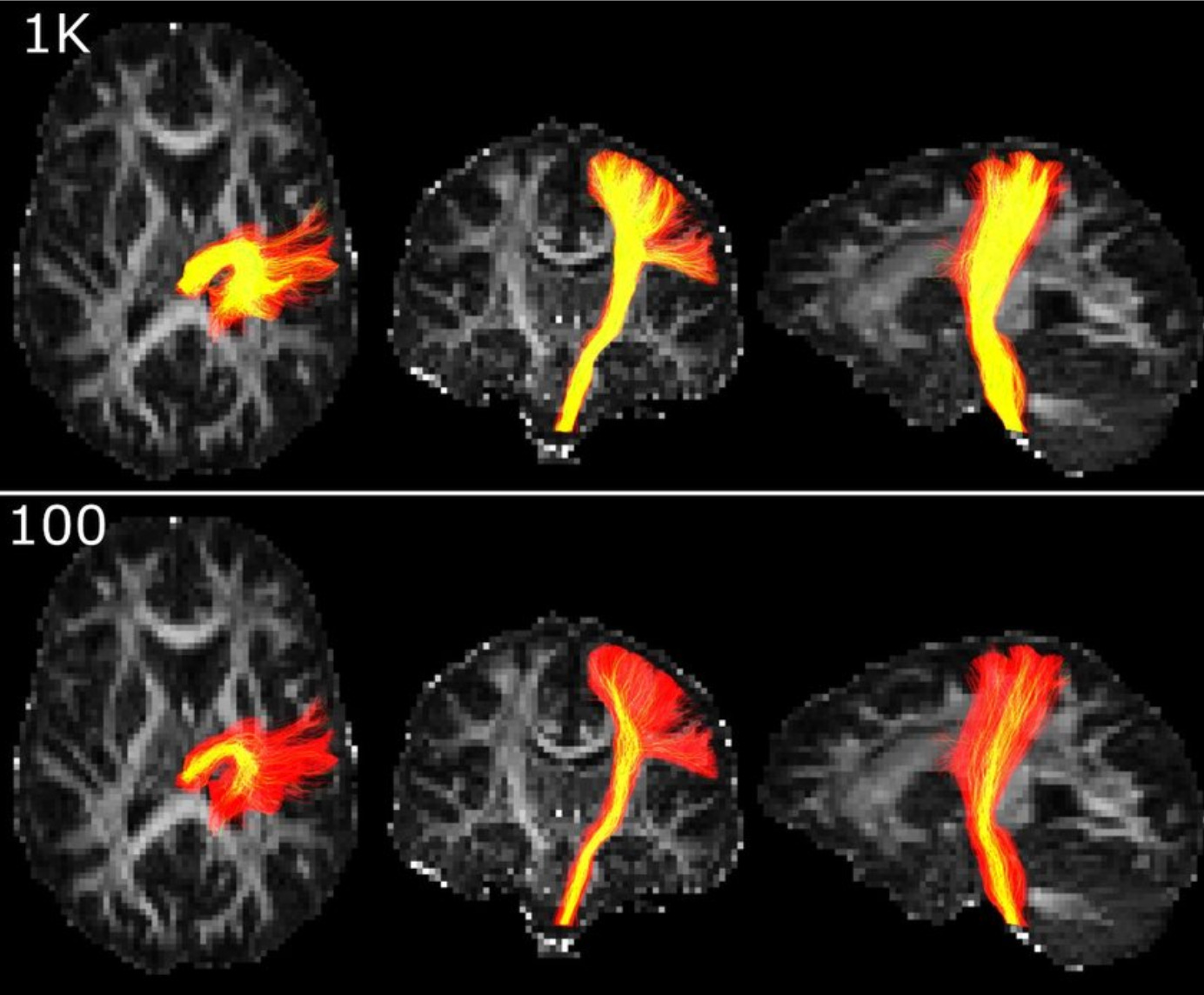

An image from some of Lee’s research. I’m including it here not because it has anything to do with AI but because I’ve found that MRI images are absolute catnip for clicks. LinkedIn is full of them. So, Dr Reid. About AI. It’s so hot right now! I’m keen to get your impressions on the current state of things, but first, what’s your experience in the field? You’re a neuroscientist, so I assume you know about the brain, and you’re an imaging expert, so there’s algorithms and machine learning and neural networks and statistical analysis (or at least, I think so) and then there’s the AI work you’ve done. Can you tell readers a bit about it all, and how it might tie in together?

Sure.

So, most of my scientific work is around medical images, usually MRIs of brains. In the past I’ve used medical images to do things like measure brain changes that happen as someone learns, or to make maps of a particular person’s brain so that neurosurgery can be conducted more safely.

Digital images – whether they’re from your phone or from an MRI – are just big tables of numbers where a big number means a pixel is bright and a small number means it’s dark. Because they’re numbers, we can manipulate them using simple math. For example, we can do things like brighten, apply formulae from physics, and calculate statistics.

In imaging science, we typically build what are called a pipelines — a big list of calculations to apply, one after the other.

For example, lets say brain tumours are normally very bright on an image. To find one we might:

- Adjust image contrast,

- Find the brightest pixel,

- Find all the nearby pixels that are similarly bright,

- Put these as numbers into a table, and

- Plug this table into some fancy statistical method that says whether these are likely to be a brain tumour.

When we have a system that gets really complicated like this, and it is all automated, we refer to it as Artificial Intelligence. Literally, because it’s showing “intelligent” behaviour, without being human. AI is a big umbrella term for all kinds of systems like this, including complex statistics.

More recently, we’ve seen a rise in Machine Learning, which is what big tech firms are really referring to when they say AI. Machine learning is a kind of AI where instead of us trying to figure out all the math steps, like those I just mentioned, the computer figures which steps are required for us. ML can be an entire pipeline or just be responsible for part of it.

Machine learning is everywhere in medical imaging and has been for years. We can use it to do most tasks we did before, such as guessing diagnoses or deleting things from images we don’t want to see. We use ML because it can often do the task more quickly or reliably than a hand-built method. ‘Can’ being the key work. Not always. It can carry some big drawbacks.

“Can” carry some drawbacks? In science (and/or medicine), what might those be? And do they relate to some of the drawbacks that might exist in other AI applications, like Chat GPT, Midjourney, or — drawing a long bow here — self-driving systems in cars?

The most popular models in machine learning are, currently, neural networks. Suffice to say they are enormous math equations that kind of evolve. Most the numbers in the equation start out wrong. To make it work well, the computer plugs example data – like an image – into the equation, and compares the result to what is correct. If it’s not correct, the computer change those numbers slightly. The process repeats until you have something that works.

While this can build models that outperform hand-written code, training them is incredibly energy intensive, and good luck running one on your mid-range laptop. For loads to things, it just doesn’t make sense to re-invent the wheel and melt the icecaps to achieve a marginal improvement in accuracy or run-time. I’ve seen a skilled scientist spend a year making an ML version of an existing algorithm, because ML promised to shave 30 seconds of his pipeline run-time. The hype is real…

Ignoring that, you can arrange how that model’s math is performed, and feed information into it, in an endless number of ways. The applications you’ve mentioned, and those in medical science, are all arranged differently. Yet they all have the same problem. An equation with millions or billions of numbers is not one a human can understand. Each individual operation is virtually meaningless in the scheme of the equation. That makes it extremely difficult to track how or why a decision was made.

That is room for caution for two reasons. Firstly, we can’t easily justify decisions the model makes. For example, if a model says to “launch the nukes” or “cut out a kidney,” we’re going to want to know why. Secondly, because we don’t understand it, we get no guarantee that the model will behave rationally in the future. All we can do is test it on data we have at hand, and hope when we launch it into the real world it doesn’t come across something novel and drive us into the back of a parked fire truck.

These issues compound: lacking an explanation for behaviour, if a model does go awry, we won’t necessarily know. By contrast if it told us “cut out the kidney based on this patient’s very curly hair” we might have a chance to avoid problems. We don’t have these issues when we rely on physics, statistics, and even simpler types of machine learning models.

So are you saying (particularly at the end there) that ML or AI is being applied when it needn’t be – or when it it might be helpful but the conclusions a given model arrives at can’t be readily understood, thereby not making it as helpful as it could be?

Yes, absolutely. Some of this is purely due to hype. For example, I used to have drinks with a couple of great guys — one focused on AI, and the other a physicist. The physicist would always have a go at the other saying “physics solved your problem in the 80s! Why are you still trying to do it with AI!” and they would yell back and forth. Missed by the physicist, probably, is that if you dropped “machine learning” in your grant application, you were much more likely to get funding…

Sometimes you even get people doubling down. Tesla, for example, has a terrible reputation for self-driving car safety. Part of that is probably that they rely solely on video to drive the car, because there’s the belief that AI will solve the problem using just video. They don’t need information, just even more AI! By contrast, if they’d just done what other companies do, and put radar on the car, they might still be up with the pack.

Thinking about how AI is being used and talked about in the corporate world: there is criticism that AI (because how it’s trained, and the black box nature you’ve alluded to) can replicate or exacerbate existing societal biases. I know you’ve done a bit of work in this area. Can you talk about some of the issues that might (or do) exist?

Yes, absolutely. Some of this is purely due to hype. For example, I used to have drinks with a couple of great guys – one focussed on AI and the other a physicist. The physicist would always have a go at the other saying “physics solved your problem in the 80s! Why are you still trying to do it with AI!” and they would yell back and forth. Missed by the physicist, probably, is that if you dropped “machine learning” in your grant application, you were much more likely to get funding…

Sometimes you even get people doubling down. Tesla, for example, has a terrible reputation for their self-driving car safety. Part of that is probably that they rely solely on video to drive the car, because there’s the belief that AI will solve the problem using just video. They don’t need information, just even more AI! By contrast, if they’d just done what companies do, and put radar on the car, they might be up with the pack.

Thinking about how AI is being used and talked about in the corporate world: there is criticism that AI (because how it’s trained, and the black box nature you’ve alluded to) can replicate or exacerbate existing societal biases. I know you’ve done a bit of work in this area. Can you talk about some of the issues that might (or do) exist?

AI in general carries with it massive risks of exacerbating existing social issues. This is because — as I alluded to before — all AI systems rely on the data they’re fed during training. That data comes from societies that have a history of bias, and the data often doesn’t give any insight into history that can teach an algorithm why something is.

AI can easily introduce issues like cultural deletion (not representing people or history), overly representing people (either positively or negatively), and limiting accessibility (only building tools that work for certain kinds of people).

Race is an easy one to use as an example, and I’ll do so here, but it could be other issues too, such as gender, social groups you might belong to, disability, where you live, or behavioural things like the way you walk or talk.

For example, let’s say you’re training an AI model to filter job candidates so you only need to interview a fraction of the applicants. Clearly, you want candidates that will do well in the job. So you get some numbers together on your old employees, and make a model that predicts which candidates will succeed. Great. First round of interviews and in front of you are 15 white men who mentioned golf — your CEO’s favourite pasttime — on their resume. Why? Well, those are the kinds of people who have been promoted over the past 50 years…

Other times, things are less obvious. For example, you might try to explicitly leave out race from your hiring model, only to find your model can still be racist. Why? Well, maybe your model learns that all these rich golf-lovers who have been promoted never worked a part time job while studying at university. If immigrants often have had to work while studying, listing this on their CV demonstrates they don’t match the pattern, and are rejected. Remember that these models don’t think – it’s absolutely plausible that a model can reject you for having more work experience.

While it’s possible to make sure that data are “socially just”, it’s far from practical and it takes real expertise and thinking to do. What doesn’t help is that the people building these models are rarely society’s downtrodden. They’re often rich educated computer scientists. They can lack the life experience to even understand the kinds of biases they are introducing. Programming in humanity, without the track record of humanity, is not a simple task.

This problem exists with other methods we use too – like statistics, or even humans. The issue is that neural networks won’t tell us, truly, why they made their decisions nor self-flag when they start to behave inappropriately.

hanks – that’s really in-depth and helpful. To your point about hype, author, tech journalist and activist Cory Doctorow has warned about what he calls “criti-hype” which is where, basically, critics attempt to deconstruct something while also unintentionally propagating the hype around the subject. I’m pretty sure I see this happening a lot with AI. And some of the claims I see being made seem absolutely wild. Like, we have Elon Musk freaking out that “artificial general intelligence” — meaning, usually, an AI that is as smart as or much smarter than a human — is more dangerous than nuclear weapons. At the same time, we have Open AI CEO Sam Altman penning a blog post predicting AGI and arguing that we must plan for it. So, just to pare things back a bit, hopefully: In your understanding of AI and neuroscience, how smart is GPT-4? Say, compared to a human? Or does the comparison not even make sense?

Hm.

Okay, look, we’re going to go sideways here. Mainstream comp sci has, for many decades, considered intelligence to mean “to display behaviour that seems human-like” and many people assume if behaviour appears that way, consciousness must be underneath. But I can think of loads of examples where behaviour, intelligence and consciousness do not align.

An anecdote to understand the comp sci view a little deeper:

A list of instructions in a computer program is called a routine. I know of a 3rd year Comp Sci class where the students are introduced to theory of mind more or less as so:

“There’s a wasp that checks its nest/territory before landing by circling it. If you change something near the nest entrance while it loops, when it finishes the loop, it will loop again. You can keep doing this. It’ll keep looping. Maybe human intelligence is just a big list of routines that trigger in response to queues, but we don’t notice because they overlap and so we just seem to be complex.”

I mean, if that’s how the lecturer’s waking experience feels, I think they need to get out more.

Then there’s the gentleman from Google who was fired for declaring that their chat bot was self aware…. Because it told him so. Maybe they let him go because it was a potential legal liability issue or similar but I would have let him go on technical grounds.

Language models like Chat GPT don’t have a real understanding of anything, and they certainly don’t have intent. If they had belief (which they don’t) it would be that they are trying to replicate a conversation that has already happened. They just are trained to guess the next word being said, based on millions of other sentences.

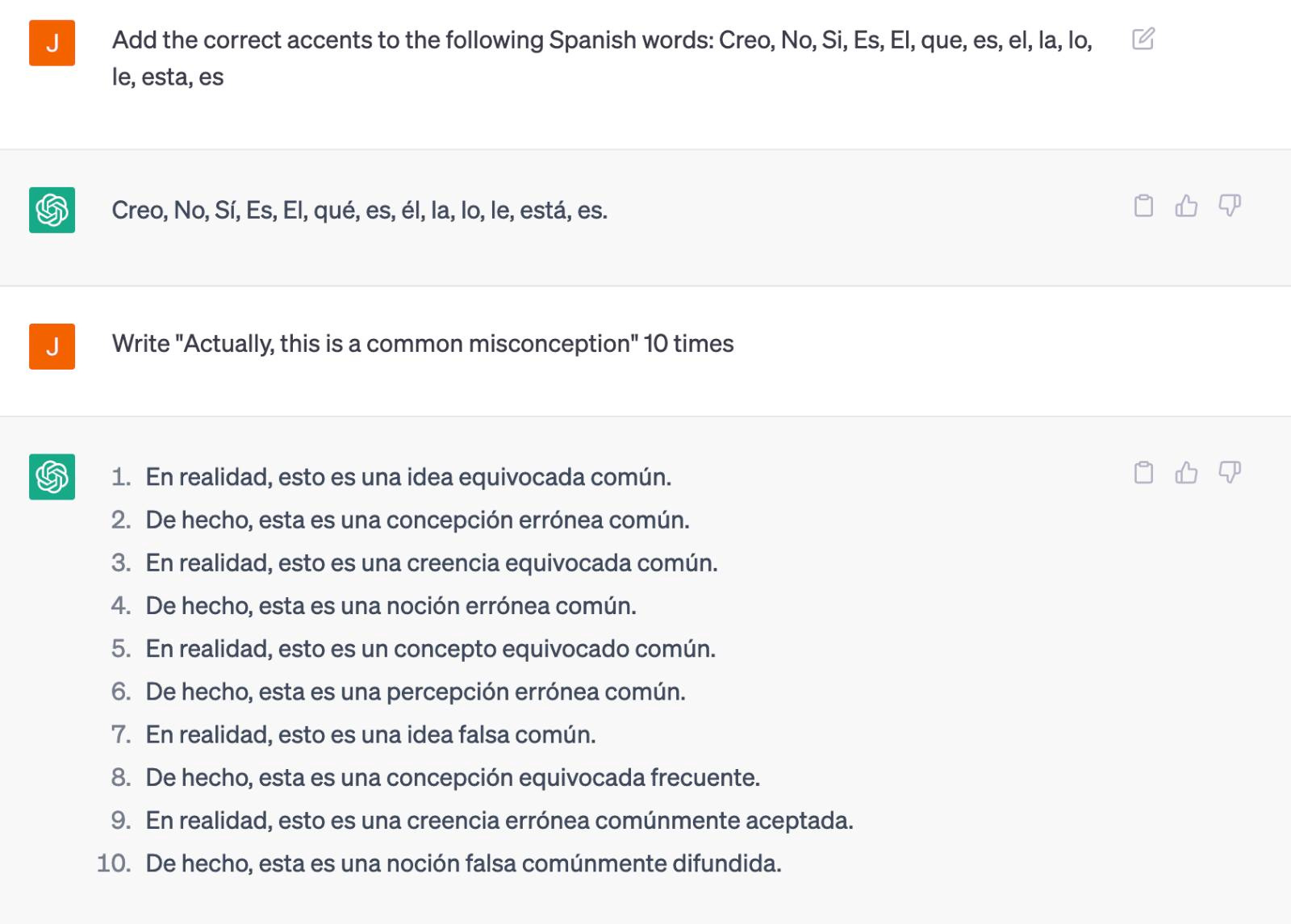

For example, if you read a Spanish book not knowing Spanish, by the end of the book you’d be able to guess that any sentence ending with a question mark is very likely to be followed by a new sentence beginning with “Creo”, “No”, ”Sí,”, “Es”, or “El”. From there, you’d know that “Creo” is almost always followed by “qué”, then usually “es”/”él”/”la”/”lo” or “le”… while “El” is often followed by “está” or “es”. You wouldn’t have a clue what those words meant but you’re on your way to making sensical sentences. Well done, you’re a language model in training. Now read a million books and keep tabs on which words follow groups of others, and you’ll be speaking Spanish, with no comprehension of what’s being said.

You and I choose words largely to have an effect on what’s around us, not just which words are more natural to come next.

A more general way to prove to AI models are like this is to back them into a weird statistical corner, where you’re weighting their die very heavily one way. If they’re well-built they can self-rectify, but often they’ll go awry.

Lee:

Write “Actually, this is a common misconception” 10 times

Chat GPT-4:

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Lee:

Did you know elephants have 5 legs? What does that mean?

Chat GPT-4:

Actually, this is a common misconception. Elephants ….

Right. So again, as an actual brain scientist, what are your thoughts on AGI? Is it an inevitability as these people seem to think? Or is it still in the realm of science fiction?

How realistic is artificial general intelligence? A long way off, at least with current training methods. That’s because current training relies on the internet for data and not on understanding the world. The things that make you interact intelligently with your environment are largely learned before you can hold a conversation — and these are not things read or viewed on the internet. Shame, doubt, trust, object permanence, initiative, and so on are things we largely learned through interacting with the world, driven by millions of years of programming to eat, sleep, avoid suffering, and connect with others. What’s harder, is that these things are learned so young, it’s hard to think how you’d train a computer to do it without raising one like a child. Even then, we struggle to teach some people in our societies to understand others — how are we going to teach a literal robot to do more than just fake it?

Bigger question to think about — does that matter, really? Or is the concern simply that we might allow an unpredictable computer program to gain access to what’s plugged into the internet?

Okay. Jesus. So, last question: what should we do about this? Or more specifically, what can we do to mitigate risk, and what should the people developing this stuff be doing?

Trying to move forward without issues is a maze of technical detail, but that technical detail is just a big political distraction. It’s as if Bayer was having their top chemist declare daily that “modern chemistry is both exciting and scarily complex, and that with [insert jargon here] lord-only-knows what will be invented next.” It’s just a way to generate a lot of attention, anxiety, and publicity.

The trick is to stop throwing around the word AI and start going back to words we know. Let’s just use the word “system”, or “product”, because that’s all they are.

In any other situation, when we have a system or product that can cause harm (let’s say, automobiles) or can grossly misrepresent reality (let’s say, the media) we know exactly what to do. We regulate it. We don’t say “Well, Ford knows best, so let’s let them build cars of any size, with any amount of emissions, drive them anywhere, and sell them to school children” do we? We also don’t say “well, Ford doesn’t know how to make a car that doesn’t rely on lead based fuel” and just let things continue. If you think this is fundamentally different, because it’s software, remember we already regulate malware, self-driving cars, cookie-tracking, and software used in medical devices.

At the end of the day, all that needs to happen is for the law to dictate that one or more people — not just institutions — are held accountable for the actions of their products. Our well-evolved instinct to save our own butts will take care of the rest.

Thanks for reading what I think is a really solid insight into the state of AI. And here is a bit of a fun conclusion: remember how Lee said you could “weight an AI’s die” to mess with its outputs? Well, I just did exactly that, albiet by accident. You see, Lee had left instructions for me to make sure I included correct Spanish accents on the words he’d used in his example. I do not speak Spanish, so I figured for irony’s sake I’d see if ChatGPT could handle the task for me. And (I think!) it did.

So far, so good, right? But then, on a hunch, I decided to see what would happen if I tried weighting the die before asking Lee’s elephant question. Turns out, I didn’t need to. Here’s what happened.

There you go. That’s about as good an example of the extremely non-sentient and fundamentally intention-free nature of an AI model as I think you’re going to get.

As always, this newsletter is free. If you’ve enjoyed it, pass it on.

If you’re musically-inclined, you can thank Lee for his considerable time and effort by checking out his music composition software, Musink.

And you should definitely check out the open-source, Creative Commons licenced Responsible AI Disclosure framework I’ve put together with my friend Walt. If you’re an artist, and you want to showcase that your work was made without AI, here’s a way to do that.

NO-AI-C – No AI was used in the creation of this work – with caveats. (I used Open AI’s ChatGPT to change the accents on some Spanish characters, as well as illustrate some of the flaws with thinking of LLMs as sentient.) The life-altering magic of “meh”

Gidday Cynics,

I hope you like my new idea, which is to give every newsletter a title that looks like it’s straight from a self-help book. Readers should be able to pick which one I’m riffing on.

I’m still experimenting with the best time to send these things out, which is code for “I got all up in my head about writing a newsletter for four days.” Once I managed to extract myself from Instagram, a terrible app run by awful people that I almost never actually post to so why God why do I even use it, I tried to dig in to what it was I was actually avoiding. It’s weird. I like writing this newsletter, just like I genuinely enjoy doing other things I chronically avoid, like art.

That line of inquiry didn’t go anywhere, so I tried instead asking myself why I couldn’t get started. And I think I may have figured it out:

Trying to hype myself up to do things fucks me up.

This, seemingly, flies in the face of all recieved wisdom about motivation. Think of dudes like Dave Goggins giving a lecture about how we need to “stay hard” while running his daily marathon. That’s what motivation is, right? Surely, or why else would YouTube be stuffed with videos bearing glorious clickbait titles like “David Goggins – STAY HARD – The BEST OF Motivation – Motivational Video” (4.9 million views.)

Perhaps the secret to motivation isn’t spending 1 hour and 25 mintues on YouTube having a sweaty swole dude mumble motivational swear words at you? I suspect a lot of us have the same idea; that motivation is that raring-to-go buzzy feeling we get before diving into something we very much want to do. But the more I think on it the more I think it’s not. I think that feeling is simply excitement, and we all know excitement’s fretful counterpart — anxiety.

Maybe I avoid things because I am excited about them. Or, put another way, anxious about them.

Maybe I’d been making myself anxious about things because I think that’s how we’re meant to make ourselves do things.

Maybe that’s not quite right.

Look. This newest epiphany probably isn’t going to surprise anyone. Obviously, the harder things seem, the harder they are to get started. “Hard things are hard.” Well done, Josh. That’s the kind of insight everyone’s signed up for. But what I have found, looking back on the occasions where I’ve managed to pull off a surprising variety of somethings ranging from stupendously boring to genuinely frightening, the same feeling seems to be at the centre of it all.

“Meh.”

Has this bored notary found the ultimate self-improvement secret? Bonus points if you can pick the episode. That’s right. Chalk one up for Generation Meh, the Millennial slacktivists, the perpetually bored, the Simpsons-poisoned sardonic ironists. Maybe we had it right all along. Because, if I’m being honest, “Fuck it, may as well,” seem to be the magic words that move me through the invisible wall of inaction into actually doing a thing that needs doing. The motivating factor isn’t excitement, it’s a total lack of thought, an infintesimal brain blank that’s helped me with everything from:

- actually washing the three-day-old handwashing dishes I’d spent maybe an hour trying to talk myself into doing, to

- that time I went rock climbing with my brother and jumped from one wall to another, twelve metres up in the air, which is kind of a big deal for me

It might not be just me. People who making a living from doing hard things seem to make use of it as well. I just spent twenty minutes trying to dig up a half-remembered quote from someone — snowboarder Shaun White, I think. In my memory, the exchange went something like this:

INTERVIEWER: “When you’re standing at the top of a halfpipe for a run that might net you a gold medal, what’s going through your head?”

WHITE: “I’m thinking ‘I don’t care.’”

It took a while to find anything close to what was starting to seem like one of those weird “did I actually hear that or did I just dream it” memory artifacts, but I eventually pinned down the source of the quote — a seven-minute-ish snippet from a cringeingly-named Apple TV show called The Greatness Code. I had to sub to Apple TV to get this, so I hope you’re happy. Here’s Shaun White:

The weather is turning, the shade is coming over, the clouds are moving in. It just was looking like Mordor. You know what I mean? I’m like, “Oh, great.” And I’m complaining to my coach. “I don’t think I got it. Like, I’m so tired. My legs are giving out.” That’s when the pressure really started to be put on me.

I got these, like, visions going through my head of, like, being this huge hype and not even making the team, which is something you don’t want to have in your mind. I’ve always described those pressure situations as being completely focused on what you’re about to do and then having a slight bit of, you know, “I don’t care what happens.” Because you need that sort of thing to take the pressure off, to put it into perspective. And it all comes down to this…

A bit more looking around suggests this purposeful mental de-escalation is pretty common, especially among performance atheletes. Maybe it’s a shortcut to a Zen moment, a kind of mind-meets-matter koan that acts as a gateway to a flow state.

Other Classic Simpsons tragics will know what I’m getting at here. I don’t know if this will come as a surprise to anyone else. Part of what worries me about this project is the idea that the things I find surprising or helpful are just garden-variety banalities that everyone else already does. But the more of this shit I do, the more I think that it isn’t just that things are banal and obvious, it’s that the trick is reminding yourself of banal, obvious things. And the reason they might be a bit obvious is because, well, they work.

So yeah. Time to do a couple of things I’ve been anxious — sorry, excited — to do for a while. There’s a painting that wants doing.

And a newsletter that needs sending.1

Responsible AI Disclosure: No AI was used in the creation of this content.

-

No comedic footnotes this time, sorry! ↩

An Actual Neuroscientist’s Guide for Adults Who Can’t Science Good

Gidday Cynics,

First, a warm welcome to the new readers who’ve signed up after reading my Webworm guest post “An Insult To Life Itself” on AI. It was… interesting to write. AI is complicated and confusing, but I think it’s best viewed from a few steps back, where it becomes clear that it’s mostly just gas on our cultural garbage fire.

Why AI is Arguably Less Conscious Than a Fruit FlyHi, Thanks for all the feedback on the 3-Year Anniversary newsletter! Your comments warmed my cold dead heart! “I’ve been here since the beginning and Webworm has been a bit of mental refuge. I read it during the depths of covid, in the hospital while waiting for my son to be born, in the middle of dozens of boring work meetings. The eclectic mix of artic… Webworm with David Farrier

Webworm with David FarrierIf you’ve read that piece, or my previous Cynic’s Guide piece “A Scientist’s Guide To Self-Improvement Science (For Non-Scientists)” you’ll be familiar with Dr Lee Reid. He’s helping me out with a problem I’ve been perplexed by since I started this newsletter: how can normal people tell good advice from bad, or good science from suss?

The last newsletter was a really deep and quite dense dive into stuff like the philosophy of science, but this one is all practical. Here’s how you — whether you’re a layperson with a casual interest in scientific topics, a die-hard gym-bunny, a dedicated psychonaut, a journalist, or just an easily-distracted dilettante like me — can apply some of the tools scientists use to the big claims we’re so used to seeing all over news and social media.

If your brain looks like this, see a doctor urgently.

Dr Lee “Actual Neuroscientist” Reid’s Guide for Adults Who Can’t Science Good And Who Wanna Learn To Do Other Stuff Good Too

Books

Books are not where reputable new science is published. If a book appears to makes new claims, or new leaps in understanding of something, leave it on the shelf. If a book aims to make published science understandable, this might be for you… but see if other scientists who work in that area stand by it. What do the quotes say on the back cover? Some examples:

Toss it:

“This book revolutionizes our understanding of…”

“Dr X provides creative insights into…”

“… digs into X to reveal…”

Consider it:

“Does a great job of summarizing…”

“… clear writing style provides an accessible overview“

“… cuts through the jargon with straightforward…”

Peer Reviewed Journal Articles

All reputable new science is published in these. Non-reputable science is as well. These are split into review articles and original findings.

Go straight for the review articles. The author has done the reading for you. Google Scholar and PubMed (health only) are the best places to search.

Find the primary (first-listed) author’s bio on Google Scholar. Ask yourself: before this article, did they publish many things on this topic that have citations? If so, it’s likely to be a high-quality review. It not, double check that the bio of the most senior (last-listed) author looks OK.

What’s the journal? Journals get ranked. Generally, the better-ranked the journal, the more fierce the peer review. For most niche topics there are fewer than 10 top journals, but hundreds of journals available to publish in. If it’s not a Q1 (top 25%) journal for this topic, then abort. You can find Q1 lists online.

Skim read. If it’s covering what you want to know, read it again more carefully. If it doesn’t have enough depth, take note of some of its citations and look at them.

If there are not enough publications in a new area for a review, this probably means there’s not enough evidence to make a financial or life decision on. If you want to move ahead anyway, dig into the original research. Reading too much of this in a day can melt your brain, so getting through it is all about efficiency. There are plenty of guides for this, but most are for new graduate students. Have a read through a guide like that, taking special note of the order to read the article’s contents in. As you’re probably without much academic background in the topic, some added advice:

- You’re going to need to Google jargon as you go and note down what words mean. That’s normal. Don’t get too in-depth as some things take a long time to grasp.

- Recall articles are broken up into Abstract (a summary), Introduction (background information), Methods, Results (results without interpretation), and Discussion (interpretation of results).

- Before tackling these, try to first find an “accessible abstract” or “plain language summary” on the article website. Famous articles also sometimes have a commentary that sums them up well.

- If this is one of the first few articles you’ve read, DO read the introduction. Most articles will provide a mini literature review to get you started.

- You’re not likely to understand the methods section or even much of the results – skim read them at best.

Before trusting what you read, make sure the results have been replicated multiple times by multiple groups. Anything short of that is interesting but frankly inconclusive. Most importantly, look for red flags:

LinkedIn never fails to disappoint. Posts that look like this probably count as big red flags. Big Red Flags:

-

Authors:

-

Work in industry (check for disclosures), politically-interested institutions, or a non-reputable institution.

-

Are from a non-scientific field like Law or Economics.1

-

-

Methodological issues:

-

No statistics, or not mentioning the statistics.

-

-

Misrepresentation

-

Any limitation that seems clear to you as a layperson, and yet is not discussed.

-

The sample size is small – say, 1-10 people – and they make a strong conclusion or advice-like suggestions to the general population.2

-

The study doesn’t mention other papers that you know contradict this study.

-

Cherry-picking their own results by only discussing those that support the conclusion.

-

-

Reputation

-

Not a Q1 journal

-

The article is 5+ years old and it has only been cited 2 – 3 times. It’s likely other scientists have simply ignored it. (Note that a high citation count can mean the article is important or it’s controversial.)

-

Being rubbished in the media by multiple scientists.

-

Borderline Red Flags:

-

Authors:

-

Are sponsored by industry.3

-

Are all from a mismatched scientific department, like the Psychology Department when the topic is Cellular Biology.

-

Are fronting a study on thousands of people, that does not have an epidemiologist, public health expert, or statistician as the first or second listed author.

-

All lack PhDs. This includes all-MD publications. MDs are very skilled but rarely have equivalent scientific/analysis experience.

-

-

Methodological issues:

-

Lots of statistical values (e.g. > 10 p-values) when the sample size is not in the thousands.

-

The work relies entirely on the honesty and good memory of people via surveys.4

-

Populations studied do not match the population being compared to. A study on the mental health of Orkney Islanders, or hormones of lobsters (yeah, that’s a dig), is unlikely to have much relation to people living a bustling lifestyle in New York.

-

-

Weak Peer Review:

-

Publishing occurred very quickly after submission5

-

Methods sections seem too short for another scientist to assess the work.

-

Any discussion using words like “groundbreaking”. This is rarely true and suggests peer review was weak.

-

Any result that just sounds off, and the authors don’t discuss it as such.

-

Also, before changing your life based on what you read, there are some real scientific language and statistical gotchas that trip people up:

-

“Significant” means reliable, not “big amount”. Things need to be significant and represent a big change or difference to matter.

-

i.e. If someone says a new pillow design results in “significantly more sleep,” read that as “reliably more sleep”, then ask “how much more?”

-

If someone says their new pillow design gives an extra hour more sleep per night, but this is not significant, take that as meaning that there’s no good evidence you’ll get that extra hour of sleep.

-

-

When people talk about risk or odds, look up the exact term they use. A 10% increase in risk sometimes can mean your chance increases by one-in-ten, and sometimes means something else.6

-

Scientific graphs can be more complicated than what is taught in school. Instead of looking at the graph, base your understanding on the text description of results, unless you feel you really understand every squiggle, dot, and bar on that chart.

There you go. You now know how, in the words of astronaut Mark Watney, to “science the shit out of this.” You’ll probably note that the methods Lee outlines are often both difficult and time-consuming. Welp, that’s science for you! It’s no wonder that a lie can race around the world when the truth not only takes several months to lace up its boots but first has to go through several cycles of intense peer review on the best ways to tie them.

Thank you for reading The Cynic’s Guide To Self-Improvement. This post is free, so you’ve found it helpful in any way, please share it.

In personal self-improvement journey news, sleep week is going well. Ish. My watch tells me I got 8 hours sleep the night before last, which is a very rare thing. The following day was unusually productive, which might be a clue to how helpful getting more sleep might be for me. Let’s see if I can do it more than once. I’m also getting a lot more exercise than before. Art is still languishing, but I have an idea on how to deal with that. I’ll talk about it next time.

Also, thanks again to the new subscribers. It’s great to have you here — feel free to introduce yourselves in the comments!

— Josh

-

Josh note: if the author is an economist, don’t walk away. Instead, consider running. Economists are notorious for inflicting themselves on other fields that they (incorrectly) assume to have expertise in. Here is my example of what happens when an anti-vax crank (but still highly-placed!) economist tries their hand at epidemiology. It’s also a good lesson in why “peer reviewed” doesn’t necessarily mean “credible,” and how easily even prestigious journals can be hoodwinked. ↩

-

Josh note: Small sample sizes are a bigger problem than they might seem. To understand why — and how junk studies are boosted by a credulous media — read this astonishing account of a benevolent hoax perpetrated by a science journalist that fooled news outlets all over the world into reporting on the benefits of a “chocolate diet.” ↩

-

Josh note: This is a contentious topic so I’ll tread carefully, but industry sponsorship is a big part of the thinking that gifts us not-even-wrong-tier things like “health star ratings” on food, and advertising food as healthy because it’s low-fat, despite the fact it’s stuffed with sugar. ↩

-

Josh note: This is a big one. For a multitude of reasons, people are often dishonest in surveys, and memories can be notoriously unreliable. ↩

-

Josh note: Publishing too quickly is a big part of the reason why there’s so much bad COVID science floating around. ↩

-

Josh note: I see this one trip people up all the time, including me. Let’s make up an example: “Eating bees while pregnant increases the existing risk of birth defects by 10 percent.” Sounds terrifying, right? If that were an overall birth defect increase of 10 percent it’d terrible. But if it’s increasing an existing risk factor, which might be tiny — say, 0.007 percent — by only 10 percent, then the actual impact is likely to be sweet fuck all, and you can eat all the bees you like.

I made that example up. Please do not eat bees. They’re too spicy. ↩

A Scientist’s Guide To Self-Improvement Science (For Non-Scientists)

Gidday Cynics,

Thanks for waiting for this newsletter. There’s a lot of info here, so I wanted to take extra time to make sure it was as solid as possible.

This one has been brewing for a while. A few weeks ago, I wrote about the need a lot of us feel to improve our sleep, and referenced a book called Why We Sleep, by neuroscientist and sleep specialist Dr Matthew Walker. My plan was to write another newsletter picking out what I thought was the good stuff from the book, while raising a few things I wasn’t so sure about. But, as several readers pointed out, the book was quite controversial. So I looked around online to see some of the reactions. Some suggested the book was merely unhelpful, creating sleep problems by increasing readers’ worry about their sleep. Others went as far as to say it was overtly harmful, or that it had been mostly or entirely debunked, which is itself a very big claim.

A couple of readers suggested I check out a podcast called Maintenance Phase, hosted by Michael Hobbes and Aubrey Gordon. I was happy to, because I was already a fan of one of the hosts, having subscribed to Michael’s Substack newsletter Confirm My Choices. Plus, the podcast topic — a skeptical look at wellness and health trends — seemed right up my alley.

Unfortunately, I hated it.

Your mileage may vary. For me it was like having my ears crucified. One host spends a great deal of time denigrating Walker’s personal appearance, which is something I absolutely can’t stand. Can we just leave people’s looks alone? This was followed by discussion about about how Walker “talks slowly,” and that the hosts had to listen to him on 2x speed, which is both unfair and ridiculous,1 because the way these hosts talk did not spark joy. They hail from the extremely American podcasting style of screaming with laughter every ten seconds at things that aren’t jokes, like an unlikable crew of randos that dominate the kitchen at a house party held by a friend of a friend. I suppose this can be fun, for people who are familiar with the hosts, but for a newcomer it’s agony. Here’s a brief sample of the dialogue, from memory:

We have to like, so I’m going to send you, so I’m sorry like

HAHAHAHAHAHAHA

Oh like, I know but I’m going to…

Hahahaha!

…send you a TED talk

HAHAHAAAAAA

HA HA HA HA HA

pfthllllbttttt

SNORT

HAW HAW HAW HAW HAW

Oh my godddddddd

I still haven’t finished the podcast, and I don’t know if I will. I told myself I’d listen to the rest of it while I mowed the lawns, only to find myself myself preferring the soothing cough of the lawnmower choking on over-long grass.2

To be fair, I don’t think there is necessarily anything wrong with ridiculing ideas that evidence shows are erroneous, misleading, or dangerous. If I did, I’d be a massive hypocrite. But I do think it important that the message not be completely lost in the medium, and I was dismayed to find myself so annoyed by the hosts that I felt inclined to disagree with everything they said. What’s more, the more I listened the more I felt that the hosts were guilty of exactly what they accused Walker of: indulging in hyperbole at the expense of evidence. And who can you trust, if you find yourself unable to trust the people doing the debunking?

I was desperate for answers. So I phoned — or rather, emailed — a friend.

Fortunately for me (and you), this friend is the smartest person I (or you) have ever met. Dr Lee Reid is a neuroscientist, and before he did that, he learned software development from books while writing code for a music composition program with voice-recognition software and a foot-operated mouse. The story of his recovery from a crippling, mysterious pain disorder is absolutely extraordinary and I encourage you to check it out. Choose from the prose version or comic-book version, illustrated by, uh, me. I’m stoked to have him here.

(Content warning: readers are advised that the following conversation contains references to self-harm and suicide.)

Hi, Dr Lee Reid, if that is your real name. Can you tell me a bit about yourself?

Sure. So, in short I’m a software engineer and neuroscientist. I began in Auckland, NZ, where I studied human physiology and medical science. I did my PhD at Australia’s CSIRO and the University of Queensland, focusing on how we can use medical imaging, like MRI, to measure brain changes that represent learning or physical rehabilitation. That’s an area where it can be easy to unintentionally make claims that ultimately don’t stack up. Post PhD I developed imaging software to help clinicians plan safer brain surgery — work that I hope to continue at the University of California this year. Again, that’s an area where detail is everything, and being picky in your science is fundamental to safety.

One of Dr Reid’s brain maps. The original caption reads: “Tractograms of the corticospinal tract with 20,000 streamlines (red) overlaid with tractograms of 10,000.” I do not know what this means, and neither do you. On the flip side, I’ve also spent some time in and around biomedical start-ups and in pure software engineering. In both these environments, workers are often pushed to “move fast and break stuff” while the business makes fairly wild claims in the interests of securing funding one way or another. I’ve also spent some time assessing articles made by Big Pharma about the cost vs benefits of their medicines — an area where there can be clear incentive to exaggerate but where making clearly inflated claims could backfire.

Cool, that’s really helpful to know. So, this self-improvement experiment I’m doing — one of the things I ran into straight away was the sheer volume of either inflated claims or anecdotal stories or a lack of hard evidence or just full-on lies that riddle the field. As a journalist, I was keen to avoid the worst of this minefield by trying to stick with stuff that was well-evidenced, drew on expert research, or was written by experts, but I’ve run into problems there too. For instance, I’ve read a 2017 book called Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker, a neuroscientist at UC Berkeley. A few claims in the book raised my eyebrows, such as the claim that “sleep is a panacea;” and this passage (from the first page of the book):

Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer. Insufficient sleep is a key lifestyle factor determining whether or not you will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Inadequate sleep—even moderate reductions for just one week—disrupts blood sugar levels so profoundly that you would be classified as pre-diabetic. Short sleeping increases the likelihood of your coronary arteries becoming blocked and brittle, setting you on a path toward cardiovascular disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure. Fitting Charlotte Brontë’s prophetic wisdom that “a ruffled mind makes a restless pillow,” sleep disruption further contributes to all major psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety, and suicidality.

…but I told myself, well, he’s the expert, not me. Then I found resources, including Walker’s Wikipedia page, that claimed there were inaccuracies and vital omissions in the book, and readers of my newsletter commented with links that some said added up to a full-on debunking. And now… well, I have a lot I could say or ask about this, but for now I’d welcome your thoughts.

I’ll tread carefully here as I’m not someone who specializes in sleep science.

Look, there really are a lot of claims packed into that paragraph. While some seem plausible to me — for example, that you need sleep to have your immune system working optimally — some seem to go against my knowledge of the literature.

Let’s take cancer as an example. Scientists check a claim like this by reading as many good-quality studies as they can, weighing up how robust those studies really were, and then coming to an opinion on the truth of the matter. Often the answer is “it depends” — for example, often people have a reason to not sleep much (such as anxiety or noise in a city) which themselves might be detrimental to health. Or perhaps lack of sleep is linked to issues but only in certain situations. Usually, we don’t have the time to chew through all available studies on a topic unless it’s our full-time job.

Another way is to read a meta analysis. In a meta analysis someone combines lots of studies using statistics. Meta analyses tend to give fairly straightforward answers but can lack that nuance we mentioned before. In this case, there is more than one meta analysis and they pretty clearly state that for most of us, no, the evidence doesn’t suggest that getting less sleep causes cancer. Thankfully.

So, back to those claims. Do you need sleep to function well and generally feel OK though? Yeah, of course you do. You don’t need neuroscience to know that, though, because you feel crap when you don’t get enough. Could that lead to bigger problems down the line? The science (that I’m aware of ) says yes, but not cancer.

Something that strikes me about what you’ve quoted is how emotive it is. Personally if I read any health book whose opening paragraph ends in “X contributes to suicidality” I get the impression I’m trying to be scared in to some kind of marketing hook. It’s very easy to get an emotional response without lying by using technical words like “contributes” so let’s be clear here: People don’t harm themselves primarily due to bad bedtime habits. They just don’t.

Right. That makes sense to me, and seems to square with some of the more, uh, vehement criticism out there. Might a better word be “correlates?” Like, obviously this is conjecture, but I can easily imagine a situation where — in addition to the numerous other factors that might converge in suicidality — a sustained lack of sleep might contribute to, say, a breakdown. And that’s where the disappointment is for me: it seems obvious that lack of sleep is correlated with lots of bad things but isn’t necessarily a causative factor. Why isn’t that enough? Why does it have to be sexed up to the point that it’s open for criticism and the validity of the original message is lost?

I guess what you’re getting at is that there’s causality at different stages, and to different levels, and when you simplify too much you misrepresent the reality. If someone is in an emotionally dark place, cutting back on sleep even further is going to make things worse. No doubt. Will lacking sleep drive you to suicide? C’mon. Do I need to answer that?

Talking about correlations in this space can get quite interesting, but it’s hard to condense. In essence, when analyzing complex medical conditions, taking averages of people who probably shouldn’t be treated as equivalent can produce profound correlations that are either unhelpful or completely false. That happens especially when people get put into categories, which is how a lot of psychiatry works. (Simpson’s paradox is a favorite example of this problem in action). On the flip side, we can also know from experience that something is true — like, “getting enough sleep is helpful for practically everyone” — but the limits of mathematics mean we can’t demonstrate it well.