Your cart is currently empty!

Category: The Cynic’s Guide to Self-Improvement

Substackers against Nazis

There’s a good chance you’ve seen the following letter a lot lately: I’ve been meaning to send it out for a while now. I’m sending it to recipients of both The Bad Newsletter and here on the Cynic’s Guide, because — to say shortly what I’ve said at length — having Nazis on your platform when you are not a free speech platform is bullshit. I could respect an absolutist free speech stance, but Substack is not a free speech platform. There are multiple forms of speech that are not accepted here, including sex work: try using Substack to send nudes or fire out some erotic fiction and see how long your account lasts. Still shorter version: Nazis yes, nudes no. And if you’re not going to be a true free speech platform, then I’m going to have to join the voices demanding that you get rid of the Nazis.

Of course, it goes further than Nazis, who are merely the tip of the Substack garbageberg: this place is a haven for hate and disinformation merchants of all kinds who are thrilled that Substack is giving them a platform and the ability to monetize. I’m putting a piece together on how Substack enables and encourages disinformation: look out for it soon at The Bad Newsletter.

Dear Chris, Hamish & Jairaj:

We’re asking a very simple question that has somehow been made complicated: Why are you platforming and monetizing Nazis?

According to a piece written by Substack publisher Jonathan M. Katz and published by The Atlantic on November 28, this platform has a Nazi problem:

“Some Substack newsletters by Nazis and white nationalists have thousands or tens of thousands of subscribers, making the platform a new and valuable tool for creating mailing lists for the far right. And many accept paid subscriptions through Substack, seemingly flouting terms of service that ban attempts to ‘publish content or fund initiatives that incite violence based on protected classes’…Substack, which takes a 10 percent cut of subscription revenue, makes money when readers pay for Nazi newsletters.”

As Patrick Casey, a leader of a now-defunct neo-Nazi group who is banned on nearly every other social platform except Substack, wrote on here in 2021: “I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling. The cause isn’t going anywhere.” Several Nazis and white supremacists including Richard Spencer not only have paid subscriptions turned on but have received Substack “Bestseller” badges, indicating that they are making at a minimum thousands of dollars a year.

From our perspective as Substack publishers, it is unfathomable that someone with a swastika avatar, who writes about “The Jewish question,” or who promotes Great Replacement Theory, could be given the tools to succeed on your platform. And yet you’ve been unable to adequately explain your position.

In the past you have defended your decision to platform bigotry by saying you “make decisions based on principles not PR” and “will stick to our hands-off approach to content moderation.” But there’s a difference between a hands-off approach and putting your thumb on the scale. We know you moderate some content, including spam sites and newsletters written by sex workers. Why do you choose to promote and allow the monetization of sites that traffic in white nationalism?

Your unwillingness to play by your own rules on this issue has already led to the announced departures of several prominent Substackers, including Rusty Foster and Helena Fitzgerald. They follow previous exoduses of writers, including Substack Pro recipient Grace Lavery and Jude Ellison S. Doyle, who left with similar concerns.

As journalist Casey Newton told his more than 166,000 Substack subscribers after Katz’s piece came out: “The correct number of newsletters using Nazi symbols that you host and profit from on your platform is zero.”

We, your publishers, want to hear from you on the official Substack newsletter. Is platforming Nazis part of your vision of success? Let us know—from there we can each decide if this is still where we want to be.

Signed,

Substackers Against Nazis

Shut Up To Succeed

There’s this skit at the opening of the Tenacious D song “Kielbasa” that starts with KG saying “Dude, we gotta fucken write something,” and because I got into the D at an impressionable age and the lyrics are burned into my hippocampus with letters of fire, I think of this song every damn time I’m behind on a deadline, which is most of the time. And yet I resisted writing this piece, for a few reasons.

One is that I’m spooked by success. A few years back, I did a tight five minutes at a comedy open mic. I’d done stand-up sets before, to varying results, including quite a lot of laughter and at least one obligatory crash and burn. This time I was determined to get it right and I did. I learned the material backwards, including a few alternative paths should a particular punchline flop, the crowd laughed their collective asses off and I left the stage on a high. “That was brilliant!” I thought. “I can’t wait to do that again,” and I never have.

The other reason I’ve been avoiding writing this particular piece is that I’m not sure that telling people about what I’m looking to achieve is a good idea. You may have heard, as many who’ve read self-help have, that you need to make your goals public, or tell people what you’re trying to achieve, for reasons of “accountability.” Many, including Tim Ferris, suggest publicly announcing your goal, or making a bet with a friend (if I don’t do X by Y, you get to keep $Z dollars.)1

The idea is that publicly announcing a goal will help hold you accountable. But, as is usual in the field of self-help, the advice is wildly conflicting. Many authors suggest telling no-one (or as few people as possible) about what your goal is or what you’re working on. According to numerous sources, some of them credible, telling people your goals can affect the likelihood of achieving them.

Naturally, I’ve just Googled the topic, and I’ve immediately hit someone taking the bit way too damn far, because that’s always how it goes in this ridiculous field. “Why telling your goals is a fatal mistake” screams one of the first Google hits. Fatal? Really? Unless the goal is “skydive without training” or “build an electric blanket from scratch” I doubt it’s going to be deadly, but let’s find out. The piece, which I nearly stopped reading in the second paragraph when it mentioned neuro-linguistic programming, is by a bloke called Peter Shallard. He describes himself as “a renowned business psychology expert and therapist gone renegade.” This last seems accurate: his “About” page contains no formal qualifications.

It suggests that if you tell people about what you’re up to, it can give you the same kind of mental reward as actually doing the thing you’re telling everyone about. Just because I’m cynical about Shallard’s qualifications doesn’t mean it’s all a load of rubbish, though. Other pieces by more credible authors — like Atomic Habits mega-seller James Clear — suggest the same effect.

If that’s right, it’s a bit cooked for me, because I have a newsletter that’s about all the different self-help shit that I do, and telling you about it may be dooming everything I try. Having an audience for my stuff hasn’t helped me achieve my big goal, which was to post regularly: if anything, it’s made it harder. Some people pay me actual money for this writing, others seem to like it enough to hang around for each epistle, and this frankly freaks me out a bit. I always worry that I’m disappointing you.

Fortunately, when you dig into the research it gets both vague and highly specific. Good science tends to come loaded with caveats, and the original paper that everyone references, by a bloke called Peter M Gollwitzer, is no exception. As you can read for yourself, the experiments in the study have a rather tangential connection to reality. They measured whether students would do stuff like “watch videotaped study sessions for slightly longer” or “compare yourself to variously-sized cartoons of lawyers and indicate which one you feel most similar to.”2

I’m not mocking this. It’s real science, the conclusions are both interesting and valuable, but they’re not necessarily broadly applicable to the real world. That never stops self-help writers from immediately making it so, though.

Where does that leave us? Is it a yeah or a nah on telling people about your goals? How about: why not both, or neither? I think the answer depends on what sort of person you are, or what kind of goal you have in mind. If you’re the sort of person who really needs others to give you a rev up, by all means tell a few specific people about what you’re trying to achieve. Or if you thrive on working on something in secret to surprise people later down the line, do that. Curiously, this approach gels with some of the research I mentioned above, which suggests that if your goal is founded in identity — “I wanna be a gym guy/gal/nonbinarino” — then telling people about it is likely to reduce the effectiveness of the goal. But if it’s founded in something more specific — “I wanna bench press 100 kilos” — then the identity condition might not apply, and perhaps it’ll be helpful to tell others or otherwise have people help you out.

All the above is my long-winded way of telling you that, somehow, I’ve managed to consistently go to the gym for a few months now.

Again, caveats. I am using the word “consistently” slightly outside of its conventional calibration. I’ve noted the date of each gym session since August, during which I managed to go a grand total of four times. In September I went three times, a 25 percent decline, but October picked up nicely with seven attendances. In November I went nine times, and so far in December I’ve managed to go every other day.

Improbably, I love it.

I can’t quite put my finger on what changed: the nearest thing I can compare it to is the same buzzy “I hate this, but I like it” feeling I get from taking cold showers — and I’ve been doing those for well over a year now. I’ve also refined my workout a bit: I followed a plan one of the gym trainers set me for a while, and now I’ve shifted to a strength-building workout that’s easy to understand, hard to master, and never stops getting harder.

The other reason I like the gym now is that it’s working. A while back I noticed that a bunch of my favourite t-shirts were getting too small. I’d definitely outgrown shirts before, usually around the tum region, but this was a bit different. They were pulling up at the shoulders and into my armpits. Never mind, they were going to holes anyway. I consigned them to the painting-rag box.

Then it started happening to younger shirts, and I couldn’t pretend that it was anything to do with the age of my shirts or our washing machine. I’ve got bigger, in a way I wanted and planned and worked to get bigger, and that is very satisfying. Much more importantly, the numbers on the Heavy Metal Things are going up, too. In August I was knocking around a 40 kilo bench press and drawing this not-smiley face next to it: 😐

Today, my best bench press is close to double my August numbers. The emoji has changed to this: 🤨

This isn’t the plan, but the meme is timeless so I made sure to include it. Back when I started this newsletter, I was using how many pull-ups I could(n’t) do as a success metric. I stopped updating progress because I was embarrassed the number wasn’t going up, which is what happens when you don’t, uh, work out. But I do now, and the numbers are in: I’m doing 20+ pull-ups in a given gym session — and that’s in between my other exercises. I’m pretty pleased with that. Pull-ups are hard. But it’s still early days. I have a specific and quite ambitious goal in mind for how much I’d like to be able to lift: the goal is to bench-press 100 kilos, and to be able to do a muscle-up, which is probably the most aptly-named callisthenic exercise in existence.

No-one except Louise and my t-shirts has noticed that I’m going to the gym, but I’d like to think that’s not why I’m going. I read once that, one day, you pick up your child for the last time, and — as an older dad — I want to delay that day for as long as possible. If I keep tracking the way I am now, I’ll still be able to yeet my boy Leo well into adulthood, and that’s exactly how I want it.

Hopefully telling you about it won’t stop it from happening.

I originally titled this newsletter “Harder, Better, Faster, Shorter” not just to get the Daft Punk song in your head but because it was meant to be shorter than normal. That hasn’t worked out, but oh well. Substack lets you do surveys, so I’ll pop this one here – I want to find out what kind of newsletter frequency you’re actually after here.

And, as usual, I look forward to chatting in the comments.

Yeet your phone

A few weeks back, I noticed my iPhone screen-time averages were starting get a bit silly. Like a lot of smartphone users, my device is set up to passively scold me for how long I use it, and last week it informed me that my use time was down slightly to an average of just… three hours a day.

This meant my average time the previous week was close to four hours a day.

“I had my reasons!” I reasoned. There are lots of apps I use for work — Gmail, Slack, others. I’d written a time-consuming and fraught article on Christian Zionism for Webworm and I’d spent a lot of time popping in on the Substack app to check on the comments. And there was, uh, Instagram. Gotta check the ‘gram, right? How else would I know what my rapidly ageing millenial cohort were up to?

But four hours seemed excessive.

At the risk of pointing out the obvious, there are only 24 hours in a day, and 8 of them (if you’re lucky) you spend asleep, so four hours is… a lot. There’s lots of other things I want to be doing, not least of which is consistently updating my self-improvement newsletter.

I started writing this article, and then I was taken with the sudden urge to Do The Maths.

It was very depressing, and it went like this:

Let’s assume I’ve spent three hours a day on a smartphone since I got my first one. It was more than 10 years ago, but we’ll be generous and allow for just one decade of smartphone use. What’s more, we’ll say that I only used it for three hours a day for six days a week. Inventing a kind of smartphone Sabbath should allow for any days I used it less than three hours.

So. There are 52 weeks in a year. Multiply 52 by 6 and that gives us 312: how many days I use my phone in a given year.

(Ironically, I am using my smartphone’s calculator app to do these calculations.)

Multiply 312 by the 3 hours a day I use my phone and I get 936. Nine hundred and thirty six hours a year.

Shit.

Let’s multiply those 936 hours by 10 years and that gives us… 9,360 hours over the last decade. God.

How many total days is that?

Break out the division. 9360 hours divided by the 24 hours in a day will give us the total number of days.

It’s 390.

Three hundred and ninety days.

Fifty-five weeks and four days.

About one year and one month.

It’s the equivalent of being on my phone continuously, day and night, without stopping, for more than a year.

What?!

I must have the maths wrong. I check it with my wife. She’s a primary school teacher, this kind of maths is her bread and butter.

(At this point I really did go upstairs and check the preceding paragraphs with Louise.)

Unfortunately, I am right.

It’s not just me. And it’s not just you. Estimates of average daily smartphone use vary, but reputable studies put it at between 2 hours a day (at the low end) and almost 6 hours a day (at the high end.)

What’s more, the only thing more popular than smartphones might be the desperate search to disconnect from the damn things. Scratch the surface and the articles are everywhere: “Device-addicted parents struggling to curb kid’s screen time,” worries an RNZ headline, with a buried lede that parents are struggling even more to curb their own screen time. Linked in the RNZ story is a piece by NYU professor John Haidt with the (contested) theory that “Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls.” Meanwhile, the Spinoff has a helpful power ranking of all the ways writer Madeleine Holden has tried to curb her own smartphone addiction, and advice columnist Hera Lindsey Bird has a …broad spectrum of suggestions:

There are easy things you can do to limit how interesting your phone is. Mute all but essential notifications. Make everything grayscale. Kill every potential source of dopamine. You could get an alarm clock, or even better, a clock radio. You could charge your phone in another room. You could swap your phone for a fax machine. You could swap that fax machine for a water blaster, and comprehensively clean all your walkways.

Take all these anecdotes of compulsive use, add users’ desperate desire to quit, and you’ve got something that looks a lot like an addiction. There are plenty of people who’ll tell you that this waddling, quacking bird is definitely a duck. If you’ve ever searched the topic you’ll be familiar with explanations like this one from Stanford professor Anna Lembke, who suggests our smartphones have turned us into “dopamine addicts.”

“We can very quickly then get into this vicious cycle, where we’re not reaching for something to feel good, but rather to feel normal or to stop feeling bad.”

Continuous over stimulation of the brain’s pleasure pathways worsens the situation, she says.

“If I continue to bombard my brain’s reward pathway with these highly reinforcing drugs and behaviours, I eventually end up with so many Gremlins on the pain side of my balance, that not only do I need more and more to get the same effect, but when I’m not using, I’m in a dopamine deficit state, I’ve got a balance tilted to the side of pain.

“I experience the universal symptoms of withdrawal from any addictive substance, anxiety, irritability, depression, insomnia, craving. And I will then seek out that drug not to feel pleasure, but just to stop feeling pain.”

It seems clear that smartphones can be addictive, but there’s always the danger — as so many self-taught self-improvement influencers do — of biffing babies out with the dopamine bathwater. Thanks (ironically) to my unhealthy YouTube habit, I’m exposed almost constantly to people who pick up the notion of “dopamine fasting” and run off a cliff with it. To make some points that should be obvious: Smartphone use is not a closed loop, there are an infinity of things that make people happy or sad that predate smartphones by a few hundred thousand years, and you need dopamine to live. The list of extremely legitimate reasons to use smartphones is long. In many countries, the villages that we need to live and work and raise children are all but gone, and in place of spaces where we walked and talked together are a billion lonely boxes, each containing social creatures with a desperate need to reach out. If you can’t do physical, then digital will do. If you’re a new mum, nap-trapped by an infant, sending memes to your mates might be what’s keeping you sane. And if you are an activist or a journalist or a politician or an artist or one of any number of things, a huge part of your job takes place in online social spaces, and you need to Post.

And for years, that’s what I’ve told myself: I’m an artist, and I write, and I need to be online. Reading an article or ten feels like virtous work, as does scrubbing through a tutorial on YouTube. What I watch is often deeply entwined with my identity. And it has to be said that screens are, in many ways, wonderful. During the pandemic, I could keep in touch with family and friends all over the world. My son knows his grandparents and cousins by sight; in ye olden 90s we would have made do with voice-only phone calls, photos and (if we were lucky) a videotape. Having all the world’s knowledge, a high-powered camera, and even a calculator (take that, maths teachers) with me at all times is a boon.

Yet. These days, as I scroll, it’s accompanied with the feeling that I’ve been conned. Looking at the numbers, it’s clear: I’ve spent more than a year of my life on smartphones and the return on investment is terrible. You could excuse the sheer amount of time spent if there’d been something to show for it — a big social media presence, the ability to code, learning a language on Duolingo, a consistent output of pretty much anything creative. But I can’t make any of those claims. I know life is about much more than “productivity,” but even with that caveat my phone time is staggeringly unproductive. I post perhaps twice on Bluesky or Mastodon on a big day. Instagram is maybe once a week. Nearly all the time I spend on my phone (and, if I am being honest, my computer) is in passive consumption. Lurking. I don’t have many good memories of the half of my life I’ve spent on screens, or in fact any strong memories at all; it’s all one amorphous, algorithmic blob of memes and blogs and socials and takes.

My first thought on doing all those calculations was: how am I even finding the time to use my phone this much? I’m busy. I have a demanding day job. I have a social life. I’m a dad to a toddler. I cook and clean and walk and go to the gym. There’s practically never a time when I am on my phone for more than 20 minutes at a stretch. I think I could count the times I’ve spent more than an hour in one session on one hand.

But a bit of thought solves the not-mystery.

It’s the in-between times. 5 minutes here. 15 minutes there. Opening the phone to a notification of a text from a friend only to open Insta to be reminded of a meme you want to send to another mate but only after watching a mildly interesting reel lifted from someone else’s Tik-Tok. It adds up quickly.

It is, to age myself with a simile, like changing gears in a manual car. If I’m finishing a task (let’s say, the weekend morning dishes) and I need to do something quite different (let’s say, go to the gym) a nice smooth gear shift will have me picking up heavy things in no time. But add my phone to the mix — a quick reply to a mate, an email check to see if that package has shipped yet (hope, nope), scrolling to pick the right playlist or podcast, pausing to download an audiobook — and it’s like leaving your car to idle in between gears, eventually to slow down or stop. Suddenly it’s 25 minutes later and getting a full workout in before I need to take my son to his appointment is impossible. May as well not go!

This sort of thing happens all the time.

It seems frighteningly obvious that the life I want to live is being eaten by my smartphone screen.

In fact, it’s so obvious that the only reason I can think of for not giving it due attention is because of how frightening it is.

I felt like a character in a whodunit who’d always known who dun it but was too scared to admit it.

And that’s just smartphones. Once you add TVs and computer screens to smartphone use, things get scary. Time spent on screens goes from a worryingly significant fraction of life to the overwhelming majority of it, to the point where the words “HE LOOKED AT SCREENS” would make a cruelly accurate epitaph.

My brain’s so cooked by it all the only way I can visualise it is in meme form:

Here’s the thing: for all the advice richocheting around the Internet on how to curb your Internet-adjacent addictions, there’s probably only one thing for it.

Cal Newport, the irritatingly fresh-faced author of a couple of self-help books I’m sure I’ll get around to reviewing one day, puts it succinctly. (You don’t have to watch the whole video. This clip should start it right at the relevant bit.)

Yes, that’s right. The answer was right there in the Book of Mormon1 all along.

Just… turn it off.

I took the medicine. Just before I started writing this article, I deleted all the social media apps from my phone. Twitter? X’d it. Mastodon? Mastadon’t. Bluesky? I blew it right off. Reddit? More like didn’t read it. Instagram? Instagone.

I wish I could say that I felt better instantly but it’s been several days now and I’ve felt twitchy and tired and I keep picking up my phone and putting it down for no reason at all.

If smartphone use is an addiction, this seems about right for withdrawal symptoms. I’ll say this: it does feel startlingly similar to when I quit smoking.

I don’t expect my productivity to suddenly peak. I’m an accomplished procrastinator; life will find a way.

But if I can get those lost slices of life back — those moments of necessary boredom, of smoother gear-shifts in between tasks, of seeing my son playing instead of gazing into the abyss of my phone and having it algorithmically gaze back — then it’ll be worth it.

I’ll let you know how I go. If you decide to do something similar, I’d love to hear how you manage.

EDIT: Annoyingly, I just found out I accidentally sent this newsletter out with comments for paid subs only, which is the Substack default, and wasn’t my intention. I’ve fixed it now, so comment away!

Also I got this notification this morning. It’s still too much, but it’s a big improvement. The system works!(?)

For entertainment purposes, if by “entertainment” you mean “being crushingly depressed,” I have made a spreadsheet you can use to calculate your own abyss-gazing tendency: how many years of your life it’s taken to date, and how many it will remove from your future. Just put your age in years in cell B1, how many years you’ve had your smartphone in cell B2, and your average daily hours of smartphone use in cell B3. Enjoy!

Yeet Your Phone: The Spreadsheet.

-

The stage musical, not the actual book. ↩

-

Heavy lifting

Every other day, I leave the box I live in, get into a box with wheels, and travel to another box, where the heavy things are.

Once there, I pick up the heavy things and put them down. I do this again and again.

It is as exciting as it sounds.

But if I don’t do this, I will not be as strong as I would like to be, and my back will hurt, and I will become grumpy and fretful, and I will not look the way I want to look.

Plodding amongst the heavy things, my mind wanders to what I have been reading.

I think Naomi Klein is the greatest intellectual of the 21st century, which sounds much too wanky. So let me put it another way: I think she is brave and clever, and she writes books I cannot stop thinking about, that perfectly articulate and go some way to explain and perhaps even fix the sheer state of — well, just look around you.

Her latest book is called Doppelganger. It is about doubles, the strange way that our society constructs fake problems that reflect very real ones, and lifts up people and organisations who champion the twisted, backwards values of this mirror world.

And there are many reflections on branding, on influencers, and on self-improvement.

She writes:

It has often struck me, as I have contemplated my own branding crisis at a time when I felt I should be more properly focused on the climate crisis, that I am hardly the only one who has turned away large fears in favor of more manageable obsessions. In fact, it makes a certain kind of sick sense that our era of peak personal branding has coincided so precisely with an unprecedented crisis point for our shared home. The vast, complex planetary crisis requires coordinated, collective effort on an international scale. That may be theoretically possible, but it sure is daunting. Far easier to master our self, the Brand Called You—to polish it, burnish it, get the angle and affect just right, wage war against all competitors and interlopers, project the worst onto them. Because unlike so much else upon which we might like to have some sort of impact, the canvas of the self is compact and near enough that it feels like we might actually pull off some measure of control. Even though, as I have discovered, this, too, is a grand illusion.

And so the question remains: What aren’t we building when we are building our brands?

And as I lift heavy weights on to a heavy bar to make it much heavier I think: what aren’t I building when I’m in this box building muscles?

They say “may you live in interesting times” is a curse, and it is, but I feel like “may you always feel like you should be doing something else,” carries almost as much, uh, weight.

This, combined with the gym’s tyrannical boredom, always has me on the cusp of not going.

But I carry a book with me, and in the book are numbers. They tell the weight of the heavy things, and the number of times I have picked them up and put them down again.

My job is to make the numbers go up.

This is very difficult, and the difficulty almost makes the boredom tolerable, while simultaneously creating a powerful desire to go home.

And yet, when the numbers do go up, there’s a good buzz in the brain. Progress! A tangible difference! Something that’s not getting so much fucking worse!

Klein writes:

In Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer, Barbara Ehrenreich, who died in September 2022, tracked the ways that the quest for health and wellness became obsessive pursuits in the Reagan and Thatcher era and has only grown in influence since. She argued that this turn was a reaction [to] the failures of revolutionary movements, when the high hopes of the 1960s and ’70s slammed into the brick wall of ’80s neoliberalism.

With dreams of justice dashed, along with collective visions for a good life, it was everyone for themselves—a world of atomized individuals climbing over one another to get an edge in newly deregulated, precarious job markets. It was in this context, she argued, that so many turned their attention toward perfecting the body, with treadmills replacing protest marches and free weights replacing free love. The pressures were far greater for women at the start, but soon enough even heterosexual cis men would face their own unattainable fitness and beauty standards and myths. For Ehrenreich, this was all “part of a larger withdrawal into individual concerns after the briefly thrilling communal uplift some had experienced in the 1960s … If you could not change the world or even chart your own career, you could still control your own body—what goes into it and how muscular energy is expended.”

File as “too real,” I think, when I read this. We are beset by crisis, are quite literally awash in it, and the response of most so-called leaders is — almost invariably — to blithely make things much worse. Apart from the kabuki performance of voting every three years, and increasingly tormented howling at the abyss of optics-obsessed political media, there isn’t much I feel like I can do. Attempting self-improvement in the face of climate change, disasters, and genocide often seems like folly, but the bigger folly might be to do nothing. At the gym, I can make the weights go up, and the numbers get bigger, and (should I make an alliance with my constant nemesis, consistency) strength will follow. And it seems to help with the back pain I get from all the sitting and writing I do.

Explaining her own longtime, often conflicted relationship with the gym, Ehrenreich wrote: “I may not be able to do much about grievous injustice in the world, at least not by myself or in very short order. but I can decide to increase the weight on the leg press machine by twenty pounds and achieve that within a few weeks.”

I have never been a gym rat, but I can relate… As the climate crisis accelerates, with the land heaving beneath us and burning around us, I expect that many of us will continue to find comfort in whatever small bodily obeyances we can muster. There is solace to be found there.

There is a solace to be found at the gym. And a silence, in the sense that I wear noise-cancelling headphones and listen to a lot of Rage Against The Machine. I tell myself it’s because the gym music sucks (it does) but really it’s so I can pretend to be alone.

I head towards a machine and prepare to rage at it. I don’t know what its name is. All I know is that’s where I do my genuflections, Cable Bicep Curl and Cable Tricep Push-down. There’s a bloke standing at the machine, also wearing headphones. I point. He raises his index finger. One set left. He finishes, I take over. Not a word between us.

Klein writes:

For the person dedicating themselves to transformation through diet and fitness, there is you as you are now, and—ever present—there is you as you imagine you could be, with enough self-denial and self-discipline, enough hunger and enough reps. A better, different you, always just out of reach. Ehrenreich wrote evocatively of the strange silence of gyms, a place where people gather together in close quarters but barely speak to one another except to negotiate access to machines. This, she observed, is because the primary relationship at play is not between separate people working out, but between the person working out and themselves as they wish to be, their body double.

Sometimes it seems, in a broken society to which There Is No Alternative, that even the autonomous zone of the self is increasingly illusory and compromised.

Occasionally at the gym, usually in between sets, I feel the guilt of having spare time and cash to spend on making myself bigger and stronger. This is privilege, of course. Self-improvement itself often seems like something only the privileged have the privilege to be interested in.

I tell myself there are some privileges no-one should have, and there are some privileges everyone should have.

Everyone should have enough.

Lots don’t, I think, as I buy myself vegan protein powder in a plastic packet.

Klein writes:

In many ways, the most successful influencers in the wellness and fitness worlds—the people who make fortunes from selling idealized versions of themselves and the idea that you, too, can attain nirvana through a project of perpetual self-improvement—are a perfect fit with far-right economic libertarians and anarcho-capitalists, who also fetishize the individual as the only relevant social actor. In neither worldview is there any mention of collective solutions or structural changes that would make a healthy life possible for all.

Eventually my streak of gym-every-other-day falls apart. I get a cold and spend a week crook. I write one of my howling into the void articles, and then there’s an election. If you’re a climate change enjoyer, the result is thrilling. Slightly disturbed by the number of people who (accurately) describe my writing as grim, I write a follow-up that’s intended to be the opposite of grim:

The Brighter FutureSaturday starts out sunny, so we catch the 9:05 rapid from Kirikiriroa to Paeroa. The plan: beach day. We make it to the station with time to spare, which isn’t too bad, as it was kind of a snap decision, and we’d only started biffing beach things into bags half an hour before getting on our e-bikes. The Bad News Letter

The Bad News LetterApparently that one makes people cry. Heads you win, tails I lose.

Over this time, my self-improvement newsletter languishes. It is hard to write about self-improvement when you feel like you’re not improving yourself. And it’s hard to go to the gym when you’d much prefer to go with mates but no-one can ever organise to do anything at the same time and the thought of talking to random gym-goers makes you want to puke.

Often, it feels like the only accessible community is in the increasingly fraught world of our smartphones.

I usually leave my phone in my bag when I’m at the gym, because if I look at it I get caught up in some aspect of our world’s perma-crisis, some humbug or stupidity or cruelty or ecocide or genocide, and the session takes twice as long. And I might be tempted to take a selfie, to feed Instagram with Content and build a Brand.

Our addiction to digital media, our desire to offer up bits of ourselves to a digital machine in return for enough clout to make a crust, is itself a kind of doubling, Klein writes:

At best, a digital doppelganger can deliver everything our culture trains us to want: fame, adulation, riches. But it’s a precarious kind of wish fulfilment, one that can be blown up with a single bad take or post.

The fear of the bad take. I get it. I have been wanting to write something about the horrors taking place in Palestine and Israel1 — vicious attacks perpetrated by cruel men that take the lives of thousands of innocent people — and find myself warned off by the fact that to express an incorrect opinion about this mass murder is to open yourself to vitriol, and yet to not post about it is seen as a betrayal, a refusal to bear witness. For — of course — we should not ignore what’s taking place: the murder of civilians, collective punishment, the destruction of homes and hospitals, the holding of hostages, the denial of aid, and near-constant dehumanisation, among a cornucopia of other crimes. But how much witness-bearing can you bear?

A glance at my feed will reveal videos of frightened children whose parents have been killed, and traumatised parents covered in the blood of their children, who were so desperate for some scrap of justice that they felt the only avenue left was to show the world their agony. It makes me weep.

It’s not done to shed tears at the gym.

I also think: This guy! He stopped going to the gym because he’s sad about Palestine? Waah!

My suffering is that I’m sad about their suffering, and their suffering is that their homes and families are being callously destroyed. It’s not comparable. I feel fury at what’s being done, and simultaneously feel bad for not feeling bad enough. And I think: sort it out, dickhead! It’s not about you!

But you can’t separate your self from the world, there’s no objective view to take, you can’t get out of your head, and all anyone ultimately has is some ability to choose how they react, and what to say.

I stay in my box, where no bombs are falling, where my child is safe, and — apart from the obligatory sharing on social media, and some impassioned conversations with friends and family — I say nothing.

Unlike me, Naomi Klein is brave and articulate. In a Guardian column, she offers the best opinion I’ve yet read on the horror in Palestine.

[A]ntisemitism (besides being hateful) is the rocket fuel of militant Zionism.

What could lessen its power, drain it of some of that fuel? True solidarity. Humanism that unites people across ethnic and religious lines. Fierce opposition to all forms of identity-based hatred, including antisemitism. An international left rooted in values that side with the child over the gun every single time, no matter whose gun and no matter whose child. A left that is unshakably morally consistent, and does not mistake that consistency with moral equivalency between occupier and occupied. Love.

After more than a week away from the House of Heavy Things I start to feel it. That spot in between my spine and left shoulder-blade starts its constant muttering and needling. Lifting weights in an airless box might have given me the latest in the long line of colds I’ve had this year; and yet, not going to the gym is making me sick. I need to get back to it, less because I want to grow new and interesting additions to my body, and more because feeling strong makes the load of life more bearable.

Naomi Klein writes of the tendency to avoid reality, of the urge to vanish into a mirror-world of fake news that’s somehow more bearable than the real news, and the way that inhabiting our own bodies can feel unbearable:

At bottom, it comes down to who and what we cannot bear to see—in our past, in our present, and in the future racing toward us…

We avoid because we do not want to be bodies like that. We do not want our bodies to participate in mass extinction. We do not want our bodies to be wrapped in garments made by other bodies that are degraded, abused, and worked to exhaustion. We do not want to ingest foods marred by memories of human and nonhuman suffering. We do not want the lands we live on to be stolen and haunted.

And she continues, showing how self-improvement itself can be a form of avoidance; instead of being drawn into a mirror world, one is drawn — like Narcissus — into a mere mirror.

Indeed, a central reason why so many of us cannot bear to look at the Shadow Lands is that we live in a culture that tells us to fix massive crises on our own, through self-improvement.

Support labor rights by ordering from a different store. End racism by battling your personal white fragility—or by representing your marginalized identity group in elite spaces. Transcend your ego with a meditation app.

Some of it will help — a bit. But the truth is that nothing of much consequence in the face of our rigged systems can be accomplished on our own—whether by our own small selves or even by our own identity groups. Change requires collaboration and coalition, even (especially) uncomfortable coalition. Mariame Kaba, a longtime prison abolitionist who has done as much as anyone to imagine what it would take to live in a world that does not equate safety with police and cages, puts the lesson succinctly, one passed on to her by her father: “Everything worthwhile is done with other people.”

I go back to the gym, on my own. Surprisingly, I manage to lift heavier heavy things and make the numbers bigger than all previous attempts.

It makes my back feel a bit better.

And in the muscle-trembling, delirious boredom of the mid-set break, I think — as I always do — of the ways in which, even when we feel alone, we can find other people to do something worthwhile with.

If you want a way to protest or to do something worthwhile about the human tragedy taking place in the Middle East, Emily Writes has resources and recommended actions to take:

What can I do to help stop this genocideKia ora friends. As requested, here is my best attempt at providing ways to help stop the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. I give my most sincere thanks to those who helped me with this guide, especially those Palestinian and Jewish folks who are grieving and afraid right now. Emily Writes Weekly

Emily Writes Weekly Feel free to feed back — as usual, comments are open and free — but know I’ll be keeping a very careful eye on them. The comments here are almost always thoughtful and kind but I do have to warn that Antisemitism or Islamophobia or excusing war crimes will not be welcome.

That said, feel free to talk about things in the comments that are not related to crises. If people want to chat about how many push-ups they can do now, I’m all ears.

-

I hate that I even have to do this, and I am extremely conscious of the fact that it’s absurd for a self-improvement newsletter to sound like a diplomatic speech, but if I don’t do this someone will lose it. I condemn Hamas for their war crimes and for their autocratic, anti-democratic rule of Gaza. I condemn Israel’s leadership for their war crimes, and also for turning Gaza into an open-air prison, and for their near-constant flouting of UN General Assembly resolutions and international law in general. I’m convinced that you should be able to say “war crimes are bad” without referring specifically to whose crimes, but apparently people think that the righteousness of their cause cancels out their war crimes. ↩

-

The #1 thing most adults wish they could get better at

Gidday Cynics,

This newsletter has been a long time coming. This is strange, because it’s one of the very few areas in self-improvement where I already understand the topic, I’m reasonably proficient at it, and I even know a bit about how to teach it. What’s more, it’s a popular subject. A couple of weeks ago, when I asked if people would like to know more about how to draw, people were keen. A bunch of you shared your stories in the comments:

I’d love to hear what you have to say about art in education ~ at school, all I ever wanted to do was succeed in art.

I was good at it, and didn’t give a fuck about any of my other subjects. When my results came back from my 7th form painting portfolio submission, I had failed, due to “too much pen and not enough paint”. It absolutely crushed me and I didn’t draw a thing for at least 4-5 years after that…

I WISH I could just make art. But my brain keeps getting in the way.

The above is, unfortunately, a common experience. Many kids have an instinctual love of art burned out of them by the school system, and this later haunts their adult efforts at visual creativity. Hopefully what I’ve got to say will show a way around it.

Love love loved this! Inspiring and relatable, esp as someone who has just started sketching, largely because words – for so long my main creative outlet – have begun to fail me.

Oof. I know that feeling. But it’s fantastic to have another outlet that isn’t writing, and in my experience, one can usefully inform the other.

I’d love to read more about your process and philosophy around art. I’m one of those who gave up as a kid because I was only good at reproduction but couldn’t draw anything realistic from memory, or creative that wasn’t based on a real thing.

Again, this is really common! In particular, being able to draw realistically from memory is bloody difficult — but it really is an acquirable skill.

I would love a bigger ‘art’ post. My daughter loves to draw but sometimes she will throw the pencil down & refuse to go any further because it’s not turning out the way she envisioned, and yet her wee drawings have so much joy and vitality in them and I don’t want her to lose that. It would be great to share some of your wisdom with her – she thinks your painting of Bianca is amazing too, so words from the actual artist will carry some weight (no pressure, haha!)

Once more: this is incredibly common. A huge number of kids go through a stage where they feel powerfully compelled to draw “realistically” but the shortfall between their ambitions and ability leaves them frustrated. Often, adults are of no help at all, because it’s easy for their attempts at support to backfire horribly. “Oh, honey, that looks wonderful!” is — in the mind of a child who’s trying to draw realistically — an obvious, patronising lie. It objectively does not look wonderful. And saying “Oh, don’t worry, it doesn’t have to look realistic! Just look at Picasso!” or something similarly well-meaning can be even worse, because you’re ignoring what they actually want to accomplish: to draw something that looks like what it looks like. And that leads us straight to the beginning of our lesson:

Nothing looks like what you think it looks like.

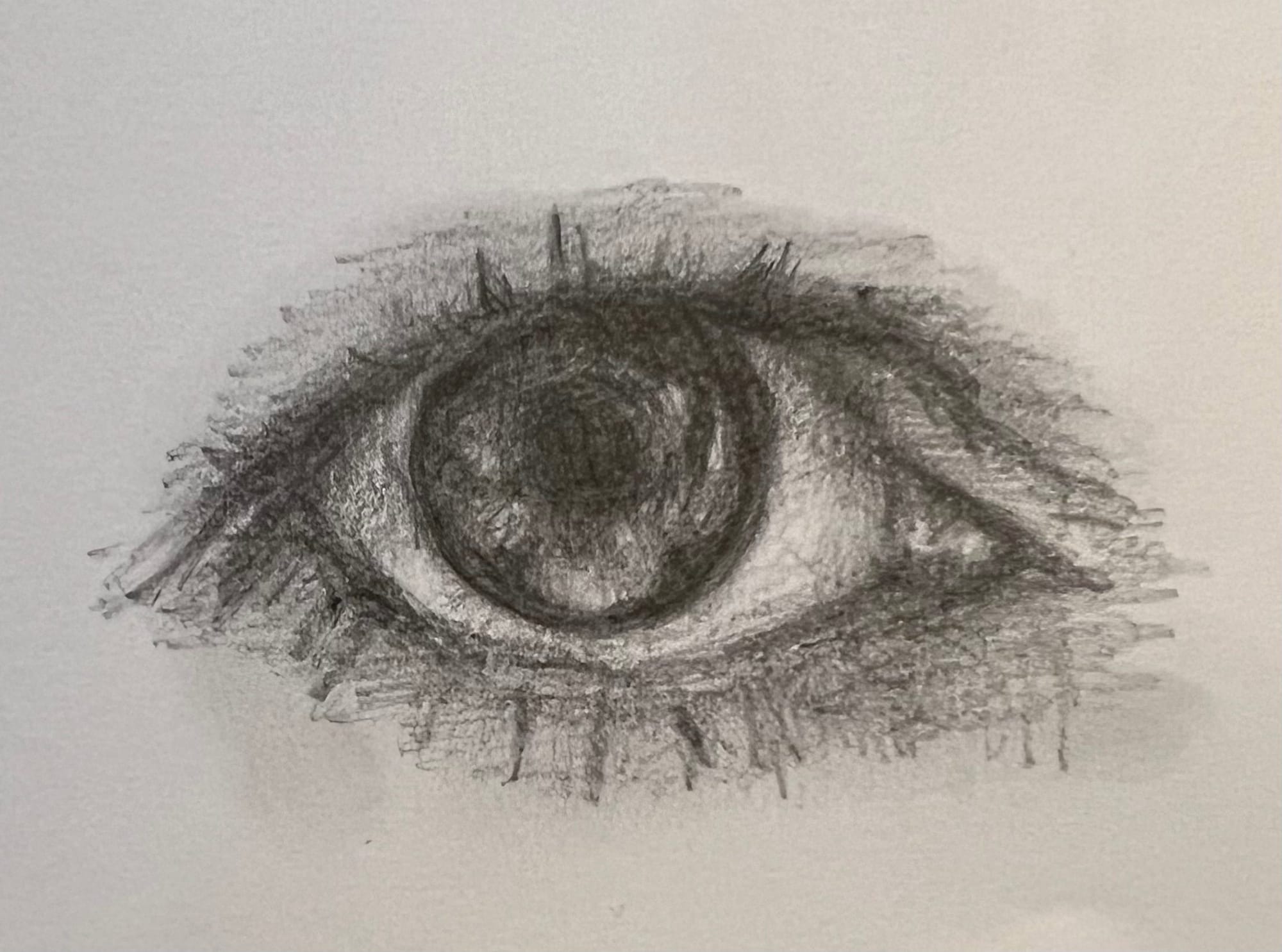

Look, I drew a thing. What do you see? It’s not a trick question: just react honestly, and then scroll down.

If you said a smiley face, well done! This is a fundamentally normal way to react to what I just drew. You might even have smiled back. As scientists at Australia’s Flinders University found, our reaction to a smiley face (or emoji, or emoticon) is a fascinating “integration of a learned and innate response.”

But with all that said, it’s just a circle, two dots, and a curved line. It’s not much like a face at all. To make the point, imagine what emoji would look like with realistic human features. In fact, to save you the trouble, I’ve found an example.

😂 Distressing, eh?

What about this one?

Eye see what you did there You can see where I’m going with this. A real eye is a ball of gristle and blood and goo, moist and gleaming, surrounded by folds of skin, hair, and greasy membranes. The window to the soul, perhaps, but only in the most Lovecraftian sense. Obviously, those curved lines and dots up there aren’t an eye, and the longer you look at it, the less like one it appears. It’s just a symbol. So why do we see it as an eye?

There are a number of answers to that question, and they go some way toward explaining why drawing is so hard for many people. But the easiest (if not strictly accurate way) to explain the answer is to flip the question on its head: it’s not just that we see a symbol as an eye; it’s that we see real eyes as symbols. And, as it turns out, pretty much everything else.

You call that an eye? THIS is an eye. There’s nothing wrong with this. We need symbols, least of all for reading. Children almost invariably draw symbolically. Adults who haven’t learned to draw “realistically” can still draw symbols; this is the reason that self-confessed terrible artists can absolutely slay at Pictionary while people like myself can be quite bad at it. And I need to be careful: I am using metaphors to plaster over several lifetime’s worth of art instruction, psychology, and neuroscience. Obviously, we do not literally see the world as hieroglyphics1, but there’s some weird shit going on that only becomes clear when you either dig deep into medical literature or try to draw something realistically, and the seeing-the-world-as-symbols metaphor will start to make sense.

Let’s talk seeing. As you’d expect, seeing begins with the eyes, but they’re only part of the picture. The rest is (neuroscience term incoming) brain stuff. Seeing is important to humans, and enormous brain resources are dedicated to it. Weirdly, images are processed in the back of the brain, with the optic nerve running all the way from the back of the eyes to near the rear of the brain. What’s more, the nerve flips half-way, to ensure that the images from your left eye are processed by the right side of the brain (which runs the left side of your body) and vice versa.2 Oh, and because of how lenses work your eyes receive images upside-down, like looking through binoculars backwards: it’s your brain’s job to flip them up the right way. Confused? Don’t blame me, blame either a. evolution, or b. the Creator’s ineffable grand design. It amounts to the same thing in the end.

This is just the start of it, though. Only the central part of your retinas are able to perceive colour well: but the fact that you appear to see everything in rich colour is a trick performed by your brain. Ever seen a cat out of the corner of your eye but it’s actually a rubbish bag? Brain stuff: your grey matter simulates what things might be before it concludes what a given thing actually is. Are you able to tell how far away objects are, or catch a moving ball? Brain stuff. And can you tell instantly that your attempt to draw a self-portrait or a motorbike or a school-curriculum-mandated scene of a “Spanish” helmet sitting on a New Zealand beach does not look like what it’s meant to look like but — infuriatingly — you have no idea why, or how to fix it?

Yup. Brain stuff.

It can sometimes be alarming to realise what you see is not exactly what is, but it’s true, and can be proven with optical illusions. Here is one I nicked from the University of Queensland:

You probably know that A and B are the same shade, because you’ve seen optical illusions before and this is that kind of article. But your visual brain, just like mine, refuses to believe it. A is obviously lighter than B. Most adults cannot draw

It bears repeating: if you cannot draw, you are not alone. In fact, you are part of a large majority. You see art all the time, and this may make you think that drawing is a common skill. It is not.

Science has had a good crack at trying to understand how the cognitive conditions I’ve outlined relate to drawing. A 1997 paper titled “Why Can’t Most People Draw What They See?” concluded that:

(a) motor coordination is a very minimal source of drawing inaccuracies, (b) the artist’s decision-making process is a relatively minor source of drawing inaccuracies, and (c) the artist’s misperception of his or her work is not a source of drawing inaccuracies. These results suggest that the artist’s misperception of the object is the major source of drawing errors.

In other words, there must be some brain malarkey going on in how humans perceive objects that specifically relates to drawing. It’s not a matter of being clumsy, either. The study found that non-artists who struggled to draw recognisable objects or faces could still trace a photograph just fine. Yet “misperception of objects” is also clearly an oversimplification, which the authors admitted; perception of objects is something that most humans are fundamentally good at.

Since then, research has continued. “The difficulty adults find in drawing objects or scenes from real life is puzzling, assuming that there are few gross individual differences in the phenomenology of visual scenes and in fine motor control in the neurologically healthy population,” begins “The genesis of errors in drawing,” a 2016 review of the scientific evidence on the topic in Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews. “However, the majority of adults are rarely able to put down a passable likeness of their visual experience onto paper.”

This is Science for “look, sure, brains are different, but by and large most people tend to process images in similar ways and most people can pick up a pencil. So why is nearly everyone so shit at drawing?”

Their paper reviews a huge swathe of the available literature to come to the conclusion: it’s complicated. Just ask our resident scientician, Dr Lee Reid:

“The biggest factor is that the visual system breaks down into different pathways that interact but progressively become less and less connected to each other — and at the end of one of those pathways is your hand,” the actual neuroscientist says. “That pathway has evolved to guide your hands — or your feet or your head or whatever — towards objects or away from objects, so you can catch a ball and things like that. That uses a very different set of skills to identifying what something is.”

These different pathways, Lee explains, lie at the heart of why people often find drawing so different: there’s a physical distance between them in the brain and they aren’t very connected to each other. Imagine two large motorways, both with different destinations, and the only way between them is a dirt track that’s prone to flooding. Brains are creatures of habit, and forming new neural connections is energy-intensive, especially in adults. So, when the brain does try to connect the two different tracks — as in, when a non-artist tries to draw something — it prefers to avoid the dirt track, sending you on a detour via the well-travelled roads of Symbol Country.

“The processing in the middle breaks everything down to symbols, which you already have in your head. So it’s less that people don’t perceive things, it’s just that symbols are coming into play,” Lee says. He suspects that the ability to draw simply isn’t as evolutionarily useful as the ability to, say, pick things up, throw and catch objects, and know what stuff is. “Probably, when you’re learning to draw, what you’re actually learning to do is to connect the ends of those pathways a lot better.”

So, informed by these papers and my discussions with Lee, here’s my crack at what’s going on in the brains of adult non-artists when they try to draw something.

When you try to draw, you are faced with not just your brain’s penchant for symbols. You face that instinct plus dozens of optical illusions and cognitive delusions — perhaps more. You are trying to form new neural connections over an unfamiliar path that your brain would rather not use, which is always difficult, especially in adults. In all probability, you also face an inner critic who is perfectly capable of seeing that what you’re drawing doesn’t look anything like real life and isn’t shy about telling you in the strongest possible terms. And you are expected to (or are expecting yourself to) instinctively deal with or bypass this cognitive onslaught in order to render something realistic.

Without training, or a rare quirk of neuroatypicality, it’s like trying to do calculus without ever having learned how to add 2 + 2.

So, if you’ve ever beaten yourself up for not knowing how to draw, you can stop. It’s a miracle anyone learns to draw at all.

But, also miraculously, it’s almost certain that you can still do it.

Of course, there’s a self-help book for that. Luckily, it’s a very good one.

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain is an instructional book by Betty Edwards, former professor emeritus of art at California State University. First published in 1979, the book’s fundamental thesis is that abilities we’re taught to prioritise — writing, arithmetic, spoken language — are mediated by the left side of the brain, and more “holistic” abilities like drawing live on the right side of the brain. These are often repressed, but can be unlocked. It’s a fascinating theory, and it’s wrong. As partially detailed above (and explored much more thoroughly in the four decades of neuroscience and psychology research since 1979) it’s much more complicated than just left brain vs right brain.

However, where the book fails as science, it succeeds as metaphor and pedagogy. There is a good reason that, when asked how to learn to draw, working illustrators will often respond “start with Edwards.” When I first read it, as a kid who was “good at drawing” but was perpetually frustrated with the process, it blew the doors off my artistic development. Here’s the tenet that did it:

Drawing from life is just tracing what you can see.

This sounds ridiculous so please indulge me to prove the point. If you’re a non-artist, have a go at this exercise. You’ll look a little silly so either find a private spot or be prepared for intelligent questions from curious colleagues. Stop whatever it is you’re doing and look around you. Hold your head still. Shut one eye. Use your finger (or a pencil or pen) to trace the outline of objects around you in the air. It doesn’t matter what the objects are: a mug, chair, bunch of bananas, vase of flowers, a curious two-year-old. The more complex, the better.

Could you follow the outline of an object with your finger? If so, congratulations, you can draw. Drawing is just doing the same thing — on paper.

I understand this might seem too simple, especially for adults who might have struggled to draw many times and whose petulant inner 12-year-old art critic is even now stomping off in a huff.3 But that’s really it. This one simple trick™️ (artists hate it!)4 can help blaze a new neural path through years or decades of adverse conditioning. Again: take what you can see, and trace it, on paper. That’s drawing.

The other vital thing that Edwards offers is a way to disconnect from your inner critic. You’ll need the critic later in your drawing journey, but at the very start it’s a nuisance that simply can’t comprehend why your drawing doesn’t look like what you want it to. The right drawing exercises can help you first quieten the critic and then offer it gainful employment as an ally, with a minimum of self-scolding or hissing “shut up” to yourself.

But here’s the funny thing: perhaps because I already liked drawing and did a fair bit of it, this advice and a few basic exercises was enough to take my drawing to another level. I never actually finished reading — or working through — the book.

So. Want to go through it together? If you’ve been wanting to learn how to draw, this might be a great opportunity. Let me know in the comments, or reply to this email.

In the meantime, here is a time-honoured, counter-intuitive, meditative, and often quite trippy exercise that appears in DOTRSOTB, which contemporary neuroscience5 suggests actually has a lot to do with how artists draw all the time, and which we will use to temporarily unhook drawing from your ability to self-criticise. It’s called:

Blind contour drawing.

YOU WILL NEED

-

A pencil

-

A blank sheet of paper

-

10 to 20 minutes or so of free time

-

Hands6

Here’s how to do it. Sit at a table or desk. Put a piece of paper down. Take your drawing hand — it doesn’t matter if you’re right or left dominant — so you’re holding a pencil poised near the middle of the paper. (If you like, you can tape the paper to the table, to make the next steps a bit easier, but it’s not required.) Now, turn away from the paper, so you can’t see it, but leave your hand where it is, ready to draw. Position your non-drawing hand so you can see it clearly.

Now draw the lines of your hand — without taking your pencil off the page or looking back at the paper. Do it very, very slowly, as if you are tracing every fine line and detail in your hand with the pencil tip. This will drive your inner critic nuts. If you’ve ever doubted you have one, this will dispel this notion. Tell your critic it can look at the drawing — later. If you’ve done mindfulness meditation, this may feel familiar. Note feelings or thoughts and just keep drawing. Draw all the lines in your hand. Look for finer details, then draw them. It may feel a bit weird. It may feel very weird. You may feel as if your hand is a fractal infinity, an endless spiral of detail down to the very atoms, a masterwork of extraordinary and strange proportions that you’ve never truly witnessed before. Or you may be slightly bored and feel a need to go to the toilet. Roll with whatever comes up. If you accidentally take your pencil off the page, put it back down and keep going.

Then, after at least ten minutes, look at the drawing.

If you’ve done it according to the instructions, it will look like nothing at all. Or perhaps a topographic map, or a river valley, or strange, indecipherable writing. As always, your mileage will vary.

This is what mine looks like 😏 This exercise achieves two aims: it helps you learn a vital drawing skill — tracing the contours of reality — and produces something so abstract that your inner critic should have absolutely no idea what to do with it. Instruct it. Appreciate what you’ve made. “Look,” you can say to yourself. “I created something weird and beautiful, for myself, and for its own sake.”

And that’s art.

Thanks for reading. This article, like all my stuff, is free. If you have found it helpful, please share it, and encourage your friends to subscribe.

See you in part two, where we’ll discuss why you (almost certainly) never learned to draw as a kid, even if you did art at school.

-

If you do see in hieroglyphics, seek medical attention. ↩

-

I am oversimplifying. There’s some overlap because you (probably) have two eyes, and what’s in front of you is left of one eye and right of the other. ↩

-

I mention 12-year-old critics for a reason: 12 is around the age that artistic development often stalls out in children that don’t get adequate drawing instruction. If you’re a non-artist and you’re in a psychoanalytical mood, try drawing something complex and difficult, like your own or someone else’s face. You’ll probably have a bad time, but don’t worry about that for the moment. Instead, try to analyse the internal criticism that crops up. What does it “sound” like? Does it have a voice? What does it remind you of? Of course, your mileage may vary, but mine sounds a lot like a snot-nosed kid saying “Oh my goshhhhh this drawing suuuucks” and I don’t think that’s a coincidence. ↩

-

They don’t. Artists generally love it when more people learn art. ↩

-

Article too long, so this goes in the footnotes: new evidence suggests, incredibly, that skilled artists spend much of their time drawing blind. They’re looking at the subject of their drawing a lot more than they do at the drawing itself, which suggests the brain has learned to simulate what the drawing hand is up to. Here are Chamberlain and Wagesman with their explanation, my emphasis added: Large parts of the time spent drawing are spent ‘blind drawing’ during which time the artist does not look at his drawing hand. In a functional neuroimaging study, Miall et al. (2009) found that the act of drawing blind remains consistent with visually guided action, despite lack of direct visual input. ↩

-

You don’t actually need hands. You just need something complex to draw and a way to hold a pencil. I’m not being snide; history is replete with extraordinary examples of disabled people who do not have full or (any use) of their hands learning to draw. As a kid, I did some watercolours with our neighbour. Her mother had been poisoned by thalidomide while pregnant, and she was born with deformities in her limbs. Despite this, she was an excellent painter. I’m very grateful to this lovely person, who was very generous with her time to a curious 10 year old. ↩

-

Interlude

A quick one, this week, because, well…

Our cat Bianca died a few days ago. It was sudden. We’d hoped to have a couple more weeks, but she became unable to eat, and keeping her longer wouldn’t have been right.

She arched and smooched and purred in the vet’s surgery, right until the end.

There is a lot I would love to write about our wonderful cat’s passing, about the startling sadness that the death of a pet can create, about how it tangles up with the loss of other loved ones, and even stirs the ashes of grief past to reveal long-smouldering coals.

How tired being sad makes you.

When I try, I choke. I can feel the words rattling around up there, even hear them, but between up there and this keyboard, this screen, there is a relay that isn’t working. Like a cat that meows at the door and then won’t come in, as she did, as all cats do.

So I’ll talk about a video game I liked instead.

That screenshot is from Gris, a 2018 game by the Spanish developer Studio Nomada, and it came from nowhere — I saw it by chance on GamePass, a service I subscribe to sporadically — to become one of my favourite games.

This is because it is less a game and more an interactive painting, a work of the most stunning animation, and a rich, emotive soundscape.

It is about grief.

Gris leverages the notion of the stages of grief, which — while being medically mythological and psychologically problematic1 — can still have a use as art. In this case, the metaphor is literal: grief as actual video games stages. Hah.

It begins, as grief does, with the world shattering around you, plunging you into something unknown.

And you are battered and buffeted by storms that seem to come from nothing, from nowhere, and relent as quickly as they arrived.

And as you move through it, you find a way to live with grief; to appreciate its presence as a reminder of something you loved.

The gameplay mechanics, in one aspect, are simple but pin-point perfect platforming. On another, they are experiencing emotion. It’s not like merely looking or listening, it is performing it, living it.

Because of this, you can feel extraordinary catharsis as you move through the stages. It is precisely the same sort of release you get from putting on sad music when you’re feeling down, but multiplied (in my case, at least) ten thousand fold; it is homeopathy for the soul. With the notable and useful caveat that, for once, this homeopathy actually has an effect.

Gris is available on pretty much any device you might like to play games on, from PC to PS5. It’s even on the iPhone. I’d recommend it to anyone who likes meaningful art, music, or who has experienced loss, and I think that’s… pretty much everyone.

Your results may vary. With the stuff that’s happened over the last few months I could probably be brought to tears by an emotively-shaped paperclip, so take all this with a grain of salt. I think you’ll like the game, though. It’s only a few hours long. Give it a go, even (or especially) if you’re not normally a gamer. For my part, I’m just grateful to Gris for helping give form to something that’s so amorphous, so difficult to talk about. If there are any other games — or works of art, or movies, or albums — that make you feel the same way, then please feel free to talk about them in the comments.

And now, some housekeeping.

Season One is almost over.

I like the idea of splitting this newsletter up into seasons, like a TV show, or, you know, the year. And once I’ve got that last commissioned painting finished, I’ll have caught up on the things I was most behind on. Having actually achieved some self-improvement feels worthy of a demarcation. I am thinking of calling Season One The Baggage, because I feel like there’s a lot that I’ve unloaded from the brain’s endless conveyor belt, but I’m open to suggestions.2

Over the next season, I’ll be looking a lot at exercise science and associated myths, while I torture myself at the gym. I’ll be doing more picking apart self-improvement tomes in an attempt to find useful titbits. I’m still convinced that most self-help books are vastly inflated pamphlets, so I’ve decided to cut them down to a more appropriate size. For everything I find that seems broadly applicable and that actually works, I’ll be writing it up into a mini-book, that I’ll make available for free. Suitable (or unsuitable) title suggestions are very welcome.

And thanks to the enthusiastic feedback last time, I’ll also be putting together a couple of posts, or possibly more, during the season break about learning to do art, and how — if you’re not an artist yet — you can very probably get better at drawing than you ever thought possible. And if that sounds like a self-help book blurb, good! It’s true, though.

Bianca.

-

As this article explains, the “stages of grief” were actually created to give voice to lived experiences of people suffering from terminal illness. They weren’t conceptualized to be about the loss of loved ones at all. ↩

-

Season Two will probably be called Swole, or Mad Gainz, or something else enjoyably ridic. ↩

-

A NU START

When you’ve been painting for a stretch of time, something odd can happen.

Lift your attention from the canvas, and the world appears as if made of paint, impossibly bright and detailed. Nip out to get some groceries at night and the streets are a dappled mix of brushstrokes and tones; a light fan brush-stroke here, a dark dry-brush scratch just so. Clouds, trees, grass, houses, the sky; for a time, until the effect fades, you are living in a landscape by Matisse or Van Gogh or Bob Ross. It’s not too far off this scene in the Vincent Ward film What Dreams May Come.

In my experience, it’s worth taking up painting just to experience it.

This mild hallucination, which frequently persists into dreams, is called the Tetris Effect, although as my painting experience shows it can appear in more forms than just video games. I’ve been experiencing it a lot lately, because I’ve been painting up a storm.

Which brings me to our cat.

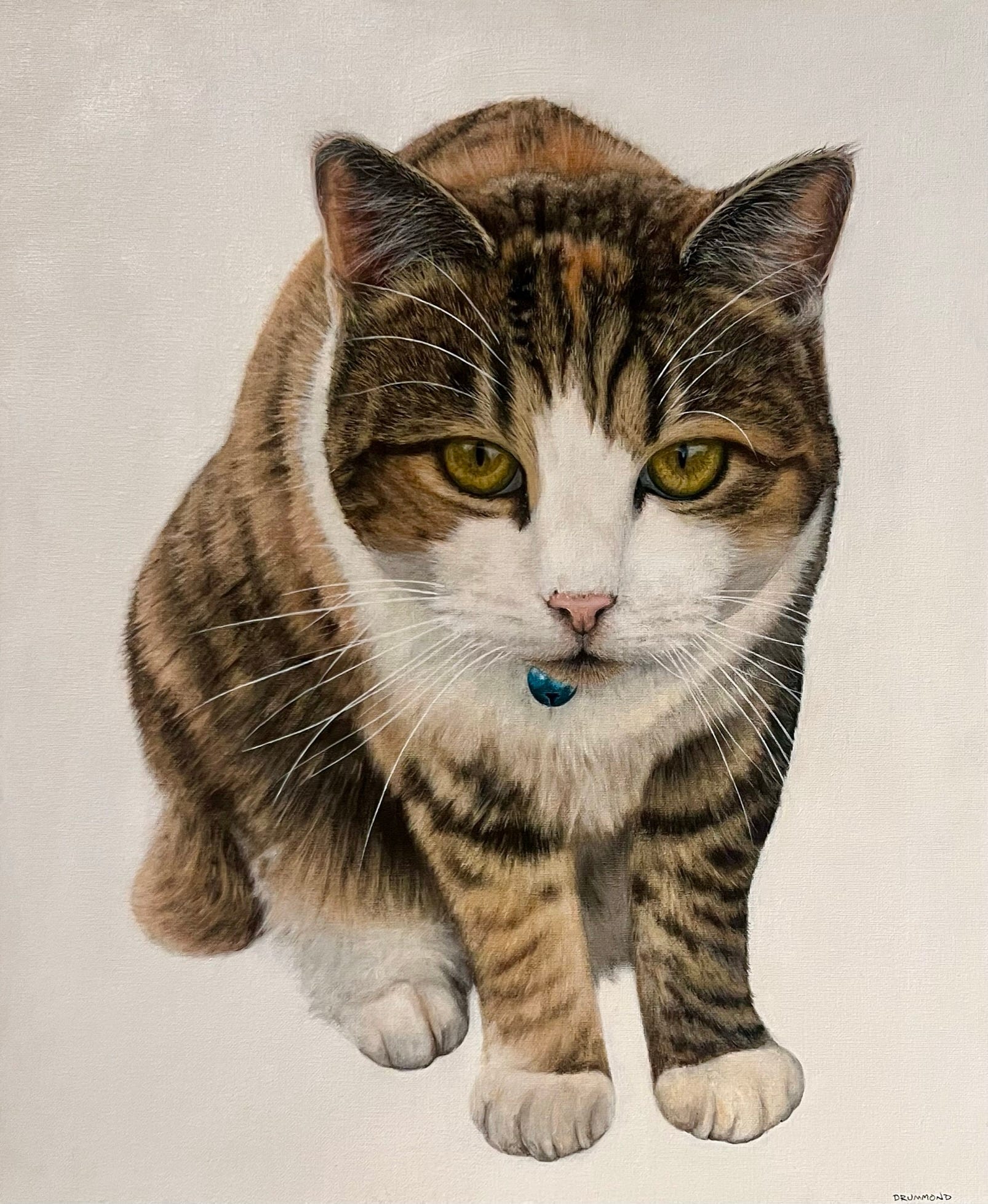

My then-girlfriend (now wife) and I fostered Bianca for the SPCA, and in the process saved her from a cat flu epidemic that swept the shelter. After that we couldn’t give her up. She’s been with us for almost 15 years. This long ago:

This is me and Bianca, before my head hair and facial hair swapped positions. This is her last month.

Bianca has had arthritis for a while now, and a mini-stroke several years back, but she’s stayed strong and happy throughout. A week ago we noticed she was looking straggly. This was odd, as she’d always been so clean, her pure white front looking freshly-laundered.

A half-hour trip to the vet. Cancer, inoperable. Euthanasia, this month, or sooner.

I wept the entire drive home.

Which brings me back to painting.

Some time back, a photographer friend took a stunning picture of Bianca, and when Louise saw it she fell in love. Instead of getting a print made, I offered to do a painting for her birthday.

Unfortunately, I missed the deadline by… quite a margin. I just checked and it turns out I optimistically posted “Anustart on anupainting” on Instagram in September of 2018, so it’s been almost five years. God. I thought it was three. In that time we’ve moved house several times and had a child. There’s been an election, a global pandemic, and much more besides. They managed to get rid of Donald Trump and turn Dune into a watchable film while I languished on a pet portrait.

A year later — having missed Louise’s birthday by a month — it looked like this.

All paintings go through an ugly stage, but this was something else. The proportions were all wrong. I put the painting aside for what turned out to be several years and returned to it after moving house, and began the process of repainting it from scratch.

The painting, the photo, and the subject. I worked on it on-and-off (mostly off) for a couple more years. The problem was the ambition: photorealism. It turns out that painting every individual hair on a cat that’s twice life size is both hard and time-consuming, and I kept banging my head against an unyielding skill ceiling.

I kept at it until Bianca herself gave me a sign. One day I went in to my studio to find that she’d made her own little addition to the painting.2

This is exactly what you think it is. She’d had some difficulty dislodging a clingy turd after a visit to the litter box and the little tart had chosen my painting of her as the perfect place to scrape her anus. I thought about chucking the painting out, but I’d sunk too much progress into it. So I scrubbed the shit off, taking a bit of paint in the process, and carried on, sporadically.

And after quitting everything else, and Nana passing away, then finding out Bianca’s diagnosis, I decided I’d had enough of sporadic progress. Our beautiful cat, witness to our marriage and birth of our child, who adopted neighbours and passers-by and road-workers and made a friend of everyone she ever met, who invariably came to us whenever we were sick or sad, who chirped and snuggled and purred.

Bianca might be dying, but before she did, I would make her immortal.

And, as of today, it’s done.3

It’s bittersweet, but I am still very proud of this piece.

Which brings me to self-improvement, because for many people learning to draw is one of the things they’d most like to self-improve at.

When I show my artwork, even (or especially) if it’s something I’m not particularly proud of, someone always says something along the lines of “oh, you’re so talented!” and it makes me wince. I don’t really think talent exists, or at least not in the way that people tend to use the term. They see the end product; I remember hours or days or in this case years of work and a cascade of mistakes and frustration, yelling “oh come on” and my favourite, “for fuck’s sake!” at the canvas. Someone once told me that it must be very soothing, doing art, and I laughed in their face. They were trying to be kind, and I wasn’t trying to be mean, but… no. Involving, yes, but it’s also a full spectrum of emotion that frequently includes mental and physical pain.4

And yet. There’s something there, or we wouldn’t do it. Once the necessary skill has been acquired you really can get into a flow-state doing art, and I’ve experienced it a few times — most recently while working on a commissioned piece that I decided, on a whim, to do in an abstract style. It was cathartic. I loved it.

Even on the more frustrating pieces is an enormous satisfaction in identifying where a piece needs work, and doing it; and with some artworks there is a moment that very much approaches magic; when you’ve all but finished the piece and the toil is more a memory, and you begin to see it as someone else might and the thought comes:

How the hell did I do that?

Which reminds me of another thing people say when they see finished artwork, looking crestfallen, wistful, sometimes even a little unconsciously angry: “I could never do that.”

This is a bubble I am happy to burst. Actually, you probably could! The ability to draw or paint things that look like what they look like is an acquirable mental trick. Practically all people with decent fine motor control and the ability to see can learn to draw to a standard they’d never have thought possible.5 There are many reasons they don’t, including time — it takes about six weeks, working for an hour or two a day, to get to a place of significant improvement when you’re starting from scratch — and their own history when it comes to drawing. Children often place a lot of importance on the ability to draw “realistically” and they can be hypersensitive to criticism right at the age that their cognitive and motor skills are advanced enough to actually do it. One careless “wow, that drawing sucks” can torpedo what might otherwise be lifelong love of making art.

There’s that, and the fact that the way art is taught in schools is terrible.

If people are keen — please let me know in the comments — I’ll do a longer post on art as a form of self-improvement, what’s wrong with art education, and how people can go about it in a way that works. For now, this is a status update. A big reason I started this newsletter was (somewhat paradoxically) so I could get more art done. Almost unbelievably, it’s working. Quitting everything to concentrate on just one (or, rather, several) projects has turned out to be the best self-improvement thing I’ve ever done. I’ve got more painting done in the past month than I have in previous years. But wait, there’s more. The yard is in at last in something approaching good shape, my job is going well, and I’m even managing to go to the gym.

Is this what self-care looks like? I’m not sure I know, not having a lot of prior experience.

I will miss Bianca, so much. But I’m glad to be able to use my skills to have a piece of her in our home forever.

Figuratively, and literally. I’m pretty sure some of the brown on that painting is hers.

Thank you for reading The Cynic’s Guide To Self-Improvement. It’s free, but you can pay me by sharing it around.

-

We were re-watching Arrested Development at the time. ↩

-

And the carpet, and my desk, and my keyboard. ↩

-

Apart from a coat of varnish. And there’s something about that left eye that’s bothering me NO STOP JUST STOP IT’S FINISHED GOD JUST LEAVE IT ALONE ↩

-

Every cartoonist (and writer) I know has a profoundly munted back and wrist from the constant sitting and seething. ↩

-