Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Newsletter

I don’t like the drugs, but

In your most distant memories, you remember colouring in.

You remember being good at it, and being praised for being good.

But when you slip and colour outside the lines, you howl and hide like a beaten dog, and no-one can tell you why.

You learn to read, although “learn” is probably putting it too strongly. Reading happens to you the same way as breathing.

Reading is the best thing that is or ever will be. You can no longer hear the clamour of the confusing world, or feel the tension that seems to surge from your bones, that makes you sit bolt upright, vibrating, sensitive to the slightest touch or sound.

Reading makes it quiet. In books, things make sense. The world goes away.

The tics start when you’re about eight. They are annoyingly literal, like the ticking of a clock; a sound you make in your throat over and over and can’t stop.

They change form. Soon you are 11, and everything you say must be said again, like an echo. You do this sotto voce, lest people think you’re weird.

The other kids do hear it sometimes. They thought you were weird already, and this doesn’t help.

When you’re older, you’ll look this up on a whim, and find out it is called palilalia.

At the time, you thought it was merely demons.

You start finding it very hard to do things.

You are bright, everyone you talk to says so, and you’ve been moved up a year and are taking extra subjects in school.

But on certain tasks – mainly maths, but others too – genuine attempts to work fly dead into a towering, blank wall of mental impossibility.

Because you are so bright (everyone says so) it is assumed that this is a phase.

If so, it is a long one.

It continues until your late thirties, and then? It carries on, only worse.

Your childhood saviour, reading, has become a monster. Unfortunately, society has thought to gift you an infinitely long and perpetually interesting book. You wake up each day full of ideas, and a portion of the ability required to achieve at least some of your ambitions, only to have all this potential energy subsumed by reading bullshit on the internet. Every day. Every day!

It feels like one of those ironic curses, the kind bestowed by a malevolent genie, where the wish is thwarted even as it’s granted.

Each missed opportunity, every failure, every slight imperfection compounds, compresses the shame you feel down into a savage knot of guilt that builds, layer on layer, like a pearl made of pure shit. It sits in your gut, causes nausea, sends you running blindly from even the implication of obligation.

It’s not just hard to do the things you need to do; it’s all but impossible to do the things you want to do.

Can you talk about this, lighten the burden? You can not. If anyone knew how useless you really were, how flighty, how distracted, how lazy, you’d never work again.

Complicating this obvious fact is the competing reality that you have had a number of jobs that people seemed to think you were good enough at to give you money.

This dissonance does not help. Every day, you endure the static screech of an endless primal scream, black noise, the cosmic background radiation of your brain.

You can’t let it out. People would look at you funny.

You do overhear things sometimes. “Couldn’t organise a piss-up in a brewery.” Someone lets something slip. “Can’t do the simplest thing.” A backhanded compliment is reduced to a mere backhander. “You might be always late, but at least you’re always there.” These accumulate and fossilise in the tar-pit of your mind. They are who you are; an agglomeration of failures and frustrations so intense they surface when you’re trying to vacuum the floor and this fucking piece of lint just won’t fucking move.

The vacuum cleaner is noisy and makes it possible to yell without being overheard, so you do.

Of course you have ADHD. That’s not special. According to the latest of many ADHD books you’ve read, anywhere from 5 to 25 percent of people may have ADHD. That’s not a disorder, that’s an overly-generous pie slice. For context, that would mean here are three times as many people with ADHD as there are Libras – and there are around 680 million Libras.

Horrible.

For many, finding out they have ADHD is hugely helpful. For you, it doesn’t feel that way.

You get your diagnosis over Skype from an archetypical psychiatrist; an ineffable reduced-affect Martian giving the overwhelming impression that any given patient is just one of many items on a rapidly-growing list. He sighs his way through the checklist you filled in – ADHD is diagnosed from a checklist, and this is one of many reasons it is so easy to diagnose oneself with, as it is about as accessible and mentally taxing as a Facebook quiz – and gives you a $1000 verdict; combined-type ADHD, with elements of autism spectrum disorder.

You think: this does explain a lot.

The vicious anxiety. The constant distractability, unless you’re reading. Also the fact you could read from age 3 – quite weird, in hindsight, although of course to you it was normal. The crippling perfectionism. The tics. The absurd procrastination. The way you learned, in school, how to perform social norms like you were learning from a script; and it explains too your puzzlement at how students reacted to your mistakes and line-flubs when you said the wrong thing at the wrong time (which was always very confusing, because often the thing you were laughed at for doing was something that someone else had been rewarded for just a week or so ago). The way people looked at you expectantly, like a malfunctioning robot; wondering what new runtime error you were about to throw.

Now, as an adult, with a series of masks so embedded you can’t tell where they stop and flesh begins, you learn that some of this agony might have been optional.

You think: hooray, I guess?

Social media, which of course was the source of the first inkling you might have ADHD, is unhelpful. Once the algorithms learn that you are ADHD-curious, your feeds become wall-to-wall relatability. If 25 percent of the world’s population has ADHD, about half of them seem to have taken up as ADHD influencers. There is an enormous industry dedicated to selling coaching and courses and one-weird-tricks and likes and subscribes, all through the lens of, at long last, being seen.

At first being seen feels great. But soon enough, it starts to feel more like being watched. According to influencers, ADHD is the ur-condition, the cause and effect of everything in your life. Overly talkative sometimes? ADHD. Feel strongly about genocide? ADHD. Forgotten to do the dishes? ADHD. The influencers, hungry for the next viral hit, have strip-mined the human condition down to bedrock. The relatable becomes hateful, because there are no solutions in sight: just an endless parade of half-working temporary life-hacks that link to purchasable courses.

Everything is ADHD.

And when everything is, nothing is. Maybe ADHD, despite mountains of evidence, doesn’t exist at all. Or maybe you just don’t have it. There’s nothing different that explains you, apart from being a screw-up.

And even if you do have ADHD, this condition is permanent. You’re stuck with it. If you want a picture of the future, imagine shooting yourself in the foot — forever. The solution is, or appears to be, accepting there is no solution.

Except for one thing.

You don’t like the idea of taking amphetamines every day of the rest of your life, but it’s got to be better than this.

The generic ADHD medication Rubifen, Medsafe says,

is a central nervous system stimulant. It is thought to work by regulating specific chemicals in the brain that affect behaviour. It helps to focus attention, shut out distraction and allows impulsive people to think before they act.

The first few days on medication are astonishing. Everything snaps into focus. The cloud of amorphous haze in your head coheres into a single bright beam. Tasks that once had impossible weight become somehow airy. Things that have lain undone for days, months, years, slowly accumulating the slow gravity of guilt, get done. You message a friend:

“Is this what being normal is like?”

In a follow-up telehealth appointment, you tell your Martian shrink that it’s going great and you feel like you’re cured, and his face flickers momentarily like the ghost of emotion past has walked over his grave. Or it’s a video-call glitch.

After a time, you notice some things. Your jaw has a tendency to clench. Headaches set up evening and occasional matinee showings. Your mouth is dry. You find it hard to write, literally; your fingers freeze up on the keyboard and it is difficult to move them to the correct places. Sleep is erratic. You lose weight, without trying or particularly wanting to. Sometimes the anxiety is quelled; sometimes it seems to surge more than ever, like hot wires laid under the skin.

You notice, to your horror, that some of the tics seem to be trying to come back.

Slowly old habits manifest, like water released from a dam, determined to return to its old path. If you manage to wrestle the laser light of attention on to the right task, you might be all right. But if you should allow it to illuminate the endless well of shiny internet objects, God help you.

Eventually you are back where you started, but this time with side effects.

You don’t like the drugs, but it would seem the drugs can’t even give you the common courtesy of liking you back.

So you quit.

Some time later, in despair, hoping to plaster over the cracks in your facade that threaten to become structural, you start again.

The process repeats, and you quit once more.

Later again, when the weight of the big and small things you swore – and needless to say, failed – to do consistently seems ready to crush you, you start over.

You look at the capital letters on the box of Rubifen, the ones that say DO NOT STOP TAKING THIS MEDICATION.

This time, you decide, you’ll make quitting part of the plan. One or two days on, some days off. Apparently some people with ADHD find this works for them.

You hope it works for you.

You are here ⬇️

‼️A postscript I should definitely have put in before hitting send.

Hopefully you already know this, but if not: only take medication as prescribed by your doctor or psychiatrist. Abruptly quitting long-term prescribed medications, especially those that work on your brain, can have serious and dangerous side effects. If you are considering a change of medication for any reason, talk to your doctor first (which is what whoever the guy is in the story above really did do, honestly.)

Map of the Problematic

Map of the Problematic – The Cynic’s Guide to Self-Improvement Podcast0:00/1246.02068

Map of the Problematic – The Cynic’s Guide to Self-Improvement Podcast0:00/1246.02068A while back I set up a podcast to listen to while I mowed the lawns. It was ostensibly about weightlifting, by an outfit called Starting Strength, hosted by a bloke called Mark Rippetoe. I’d seen stuff by Starting Strength before – I’d used their YouTube videos to learn how to deadlift and squat when my bad form threatened to mutilate my spine – and when it came to novice lifting programmes they seemed to know what they were talking about. [1] I was looking forward to learning more about strength, and lifting, and sports science in general. I put on my headphones and got to work. [2]

I was rounding a tricky bit out on the front verge by the fence, one of those bits where the grass grows out long from somewhere the mower can’t quite get to. My frustration at this was compounded by a growing sense of confusion as the Texan drawls on the weight-lifting podcast turned their talk, for some reason, to solar power.

I wish I had examples of what I heard. Infuriatingly, I can’t find the recording anywhere in my various internet or app histories, which is sad, because it was very funny. The gist was that solar power doesn’t work. This perplexed me, because I have solar panels on my roof, and a battery next to my house. I can watch them work in real-time by turning the lights on. Of course, to give credit to Rippetoe and friends where probably none is due, he was talking about how solar power at scale doesn’t work. Which is also wrong, but for different reasons. This talk inevitably segued into general riffing on climate change, and how it was a myth (feat. manly guffaws). All this was, for reasons that remain mysterious, presented as a metaphor for weightlifting.

I don’t know a lot about lifting. Nor do I know much about climate change, in the scheme of things; I’m not a climate scientist. But I know a hell of a lot more about climate change than those yahoos. It was howler after canard, bullshit piled on bullshit so deep that it stopped being offensive and became riotous. I had to stop the podcast because muttering “that’s not right,” “well that’s wrong,” and “what the fuck?” under my breath — punctuated with occasional disbelieving yelps of laughter — was starting to attract looks from passers-by.

Mower parked for the moment, I did a bit more digging into Starting Strength’s online oeuvre. Their “how to lift” videos seemed excellent, and in aggregate, were about twenty minutes long. Time well spent. Their novice lifting programs seemed, to my untrained eye, fine. There’s plenty of stuff like interviews with strength coaches and athletes and the like, which I assume is also fine. The rest was dismaying. It was much less about strength and more a telling meander through the myriad pathologies of the modern American male mind. It’s a grab bag of conspiracist nonsense: there’s both climate denial (a recent episode features professional fossil fuel shill Alex Epstein opining about “the need for increased usage and accessibility of fossil fuels”) and Covid-denial (Naomi Wolf and other cultural dingleberries receive guest spots).

So yeah. They’re lunatics.

The implications are troubling. If I can’t trust Starting Strength’s ability to filter fact from fiction in their podcast, what am I meant to make of their fitness program? I don’t expect perfection, or anything close to it, from my sources of information. Nor do I require uniformity of opinion or values. But this stuff was so egregiously wrong it was difficult to look past it. I suppose the real question is: why do people so reliably assume that their expertise in one domain — let’s say, weightlifting — gives them the ability to comment on another, wildly different domain like climate science? [3]

The easy explanation is that weightlifters are meatheads, but I don’t think that’s it. [4]

Let’s look at another telling example, someone who cannot be dismissed as a meathead. If you have spent any time at all in the online self-improvement space, you have run into Andrew Huberman. A scientist, a Stanford professor, a weightlifter and runner; chisel-jawed, muscle-bound, blue-eyed; this gleefully earnest podcaster and video-maker boasts subscribers in the millions. Huberman is — or at least appeared to be — one of those cases of nominative determinism so egregious that if he was a character in your draft novel or screenplay you’d get a strongly-worded email from an editor. “So this professor guy, he’s good at everything? And extremely good-looking? Runs marathons, lifts heavy weights? And you put “Uberman” right in his name? Yeah, I’m going to need to get you to revise that draft.” Huberman’s style is simple, and instantly identifiable: his Huberman Lab show consists of really long recordings, sometimes with guests, often without, always with a camera on. He doesn’t talk down to the audience, or at least, he affects not to; you feel like you’re an undergrad in an introductory university science class being enlightened via bewilderment. Huberman endorses free, science-based “protocols” for a wide variety of things — eating, sleeping, exercise, fertility — as well as a dizzying array of supplements, beginning with the podcast staple Athletic Greens and multiplying from there. In addition to the red flags raised by supplement-hucking, recent revelations have both asked and answered questions about Huberman’s character, as well as just how scientific many of his protocols and podcasts really are.

In short, the “lab” part of “Huberman Lab” is at best a stretch and at worst a fiction; his supplement regimen is spurious, some of his claims are implausible, others are bunk, and he was, until recently — there’s no polite way to put this — boinking five different women. If the boinking had occurred in just one time and place I’d have no other comment apart from praising his stamina, but as it turns out, it was just boring old-fashioned non-consensual cheating. At least one of the women interviewed claims he gave her HPV; another says he was prone to outbursts of rage.

None of these things speak well of Huberman’s character, and they’re opposite to his image as a very cool and together guy, but I’m almost equally bothered by the revelations that he strayed almost as far out of his lane as the Starting Strength guys. It doesn’t take much to start seeing this pattern repeat everywhere: well-meaning people begin opining on their area of expertise, which quickly grows to encompass everything. As well as sounding endless klaxons in my own head – I am swimming in the same sea with my little self-improvement newsletter – I’m struck by how difficult it is not just to produce accurate information but to consume it. How can we know what’s true or helpful?

This is where I risk going wildly wrong myself, but here’s how I try to manage it. As is eternally the case, your mileage may vary.

No gods, no heroes, no gurus

If you’re looking for information, and a high-profile person is providing both helpful and unhelpful content, this is easier to parse if you haven’t been worshipping at the altar of a cult of personality. Hopefully, you can take whatever useful stuff they’ve produced without feeling that you must either publicly defend or defenestrate them. The same applies for me, in the unlikely event that anyone feels like putting me on a pedestal. I often worry that my occasional ability to make England word good will result in people taking me too seriously. Try not to. This will not do wonders for my following or reputation as a producer of “content,” as everyone in the space seems to thrive on delivering every word with the same total sense of self-assurance, but I think it very important that you take what I say with a nutritionally correct amount of salt. I try my best to get things right but I’m inevitably going to get stuff wrong. When I do, I’ll try to correct it after the fact.

Domain expertise only

This might the most helpful way to map around the problematic. Here is an example: Is it 1976, and is Richard Dawkins talking about evolutionary biology? Then you should probably listen. Is he talking about trans people on Twitter in the 2020s? Good news, he’s so far out of his domain that he may as well be a fish on the Moon. You can safely ignore his pronouncements on trans folk, and much else besides. Hooray!

It doesn’t follow that expertise in one area can’t apply to others. And there are methods of inquiry that can throw up insights across multiple domains. Done properly, journalism is one of them. (If it wasn’t, I should probably stop writing this newsletter.) But if someone is being a dingbat in public then you’ve got a heuristic to hand: are they being a dingbat about their domain, or about something else? By way of example: Andrew Huberman is an ophthalmologist and a neuroscientist. In the event I find myself very interested in optic nerves, I will listen to him with reverence. The Starting Strength guys are very good at lifting weights. I’m happy to take their advice on my squat form, but I can safely leave their opinions on climate change in the trash where they belong.

Don’t be Rick

I’m an sometime fan of the show Rick and Morty, which is a reluctant admission because have you looked at that show’s fanbase? The premise, for anyone unfamiliar, is a kind of warped, multiversal Back to the Future in which Morty is a mostly inept teenage kid (and a bit of a piece of shit) and Rick is a autodidactic genius (and a complete piece of shit). The problem, as I see it, is that fans have not only taken “how to behave in real life” lessons from a cartoon, always a bad idea[5], but also that they’ve settled on being a know-it-all-asshole as a prerequisite to being an autodidactic genius. Needless to say, it’s not — or, at least, it doesn’t work that way around. There have been plenty of geniuses who were complete dicks in their personal lives, but their lesson should be that being an asshole is completely optional. Of course, being an asshole it doesn’t necessarily diminish domain expertise. I’ll happily accept drumming lessons from Ginger Baker or painting tips from Picasso, but I’m not going to take life advice from either.

How much information do you really need?

When you get interested in something, in self-improvement or any other field, it’s natural to want more information. But how much of it is necessary to what you want to achieve? I’m not telling any budding neurosurgeons to throw out their textbooks, please don’t do that, but in the self-improvement field a lot of information boils down to “do something quite simple very consistently for a long time.” Starting Strength teaches you how to squat, deadlift, bench, and press. If you are most people, this is much of what you need to know for the first stages of your lifting journey. Yes, one size doesn’t fit all, and I’m sure there are more optimal programs, but the fact remains that if someone who doesn’t lift starts to do so regularly and safely they’ll get stronger. [6] And that’s all the information a beginner needs!

One might quibble this attitude when it comes to Andrew Huberman. His entire thing is providing the research and background that (sometimes!) backs up his protocols, and surely that’s enough reason to listen. But let’s look a little closer at the protocols themselves. They are often very simple, which is no bad thing. In fact, routines.club — a truly hideous website that appears to be almost entirely an artefact of AI built to SEO-huck the same supplements as Huberman — has conveniently summarised Huberman’s daily routines, illustrated with physiologically implausible AI illustrations.

I’ll go one step further and deconstruct AI Huberman’s routine down to a bulleted list:

- Wake up at 6 am

- Drink 2 glasses of water + huck a supplement, also at 6 am

- Yoga Nidra meditation, also somehow at 6 am

- 6:45 am: sun exposure. I’m going to call this “going outside”

- 7 am: “cold exposure.”

- 7:30 am: workout

- 10 am: coffee

- 1 pm: breakfast(!)

- 3 pm: more Yoga Nidra

- 6:30 pm: cardio

- 7 pm: food

- 9:30 pm: dims lights for quiet time

- 10:00 pm: reading

- 10:30 pm: zzzz

Apart from the intermittent fasting, there’s nothing particularly controversial there. It’s a well-ordered day, if a highly idealistic one (anyone with children, chores, or a normal job will be able to spot this instantly.) The one remaining Huberman oddity is his insistence on “delayed caffeine intake” to about 90 minutes after waking up to avoid a crash later in the day, which a recent literature review has all but debunked. There’s certainly nothing that requires listening to hours of podcasts. Speaking of info-dumps: I’m going to suggest that Huberman’s podcast-lectures are not actually that well-formatted for those with a casual interest in science. On multiple listens, his style starts to resemble a Gish Gallop, an unending cavalcade of information and citations in which it’s very difficult for either scientists or laypeople to distinguish the science from the supplement sales pitch. (This podcast is brought to you by Mathletic Greens, the only balanced nutritional supplement that supports and enhances your maths skills). So not only is some proportion of the information suspect, it’s surplus to requirements.

In fact, over my long history of trying and failing to be consistent with anything self-improvement, I’ve come to suspect that all the extra information gets in the way. We labour under the delusion that more information — or information delivered in a slightly different package — is what we need, when what we really require is the ability to stop overthinking, simplify the more-than-adequate information we already have, and put it into consistent practice.

If I ever figure that out, I’ll let you know.

-

The weight-lifting program I (very imperfectly) use is essentially Casey Johnston’s LIFTOFF, which – as far as I can tell – shares a bit with Starting Strength, including some newbie-friendly tweaks. If all of that means nothing to you, don’t worry. I do recommend checking out Casey Johnston, though. She’s great. ↩︎

-

Before anyone decides to point it out: You shouldn’t really use noise-cancelling headphones as earmuffs. You should use earmuffs. But my mower is electric, and sounds more like a content swarm of bees than the usual deafening four-stroke roar, so I’m sure it’s not doing me any harm. What? What’s that? Sorry, I think some kind of bell that never stops ringing is calling me. ↩︎

-

Any neoliberal economists reading this can leave now, secure in the knowledge that your expertise is indeed applicable to every facet of life, as you’ve long suspected. ↩︎

-

And yet there’s probably something to it. If I’d looked a bit closer at Mark Rippetoe’s YouTube content before embarking on his podcast I might have come to the meathead conclusion a bit sooner and avoided the whole debacle: his omnipresent desk ornaments include a toy monkey and an oversized novelty mug with tits. ↩︎

-

When I was about eight I based an uncomfortably large part of my personality on Garfield comics. The autism is more and more obvious in retrospect. ↩︎

-

You also have to eat enough food with adequate protein, but that’s another story that others are probably better equipped to tell. ↩︎

Sign up for The Cynic’s Guide To Self-Improvement

A skeptical dive into the weird, sketchy, cringey, occasionally inspirational and life-changing world of self-improvement.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Are New Year’s resolutions doomed to fail?

You’ll have no doubt heard that only a small percentage of people who make a New Year’s resolution manage to keep it. It’s a piece of pop dicta, repeated endlessly in the period just before December 31 by media in desperate need of an easy factoid to recirculate for clicks. And debunking popular notions like New Year’s Resolutions sure does get clicks. Here’s an extract from a typical article, from the venerable Time:

And yet, by some estimates, as many as 80% of people fail to keep their New Year’s resolutions by February. Only 8% of people stick with them the entire year.

This depressing factoid has lived rent-free in my head with a bunch of others, like an anarchist squatter commune of bad vibes. If true, there’s an high chance you’re half-way to quitting whatever it is you resolved to do by now. I thought about writing an article about it, but I didn’t feel like dancing on the graves of people’s New Year hopes and dreams. Because as much as we tell ourselves ‘“it’s just another day,” it’s not, is it? The cultural gravity of New Year is, for Westerners, as inescapable as a black hole. And how could I write an article on how most resolutions fail, when the proof that they don’t always is right in front of us?

I’ll level with you. This article was originally inspired by seeing the above image in an Instagram story, upon which I Googled it, and found this Daily Dot article, in which the author says:

Most people give up on the resolutions about 10 days in. Instead, O’Donnell appears to have accomplished hers.

Classic internet “it’s funny cos it’s mean” snark, worthy of Gawker circa 2009, right? But the claim – perhaps because it was associated with an image of a pro-gun person who literally shot themselves in the foot — stayed in my mind, limping into my mental commune of received wisdom. I’d heard it so many times before. It has to be true, right?

Because this isn’t the Wide-Eyed Eternal Optimist’s Guide To Self Improvement, you’ll have guessed where I’m going with this:

The suggestion that only 8 percent of people ever achieve their resolutions, or that as many as 80 percent fail to keep resolutions by February, or that “most people give up on the resolutions about 10 days in” is bunk.

The first clue was clicking on the link in “by some estimates, as many as 80% of people fail” led not to a scholarly paper but another webpage, and clicking on the sources cited in that page and subsequent pages ended up with a dead link. That alone wouldn’t clinch it. What did, though, was that searching for “new year’s resolutions” and similar phrases in Google Scholar didn’t turn up any kind of widely-cited statistic around resolution success or failure. Like so much else in psychology, the truth is harder to pin down than self-improvement pop science might have you think. Nor are “success” and “failure” binaries, in the context of resolutions. A 2020 PhD thesis on NY resolutions by Hannah Moshontz de la Rocha, a student in the Psychology and Neuroscience in the Graduate School of Duke University, found that:

Goals varied greatly in their content, properties, and outcomes. Contrary to theory, many resolutions were neither successful nor unsuccessful, but instead were still being pursued or were on hold at the end of the year. Across both studies, the three most common resolution outcomes at the end of the year were achievement (estimates ranged from 20% to 40%), continued pursuit (32% to 60%) and pursuit put on hold (15% to 21%). Other outcomes (e.g., deliberate disengagement) were rare (<1% to 3%).

Those figures are… pretty good, actually? 20 to 40 percent of people achieving their goal by year’s end is a lot better than the pessimistic received wisdom that most people give up by February.

Likewise, a user at Skeptic’s Stack Exchange has done the legwork on the claim that only 8 percent ever achieve their resolutions, and found it to be at best misunderstood and at worst wildly cherry-picked:

The real source of the 8% number appears to be a survey conducted by Stephen Shapiro, a management consultant, author, and speaker, and published in an article on his website. According to him,

Only 8% of people are always successful in achieving their resolutions. 19% achieve their resolutions every other year. 49% have infrequent success. 24% (one in four people) NEVER succeed and have failed on every resolution every year. That means that 3 out of 4 people almost never succeed.

Of course, “Only 8% of people are always successful in achieving their resolutions” is not the same as “8% of People Achieve Their New Year’s Resolutions”. The study by Shapiro has not been published in a scientific journal.

Thanks, Stephen! Your literally incredible claim has poisoned a huge swathe of the internet when it comes to New Year’s resolutions, and (this is my own conjecture) led to a kind of low-key seasonally affective depression amongst those of us who’d like to make a lifestyle change around a culturally auspicious date.

If you’re in that cohort, rest easy. The takeaway is pretty clear: if you want to make a New Year’s resolution, feel free to. You may as well! The achievement/still working on it/still pursuing it statistics seem perfectly acceptable to me: clearly there’s some weight to the things. And it’s not too late: I unscientifically consider the “New Year” period to occupy the whole month of January, because that’s the span in which the year still feels new. I could add some stuff about setting SMART goals, or just making sure that your progress is in some way measurable, but that would be very boring and like every other article on the topic and is something you (an intellectual) probably already knew.

So I’ll just put in some potential resolutions you’ll hopefully have no trouble keeping.

Resolve not to start going to the gym in January

Look, just don’t. Especially if you’ve never gone before. There is much to be gained from lifting weights, including (obviously) muscle, but in my experience the gym in January is a Bad Time. Everyone who made a resolution to “go to the gym more” is there, hogging the machines or giving themselves renal failure from trying to deadlift too much, sweating and grunting and selfie-ing. It’s not worth it.

If you’re a regular, you might choose to power through it, but if you’re a total newbie, save the money on gym fees and buy a broomstick. It’s not a witch thing and I’m not joking. You want to learn how to lift weights before you lift any actual weight, and here the incredible Swole Woman, Casey Johnston, has you covered.

Resolve not to “lose weight”

This isn’t my area of expertise, but I’ve listened to enough people for whom it is to know that “losing weight” purely for the sake of losing weight is — for the vast majority of people — a toxic concept that can easily ruin lives. Food is good, you need it to live, and as a general rule if you’re exercising you need to be fuelling yourself properly. There are plenty of people who know better than me on this so I’m just going to recommend Casey Johnston again.

Resolve not to “do something every day” unless it’s very automatic or very low effort

You can’t move without this shit. “Go to the gym every day.” “Do X push-ups every day.” “Practice Y every day,” or my personal bugbear that I can’t swear off swearing to do: “do art every day.” So let me draw a line in the sane for myself and possibly you too: can we not? Unless it’s for something like “drink water,” or “poop,” committing to do something every day seems a fast track to the kind of demoralizing failure that only comes with overcommitment.

Take “Gym every day.” A moment’s critical reflection will reveal this goal to be both wildly improbable and useless. You’re going to get crook. You’re going to have a family thing come up. You’re going to get a flat tire. At some point, the gym will be inconveniently closed. Letting any of these all-but-inevitable and entirely reasonable life events ruin your resolution because you didn’t tick off all 365 days in the year isn’t worth it. A vanishingly small subset of people either need to go to the gym every day (actors, bodybuilders, influencers in the field of same) or will get any tangible benefit from doing so. For nearly everyone else, working out daily is a fast track to ruined health, because you’re not taking vital recovery time. Your Average Joe, including very much me, will do better resolving to “go to the gym several times a week, with at least a day’s rest in between sessions, and obviously not when sick” or something similar.

The same applies to art. Long, bitter experience teaches that if you try arting every damn day you’ll start hating art and everything adjacent to it. Of course there are exceptions to this rule, and if you’re one of those people who can do something out of the ordinary every day, more power to you — but all I’m aiming for this year is mostly consistent consistency.

Resolve not to get your New Year’s resolution effectiveness information from websites that don’t cite their sources, or management consultants

You probably didn’t need me to tell you that.

Here’s a watercolour seascape I did, because I needed an illustration for the newsletter’s thumbnail image. Thanks for reading. This newsletter likely won’t be on Substack much longer, due to their cataclysmically awful handling of an entirely self-inflicted Nazi/TERF/active disinformation ecosystem controversy, and (less importantly) the fact that they’d rather dabble in AI bollocks than offer basic email composition features like a native spell-checker. In short: it’s them, hi, they’re the problem, it’s them. Barring a policy u-turn, and a spell-checker, chances are I’ll move it to another provider in the next few weeks. If you do subscribe here, either free or paid, don’t worry. You shouldn’t see much of a difference, and I’ll be choosing a platform that enables comments so our discussions remain as fun and enlightening as they’ve been here.

In the meantime, comment away! It’s great to have you here in 2024. It’s only the 12th of January, and it feels like a whole year already.

Why is Stuff promoting right-wing propaganda?

The way New Zealand’s Taxpayers’ Union works should be obvious by now. This fake union — which is actually a neoliberal, ultra-capitalist lobby group acting in concert with a dense network of international right-wing think tanks called the Atlas Network — advances its agenda by carefully picking divisive issues and laundering them through the news media. Every story they land in a mainstream publication is a victory for them, and thanks to the news media’s addiction to conflict and its diminishment by market forces, the fake union and its think-tank bedfellows are having an easier ride than ever.

It probably shouldn’t be this easy, though. Witness this glorified press release masquerading as a story in Stuff, published on Christmas Eve, in the heart of the silly season:

Merry Christmas, council workers! Your present this year is the Taxpayers’ Union talking about how you should be sacked, via the increasingly beleaguered Stuff, which has just disestablished much of its investigative journalism team. The story itself is… boring. The first bit is based squarely on (via what looks some heroic paraphrasing to avoid outright copying) a Taxpayers’ Union press release. The fact that some council staff earn over $100,000 is framed as shocking, when in fact it’s wildly unsurprising; the people who run cities and towns are doing a demanding job and they’re (sometimes) paid well for it. And that’s what the article itself says, a third of the way through, citing Infometrics (an economic consultancy based in Wellington.)

Infometrics chief forecaster Gareth Kiernan said he would expect roles in larger councils to be paid more than equivalent roles in smaller councils, particularly at the higher levels.

Near the end comes a missive from Connor Molloy, Campaign Manager for the Taxpayers’ Union (who are not identified in the story as anything other than “the Taxpayers’ Union,” with no explanation for readers that the “union” is a right-wing lobby group.) Molloy, of course, seems to think that the best Christmas present for council staff is for them to lose their jobs:

Connor Molloy, campaigns manager for the Taxpayers’ Union, said reducing the number of highly-paid “backroom” staff was the right thing to do if councils were threatening big rate hikes.

“Rather than going straight for core services like rubbish collection and libraries, councils ought to look inwards at their own bloated bureaucracies first when looking to make savings.

From a quick scan, this story seems like merely another example of the TPU successfully “placing” a piece of its neoliberal propaganda in the media, which happens — to the media’s vast detriment — all the time. But on a closer look, things get even bleaker.

Reading the story, a little blue hyperlink in the opening paragraph caught my eye, as it’s designed to do.

Curious! I wanted, as many readers might, to see the raw data informing the story. I was mystified as to why Stuff weren’t just hosting it themselves, or embedding the data on their page, as is standard practice for news organisations, which just made me curiouser.

I clicked through.

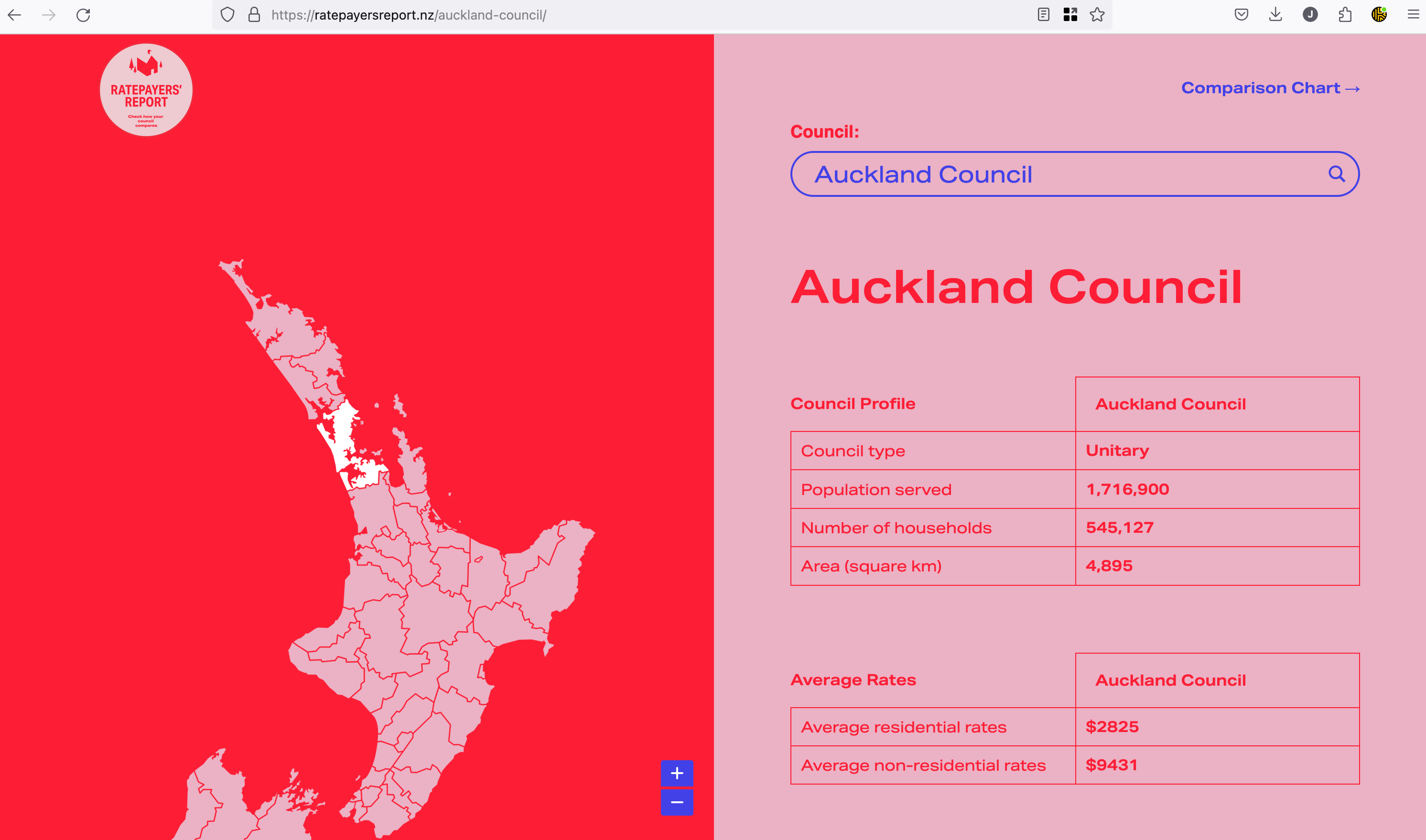

The page I landed on looks like this.

Hmm. Looks like I just need to put my email address in this handy form and I’ll get to see the report! You can even choose to be one of the three types of person: an “Elected official,” “Ratepayer,” or “Journalist (or reseracher.)1”

I’ll just pop my details in and click “VIEW REPORT” and…huh? It’s just a normal webpage! No need for an email address at all!

Look at that URL. That’s not a hidden or gated page: if the website was designed to be user-friendly, you could navigate straight to it. You don’t need to put in an email address to access the data, but the page is designed explicitly to make it seem like you do.

Do you at least get emailed the report? Like hell. Nothing shows up in your inbox until a few days later, when a horrifically-formatted email arrives and it’s made clear you’ve been added to a Taxpayers’ Union mailing list.

Take another look at that first form up there. There’s nothing whatsoever to indicate that you’re signing up to a mailing list. Not even a pre-checked “yes, send me Taxpayers’ Union emails,” checkbox. It’s either very poorly designed or deliberately misleading: either way, it could easily be illegal, under New Zealand’s Unsolicited Electronic Messages Act (2007).

So this is where we’re at. Stuff isn’t just parroting Taxpayers’ Union propaganda and enthusiastically leaning in to their “government = waste = fire them all” framing; they’re encouraging their readers to visit a website that harvests their emails and, unasked, signs them up for the full TPU package.

If you’re thinking “this seems bad!” well, I have more: want to know where this overtly propagandistic Ratepayers’ Report that shills for a right-wing lobby group originally comes from?

It was born as a collaboration between Stuff and the Taxpayers’ Union.

Don’t take my word for it: here’s the TPU press release.

The New Zealand Taxpayers’ Union, in collaboration with Fairfax Media has today launched “Ratepayers’ Report” hosted by Stuff.co.nz (…) “For the first time, New Zealanders now have an interactive online tool to compare their local council to those of the rest of the country,” says Jordan Williams, Executive Director of the Taxpayers’ Union. “Ratepayers can visit ratepayersreport.co.nz to compare their local council including average rates, debt per ratepayer and even CEO salaries.”

That was back in 2014. But at least the 2014 Ratepayers Report was hosted on Stuff’s own site, and didn’t speciously sign its users up to spam. It looked like this:

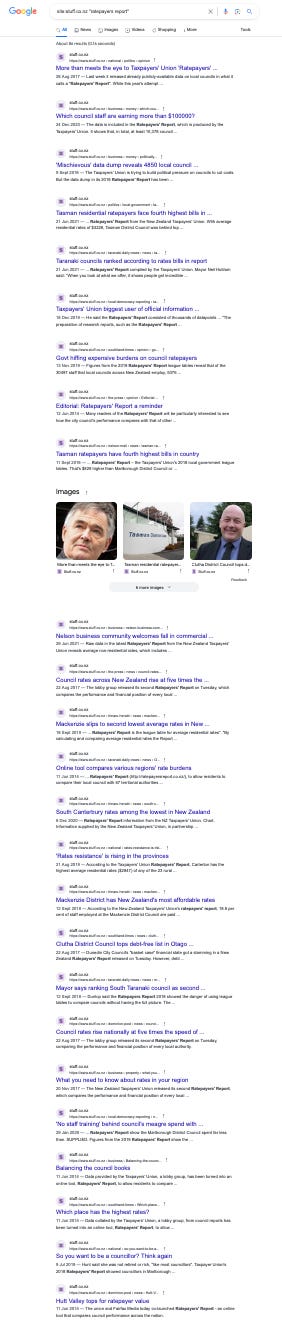

Nearly a decade later, the Ratepayers’ Report, together with a payload of TPU propaganda, is embedded in news cycles. The Taxpayers’ Union puts it out regularly, and media publish obligingly. A Google search of the Stuff site for “Ratepayers’ Report” shows you how entrenched it is.

This is how the Atlas Network right-wing sausage factory works: their junk “think tanks” propagate their neoliberal message and exploit the decline of media by doing journalists’ work for them. They’ve been doing it for years, and it’s been wildly successful, to the point that they’ve just released a book skiting about how manipulative they are. But this — a reputable news site sending its readers to sign up directly, and probably unknowingly, for TPU propaganda — seemed beyond the pale. What was going on? I wanted to know, so I put the following questions to Stuff.

- Why is Stuff linking to a Taxpayers’ Union email harvesting site?

- Was Stuff aware that the function of the Ratepayer’s Report was at least partially to harvest emails for the Taxpayers’ Union?

- What is Stuff’s policy on linking to external sites, especially those that may act maliciously or harvest user details?

- In your view, was the nature of the Ratepayer’s Report website (and its email-harvesting capability) sufficiently disclosed to readers?

- What is the present nature of the relationship between Stuff and the Taxpayers’ Union?

- Referring to the press release above, what is the past nature of the relationship between Stuff and the Taxpayers’ Union?

- Was this a commercial relationship, i.e. did either TPU or Stuff pay each other for participation in the Ratepayer’s Report? Was there contra, or an exchange of services?

- Does the relationship between Stuff and the TPU that established the Ratepayer’s Report persist today?

- If not, when did it end, and why did it end?

- Does Stuff have guidelines for journalists (or editors) who utilise the work of lobby groups in their stories, perhaps along the lines of the BBC? I refer to this page, which states:

Contributors’ Affiliations

4.3.12 We should not automatically assume that contributors from other organisations (such as academics, journalists, researchers and representatives of charities and think-tanks) are unbiased. Appropriate information about their affiliations, funding and particular viewpoints should be made available to the audience, when relevant to the context.

If so, can you please provide me or point me to a copy of these guidelines?

Further to the above question, why does the story not identify for readers who the Taxpayers’ Union is, and what their work entails? I refer to these Newsroom stories that make it clear that the TPU is a neoliberal, right-wing lobby group, with links to fossil fuel and tobacco concerns, as well as being part of the international Atlas Network of neoliberal, right-wing think-tanks.

I note also that this Stuff story (correctly) identifies the Taxpayers’ Union as a “right-wing pressure group,” so clearly it’s possible to be upfront about the group and their motivations when writing a story about the TPU’s work and the concerns they raise. Given this, why isn’t this clear identification the norm across Stuff?

A day later, Stuff replied, with a comment they asked to be attributed to Keith Lynch, Editor-in-Chief of Stuff Digital:

Stuff has no formal relationship with the Taxpayer’s Union. A report from the Taxpayers Union was transparently quoted in the story alongside information from other named sources. In this case, the link to the source was included so audiences could access the information referenced in the story, should they wish.

On reflection, we have now updated the story to remove the link.

There you go, Stuff readers: four sentences and one middle finger. Wondering why Stuff saw fit to partner with the TPU? When the partnership ended? Why it ended? What their guidelines are when handling the journalistic equivalent of radioactive waste — the propaganda created by think tanks to shape society in their image? Screw you. You don’t get to know. The hyperlink to the Taxpayers’ Union site that misleadingly harvests readers’ emails is gone (without so much as an edit notice or correction on the page) because it should never have been there in the first place — but as for the merest whisper of explanation as to why the TPU so often gets such an easy ride in media?

Nothing.

I replied, asking Stuff if they’d be giving my other questions actual answers. I didn’t hear back. It’s amazing, really: journalists hound politicians endlessly to just Answer The Question (as they should!), but when it’s them on the hook they provide weasel words that’d do any politician proud, and then evaporate into the ether.

Going back to the Stuff story one last time, I saw this little banner above the body copy.

You care about our money? I bet you do. Here’s a thought, Stuff: how about showing that you care about your audience? Stop feeding them repurposed think-tank propaganda, own your mistakes, and act with integrity. Perhaps, instead of taking the Taxpayers’ Union at their obviously-compromised word, you could talk about how the TPU used racist insinuations about “co-governance” to fight Three Waters, a government program designed to fix horrifically neglected water infrastructure while freeing councils from paying for it — the repeal of which is now being cited by councils as a key reason for massive rate hikes.

Maybe then people would be more inclined to pay you, instead of mistrusting you.

In a world where misinformation is so easily spread, the mainstream press should be fighting it, not amplifying it. It’s too bad that Stuff seems incapable of assuring its readers that it will treat think-tank content with the caution it warrants.

-

Sic. ↩

A Simple Nullity

An incredibly important documentary went live today, and I don’t want you to miss it.

“Trick or Treaty? Indigenous rights, referendums and the Treaty of Waitangi” is a deep dive on how right-wing influence networks in Australia joined forces to destroy Australia’s Indigenous Voice to Parliament — and how the same forces are at work in New Zealand. I’ve taken an interest in New Zealand’s gaggle of lobby groups for a long time now, so I was very pleased to do research for the doco and work with award-winning producers and top-tier journos Mihingarangi Forbes and Annabelle Lee-Mather. I also appear on camera, which is less my thing, but as an Aussie-born Kiwi the subject is very close to my heart, and I didn’t want to miss the chance to tell what I think is a vital story.

Much of what’s in the doco is far from secret, particularly to those in the media-politics confluence; but (crucially) it is not well known by the general public. The short version is that there are a bunch of well-funded, right-wing, neoliberal influence and lobbying groups in New Zealand, who share links with similar groups overseas. They are ostensibly independent groups, but they coordinate their activities, share resources, trade personnel, and — when you zoom out slightly — essentially work as one large body. In fact, several of the groups officially operate under the auspices of one giant neoliberal anthill organisation, called the Atlas Network. In New Zealand, these groups — and the individuals who work in them — tend to cluster around parties like ACT, NZ First, and National. Their modus operandi is to write stultifyingly dull papers, create model legislation, get pet MPs and parties elected, and incessantly insert their messaging into the public consciousness via the media. That messaging varies from group to group, but the (almost invariable) common denominator is this:

They consistently oppose both climate action and recognition of indigenous rights.1

Having seen extraordinary success in Australia with the triumph of the “No” vote on the Voice, these same forces look to be coming for Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Since it gained limited judicial and legislative recognition, Te Tiriti has been a bugbear for neoliberals. It represents everything they hate: an example of collective recognition and responsibility, and an admission that indigenous people do in fact have continuing inalienable rights that pre-date colonisation. Perhaps most importantly, Te Tiriti acts as a potential handbrake on the kind of unfettered property rights required for mining and fossil fuel companies to prosper.

So it’s no surprise that the ACT Party and lobbyist enablers like Hobson’s Pledge want nothing more than to get rid of it.

Wherefore referendum

In the doco, I’m asked if I think there will be a referendum on Te Tiriti. My answer is yes: in my opinion, it only really remains to be seen what form the referendum will take. There are two options: a government-initiated referendum or a citizens-initiated referendum. For the first option: the coalition agreement between National and ACT specifically calls for ACT’s Treaty Principles Bill to be advanced to select committee: National have pointedly not committed to a referendum but to ACT Party leader David Seymour, it’s clearly still on the cards.

The other option is a citizen’s initiated referendum or CIR: anti-Tiriti group Hobson’s Pledge, co-founded by former ACT Party leader Don Brash, is already lobbying for one. Anyone can get a CIR before Parliament; all that’s required is the signatures of ten percent of registered voters. For an issue like Te Tiriti, long a lightning rod for cranks, racists, and the terminally uninformed, 370,000-ish signatures should be a snap.

In my opinion, either option stands a very real risk of ripping the country apart, on a scale not seen since the Springbok tour protests or perhaps even the Land Wars. And I also think that ACT’s proposed Treaty principles — on top of the other anti-Tiriti measures being undertaken by the ACT/NZ First/National government — would be the most profound assault on indigenous rights in Aotearoa since the racist Justice James Prendergast declared the Treaty a “simple nullity.”

Maps of Meaning

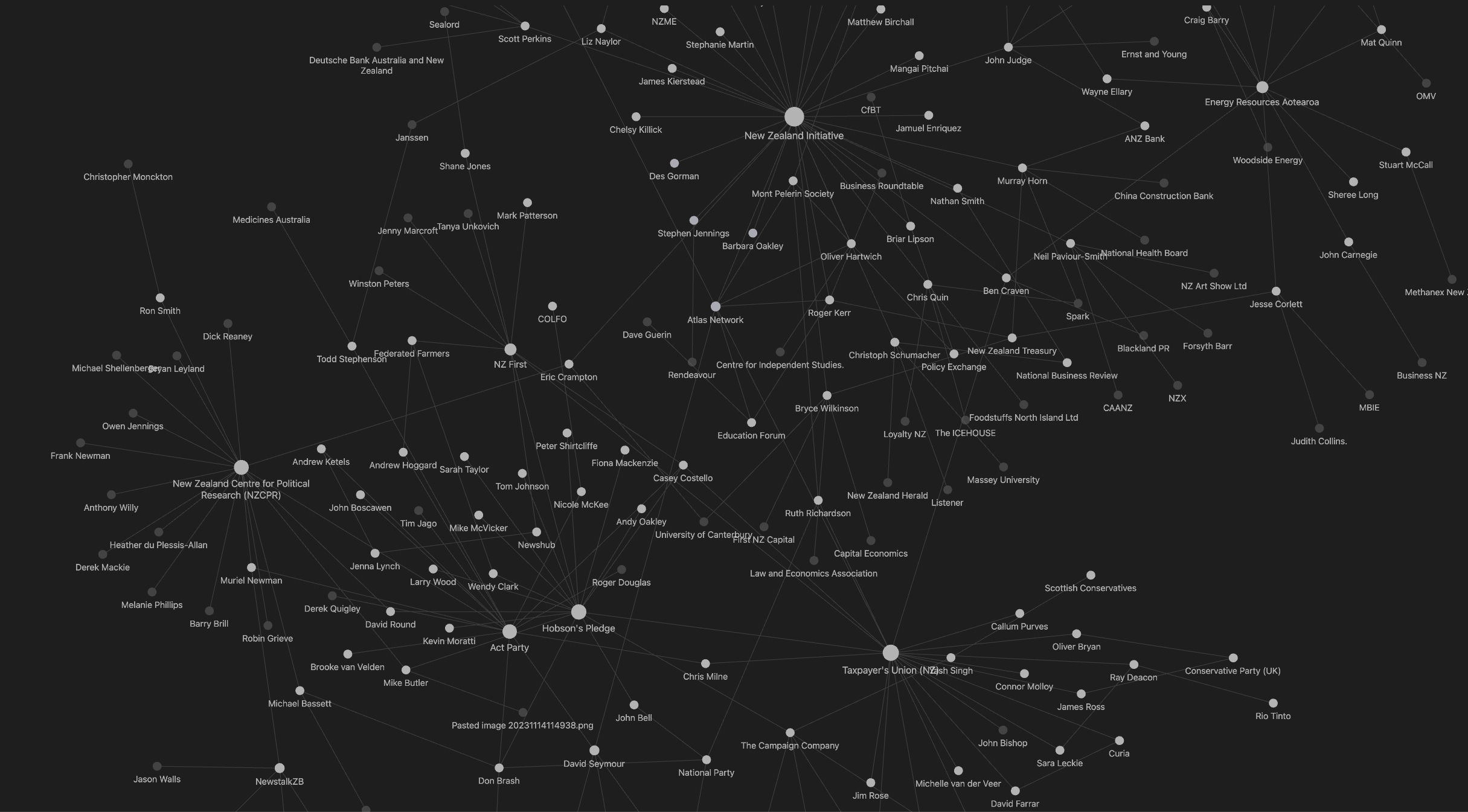

In the doco, there are a few shots of me using a program that looks like a digital spiderweb. I like that it’s been included, because it’s becoming a big part of my writing process. Obsidian is a note-taking program that allows users to write in Markdown, and easily link notes to each other. I’d recommend it to journalists everywhere — it’s encrypted, open-source, and great for brain-dumping and research. One of its nifty features is its mind map or “graph view,” functionality, which showcases all your notes and how they link to each other.

That, I’m very aware, is essentially a computer version of this:

Mind maps have a bad name, thanks to conspiracy theorists and very funny sketches based on conspiracist antics, but they’re a really useful visual tool for research. What’s obvious on viewing the mind map I’ve made — which, to be clear, is comprised primarily of publicly-available information listed on the websites of the organisations I’m researching — is just how entwined everybody is. New Zealand is a small country, to be sure, but after a few hours it becomes very clear that the favourite hobby of these lobby organisations is giving each other jobs. The boards are stacked with fixtures of the “business community” — the very elites that these same organisations so often rail against — and a scan of member’s employment histories often reveals them bouncing around related orgs like pinballs. New NZ First MP Casey Costello, to pick one name more or less at random, has previously worked for (or with) the Taxpayer’s Union, Hobson’s Pledge, and ACT. Each organisation is so entwined with the others that they start to look, accurately, like the same body.

The media is the message

One of the best things about this documentary is that it gives New Zealanders something Australians missed out on: a primer on who these interconnected neoliberal groups are and how they operate. While they have many channels to their audience, like newsletters and social media, the most important medium is still the mainstream media. One of the things I said during shooting that didn’t make the final cut is that the New Zealand media is “infected with lobbyists” — and it is. Lobbyists and their ilk advance their agenda in the media through the following methods:

- Giving journalists their phone numbers and never failing, as I mention in the doco, to pick up when it rings, to deliver some variation on “the world’s richest and most sociopathic people are right, actually.”

- Combining a never-ending deluge of press releases with juicy scoops and leaks of the “ya didn’t hear it from me but boy have I gotta story for YOU. You’ll never guess how much funding this poet got!” variety, usually supplied to pet journalists and right-wing media orgs who can be relied upon to advance the lobbyist’s agenda. See also: Newstalk ZB.

- Providing enticingly conflict-loaded “insider” opinions for free or very cheap to cash-strapped editors and producers, with the tangible result that a huge proportion of New Zealand’s opinion columnists, podcasters, and other varieties of talking head are paid lobbyists of some kind, which brings me to:

- Getting actual media jobs, which has everything to do with a laissez-faire media culture that pretends not to notice the constantly revolving door at the axis of business, politics, and journalism. Numerous examples include New Zealand Institute asset Luke Malpass waltzing into the job of political editor at Stuff, a position he wields with all the impartiality of a used car salesman; ex-National leader Simon Bridges failing into a podcast at Stuff; New Zealand Institute sleep aid Eric Crampton’s spot at Newsroom; Muriel Newman (the founder of unhinged climate-denying lobby group NZCPR) being slung a new gig at Newstalk ZB; long-time right-wing lobbyist Matthew Hooton getting a seemingly eternal opinionist gig at NZME; and his (current? former? I don’t know, and neither do you, because the media outlets he appears on often don’t deign to tell us) consigliere Ben Thomas, who rejoices in the lifetime appointment of Chief Migraine Officer on the Spinoff’s exhausting political podcast, Gone By Lunchtime.

Given the noble Fourth Estate functions essentially as a base of operations for influence operators, what can be done? Lots, in my opinion:

-

Short of proper lobbying finance and influence disclosure law, which are all but impossible under the present Government but might be an option when they disintegrate, the media can start by voluntarily and transparently showcasing the bona fides of its talking heads. Every time a lobbyist shows up to generously peddle influence and build their own profile, their appearance can be marked with a disclaimer showing exactly who they have a.) previously worked for and b.) are working for now. That’s really the least that should be done: audiences desperately need to know which talking heads are on the take2.

-

News media can also choose to identify when stories have been shopped to them by members of astroturf influence organisations like the Taxpayer’s Union, or (more ideally) refuse to run their hit pieces.

-

Media should identify and label influence groups accurately: for example, identifying a spokesperson as being from the benign-sounding “New Zealand Institute” tells an audience nothing: labelling the New Zealand Institute (accurately) as a “neoliberal lobby group for ultra-free-market economics with representation from some of the biggest corporates in New Zealand on its board” tells audiences what they need to know.

-

Media should also proactively highlight when their employees are intimately linked to lobby groups or politicians, which is (especially in the Press Gallery) much more common than non-media people might think. Such is the case with Newshub’s Political Editor Jenna Lynch, who is married to ACT Party Chief of Staff Andrew Ketels. It doesn’t matter if she’s the world’s most scrupulous reporter who somehow manages never to discuss politics with her husband: it’s a very obvious potential conflict of interest, and audiences deserve to know about it — and any other such conflicts.

-

As a final suggestion, the media should also stop giving prime opinion and airwave real estate to the world’s most boring politicians because of the more-common-than-you think reasoning of “oh, they were such a hoot when we got on the piss that one time.” Their audiences will fervently thank them.

Thanks for checking out the documentary. Please share it far and wide: I think there’s a lot in there that New Zealanders both deserve and need to know.

-

The New Zealand Initiative hotly denies they are climate deniers, by pointing out that they accept the reality of climate change and that they support the Emissions Trading Scheme, but they also lobby stringently against any and all climate action that isn’t the ETS. This is easily understandable given the fact that that the ETS is set up as a literal licence for corporations to continue with carbon pollution, as well as a way for the rich to get richer trading in carbon credits. ↩

-

In this spirit of transparency, you should know that I was once a paid member of both the Civilian and the Green political parties. I was directly involved in neither organisation and my membership in the respective parties lapsed when it wound up and I forgot to pay my sub. From memory the total expenditure amounted to twenty-five bucks. ↩

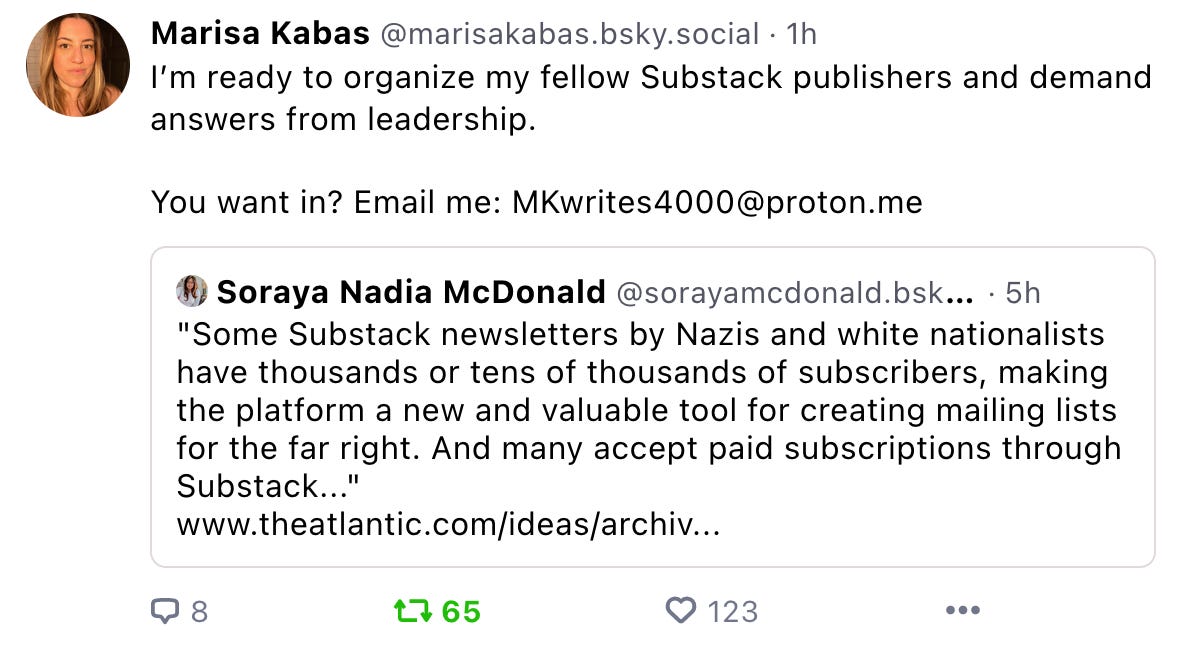

Substackers against Nazis

There’s a good chance you’ve seen the following letter a lot lately: I’ve been meaning to send it out for a while now. I’m sending it to recipients of both The Bad Newsletter and here on the Cynic’s Guide, because — to say shortly what I’ve said at length — having Nazis on your platform when you are not a free speech platform is bullshit. I could respect an absolutist free speech stance, but Substack is not a free speech platform. There are multiple forms of speech that are not accepted here, including sex work: try using Substack to send nudes or fire out some erotic fiction and see how long your account lasts. Still shorter version: Nazis yes, nudes no. And if you’re not going to be a true free speech platform, then I’m going to have to join the voices demanding that you get rid of the Nazis.

Of course, it goes further than Nazis, who are merely the tip of the Substack garbageberg: this place is a haven for hate and disinformation merchants of all kinds who are thrilled that Substack is giving them a platform and the ability to monetize. I’m putting a piece together on how Substack enables and encourages disinformation: look out for it soon at The Bad Newsletter.

Dear Chris, Hamish & Jairaj:

We’re asking a very simple question that has somehow been made complicated: Why are you platforming and monetizing Nazis?

According to a piece written by Substack publisher Jonathan M. Katz and published by The Atlantic on November 28, this platform has a Nazi problem:

“Some Substack newsletters by Nazis and white nationalists have thousands or tens of thousands of subscribers, making the platform a new and valuable tool for creating mailing lists for the far right. And many accept paid subscriptions through Substack, seemingly flouting terms of service that ban attempts to ‘publish content or fund initiatives that incite violence based on protected classes’…Substack, which takes a 10 percent cut of subscription revenue, makes money when readers pay for Nazi newsletters.”

As Patrick Casey, a leader of a now-defunct neo-Nazi group who is banned on nearly every other social platform except Substack, wrote on here in 2021: “I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling. The cause isn’t going anywhere.” Several Nazis and white supremacists including Richard Spencer not only have paid subscriptions turned on but have received Substack “Bestseller” badges, indicating that they are making at a minimum thousands of dollars a year.

From our perspective as Substack publishers, it is unfathomable that someone with a swastika avatar, who writes about “The Jewish question,” or who promotes Great Replacement Theory, could be given the tools to succeed on your platform. And yet you’ve been unable to adequately explain your position.

In the past you have defended your decision to platform bigotry by saying you “make decisions based on principles not PR” and “will stick to our hands-off approach to content moderation.” But there’s a difference between a hands-off approach and putting your thumb on the scale. We know you moderate some content, including spam sites and newsletters written by sex workers. Why do you choose to promote and allow the monetization of sites that traffic in white nationalism?

Your unwillingness to play by your own rules on this issue has already led to the announced departures of several prominent Substackers, including Rusty Foster and Helena Fitzgerald. They follow previous exoduses of writers, including Substack Pro recipient Grace Lavery and Jude Ellison S. Doyle, who left with similar concerns.

As journalist Casey Newton told his more than 166,000 Substack subscribers after Katz’s piece came out: “The correct number of newsletters using Nazi symbols that you host and profit from on your platform is zero.”

We, your publishers, want to hear from you on the official Substack newsletter. Is platforming Nazis part of your vision of success? Let us know—from there we can each decide if this is still where we want to be.

Signed,

Substackers Against Nazis

Shut Up To Succeed

There’s this skit at the opening of the Tenacious D song “Kielbasa” that starts with KG saying “Dude, we gotta fucken write something,” and because I got into the D at an impressionable age and the lyrics are burned into my hippocampus with letters of fire, I think of this song every damn time I’m behind on a deadline, which is most of the time. And yet I resisted writing this piece, for a few reasons.

One is that I’m spooked by success. A few years back, I did a tight five minutes at a comedy open mic. I’d done stand-up sets before, to varying results, including quite a lot of laughter and at least one obligatory crash and burn. This time I was determined to get it right and I did. I learned the material backwards, including a few alternative paths should a particular punchline flop, the crowd laughed their collective asses off and I left the stage on a high. “That was brilliant!” I thought. “I can’t wait to do that again,” and I never have.

The other reason I’ve been avoiding writing this particular piece is that I’m not sure that telling people about what I’m looking to achieve is a good idea. You may have heard, as many who’ve read self-help have, that you need to make your goals public, or tell people what you’re trying to achieve, for reasons of “accountability.” Many, including Tim Ferris, suggest publicly announcing your goal, or making a bet with a friend (if I don’t do X by Y, you get to keep $Z dollars.)1

The idea is that publicly announcing a goal will help hold you accountable. But, as is usual in the field of self-help, the advice is wildly conflicting. Many authors suggest telling no-one (or as few people as possible) about what your goal is or what you’re working on. According to numerous sources, some of them credible, telling people your goals can affect the likelihood of achieving them.

Naturally, I’ve just Googled the topic, and I’ve immediately hit someone taking the bit way too damn far, because that’s always how it goes in this ridiculous field. “Why telling your goals is a fatal mistake” screams one of the first Google hits. Fatal? Really? Unless the goal is “skydive without training” or “build an electric blanket from scratch” I doubt it’s going to be deadly, but let’s find out. The piece, which I nearly stopped reading in the second paragraph when it mentioned neuro-linguistic programming, is by a bloke called Peter Shallard. He describes himself as “a renowned business psychology expert and therapist gone renegade.” This last seems accurate: his “About” page contains no formal qualifications.

It suggests that if you tell people about what you’re up to, it can give you the same kind of mental reward as actually doing the thing you’re telling everyone about. Just because I’m cynical about Shallard’s qualifications doesn’t mean it’s all a load of rubbish, though. Other pieces by more credible authors — like Atomic Habits mega-seller James Clear — suggest the same effect.

If that’s right, it’s a bit cooked for me, because I have a newsletter that’s about all the different self-help shit that I do, and telling you about it may be dooming everything I try. Having an audience for my stuff hasn’t helped me achieve my big goal, which was to post regularly: if anything, it’s made it harder. Some people pay me actual money for this writing, others seem to like it enough to hang around for each epistle, and this frankly freaks me out a bit. I always worry that I’m disappointing you.

Fortunately, when you dig into the research it gets both vague and highly specific. Good science tends to come loaded with caveats, and the original paper that everyone references, by a bloke called Peter M Gollwitzer, is no exception. As you can read for yourself, the experiments in the study have a rather tangential connection to reality. They measured whether students would do stuff like “watch videotaped study sessions for slightly longer” or “compare yourself to variously-sized cartoons of lawyers and indicate which one you feel most similar to.”2

I’m not mocking this. It’s real science, the conclusions are both interesting and valuable, but they’re not necessarily broadly applicable to the real world. That never stops self-help writers from immediately making it so, though.

Where does that leave us? Is it a yeah or a nah on telling people about your goals? How about: why not both, or neither? I think the answer depends on what sort of person you are, or what kind of goal you have in mind. If you’re the sort of person who really needs others to give you a rev up, by all means tell a few specific people about what you’re trying to achieve. Or if you thrive on working on something in secret to surprise people later down the line, do that. Curiously, this approach gels with some of the research I mentioned above, which suggests that if your goal is founded in identity — “I wanna be a gym guy/gal/nonbinarino” — then telling people about it is likely to reduce the effectiveness of the goal. But if it’s founded in something more specific — “I wanna bench press 100 kilos” — then the identity condition might not apply, and perhaps it’ll be helpful to tell others or otherwise have people help you out.

All the above is my long-winded way of telling you that, somehow, I’ve managed to consistently go to the gym for a few months now.

Again, caveats. I am using the word “consistently” slightly outside of its conventional calibration. I’ve noted the date of each gym session since August, during which I managed to go a grand total of four times. In September I went three times, a 25 percent decline, but October picked up nicely with seven attendances. In November I went nine times, and so far in December I’ve managed to go every other day.

Improbably, I love it.

I can’t quite put my finger on what changed: the nearest thing I can compare it to is the same buzzy “I hate this, but I like it” feeling I get from taking cold showers — and I’ve been doing those for well over a year now. I’ve also refined my workout a bit: I followed a plan one of the gym trainers set me for a while, and now I’ve shifted to a strength-building workout that’s easy to understand, hard to master, and never stops getting harder.

The other reason I like the gym now is that it’s working. A while back I noticed that a bunch of my favourite t-shirts were getting too small. I’d definitely outgrown shirts before, usually around the tum region, but this was a bit different. They were pulling up at the shoulders and into my armpits. Never mind, they were going to holes anyway. I consigned them to the painting-rag box.

Then it started happening to younger shirts, and I couldn’t pretend that it was anything to do with the age of my shirts or our washing machine. I’ve got bigger, in a way I wanted and planned and worked to get bigger, and that is very satisfying. Much more importantly, the numbers on the Heavy Metal Things are going up, too. In August I was knocking around a 40 kilo bench press and drawing this not-smiley face next to it: 😐

Today, my best bench press is close to double my August numbers. The emoji has changed to this: 🤨

This isn’t the plan, but the meme is timeless so I made sure to include it. Back when I started this newsletter, I was using how many pull-ups I could(n’t) do as a success metric. I stopped updating progress because I was embarrassed the number wasn’t going up, which is what happens when you don’t, uh, work out. But I do now, and the numbers are in: I’m doing 20+ pull-ups in a given gym session — and that’s in between my other exercises. I’m pretty pleased with that. Pull-ups are hard. But it’s still early days. I have a specific and quite ambitious goal in mind for how much I’d like to be able to lift: the goal is to bench-press 100 kilos, and to be able to do a muscle-up, which is probably the most aptly-named callisthenic exercise in existence.

No-one except Louise and my t-shirts has noticed that I’m going to the gym, but I’d like to think that’s not why I’m going. I read once that, one day, you pick up your child for the last time, and — as an older dad — I want to delay that day for as long as possible. If I keep tracking the way I am now, I’ll still be able to yeet my boy Leo well into adulthood, and that’s exactly how I want it.

Hopefully telling you about it won’t stop it from happening.

I originally titled this newsletter “Harder, Better, Faster, Shorter” not just to get the Daft Punk song in your head but because it was meant to be shorter than normal. That hasn’t worked out, but oh well. Substack lets you do surveys, so I’ll pop this one here – I want to find out what kind of newsletter frequency you’re actually after here.

And, as usual, I look forward to chatting in the comments.

The Hand That Feeds

A short lunchtime post today. Let’s begin with a (gift) link to an Atlantic story revealing Substack’s Nazi problem. How bad is is it here? This bad:

At least 16 of the newsletters that I reviewed have overt Nazi symbols, including the swastika and the sonnenrad, in their logos or in prominent graphics. Andkon’s Reich Press, for example, calls itself “a National Socialist newsletter”; its logo shows Nazi banners on Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, and one recent post features a racist caricature of a Chinese person. A Substack called White-Papers, bearing the tagline “Your pro-White policy destination,” is one of several that openly promote the “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory that inspired deadly mass shootings at a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, synagogue; two Christchurch, New Zealand, mosques; an El Paso, Texas, Walmart; and a Buffalo, New York, supermarket. Other newsletters make prominent references to the “Jewish Question.” Several are run by nationally prominent white nationalists; at least four are run by organizers of the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia—including the rally’s most notorious organizer, Richard Spencer.

The rest of the article is just as damning. I am only annoyed that I didn’t write about it myself; Nazi content on this website isn’t hard to find, and I could have reported on it much earlier. That said, I am glad that a mainstream publication is addressing the issue.

It’s been known about for a long time, and Substack, to its enormous discredit, has done nothing about it. Instead, they’ve worked to explicitly elevate “alt-right” types like Richard Hanania, with this simpering puff piece and accompanying podcast by Substack cofounder Hamish McKenzie. When Huffington Post writer Christopher Mathias revealed Haniana’s past as an overt white supremacist writing under the pseudonym “Richard Hoste,” Substack’s silence was deafening. They did not retract or otherwise repudiate their article, or even really address the controversy. As the Atlantic article makes clear, Substack already has terms of use that ban “hate,” but they’re not enforcing them. Instead they’re striving to be edgy, sucking up to weirdo Silicon Valley accelerationists, and making cringeworthy ads:

Please note this isn’t about encouraging “free speech,” a position I have a lot of sympathy for, because Substack aren’t genuine free speech maximalists. If they were, they’d allow all non-criminal speech, including explicitly protected and legal forms of free speech like pornography and other kinds of sex work. They don’t, and this makes them free speech hypocrites.

With Substack’s Nazi problem now very much out in the open, the platform now has a choice: enforce their terms of use and evict the vile people who make a living (and make money for Substack) by peddling overt hate to huge audiences, or maintain their current course and become a Nazi bar. I suspect they’ll pick option B, which sucks. I have good friends who make their entire living from writing on Substack and the platform’s hypocritical, ideologically inconsistent free-speech-for-Nazis-but-not-for-boobies policy is putting writers in a terrible position. If they stay, it looks like they’re okay with being on a platform that doesn’t just permit but promotes hate. If they leave, they risk losing their livelihood.

Clearly, organised opposition is what’s needed. If this site’s writers banded together and threatened to leave Substack en masse, the resulting revenue hit might make continued Nazi-coddling untenable. Writers are already organising:

In my opinion, the choice is stark: if you’re a non-Nazi writer who objects to Substack making money from white supremacists (not to mention this site’s vast swathe of TERF writers and culture-war contrarians) you should make this extremely clear to the site founders, ideally in an organised, public way that doesn’t allow for individualised, targeted pushback. You could look to leave altogether, taking your subscribers and their revenue elsewhere: there are other subscription email providers that either have ideologically consistent free speech policies — allowing all legal speech, not carving out convenient exceptions for Nazis — or that don’t go out of their way to promote Nazis at all. Revolutionary stuff! Here are some alternatives:

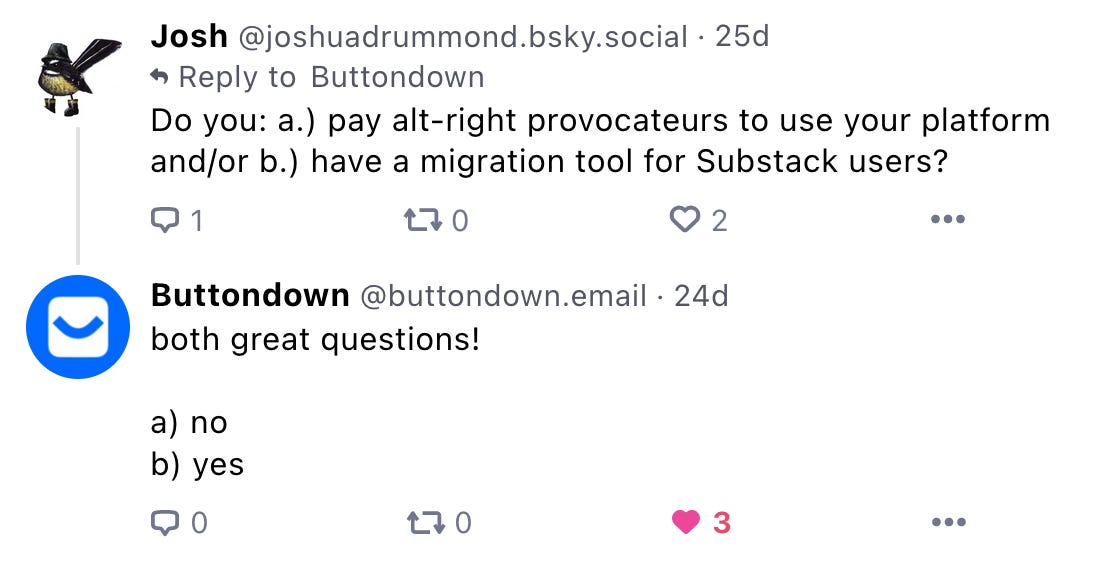

Buttondown

Buttondown is not “free” in the way Substack is (Substack takes a big cut of your subscriptions) but they’re an inexpensive option for independent publishers. Also they seem like good sorts on social, without any pretence of “creating a new economic engine for culture.”1

Here’s Buttondown’s Substack migration guide, including moving your paid subs.

Ghost

Ghost Pro is a very Substack-like experience for your newsletter and subscribers, with the option to self-host if you’re a tinkerer.

Here’s Ghost’s Substack migration guide, including moving your paid subs.

WordPress

WordPress.com’s Newsletter product now offers a paid email subscription option, including the ability to connect your existing Stripe account for paid subs.

There are other options out there too. For my part — as all my posts here and at The Cynic’s Guide To Self Improvement are free anyway — I will definitely be moving my newsletters to another platform if Substack doesn’t come up with a satisfactory response to their Nazi problem. It’s long overdue.

Yeet your phone

A few weeks back, I noticed my iPhone screen-time averages were starting get a bit silly. Like a lot of smartphone users, my device is set up to passively scold me for how long I use it, and last week it informed me that my use time was down slightly to an average of just… three hours a day.

This meant my average time the previous week was close to four hours a day.