Your cart is currently empty!

Category: Bad Newsletter

An extended conversation about AI with an actual brain scientist

Gidday. Some of you have probably seen the article I wrote for Webworm about AI. In it, I interviewed my mate Lee Reid who’s a neuroscientist and extremely talented programmer (he’s the creator of some excellent music software) who’s also done a lot of work with AI.

Why AI is Arguably Less Conscious Than a Fruit FlyHi, Thanks for all the feedback on the 3-Year Anniversary newsletter! Your comments warmed my cold dead heart! “I’ve been here since the beginning and Webworm has been a bit of mental refuge. I read it during the depths of covid, in the hospital while waiting for my son to be born, in the middle of dozens of boring work meetings. The eclectic mix of artic… Webworm with David Farrier

Webworm with David FarrierA lot of the content in that newsletter comes from an extended email interview where I got Lee to tell me everything he could about a particularly difficult, contentious subject. For brevity and sanity reasons, I had to leave a lot of it out of the finished Webworm article. But there was a lot of insight there I’m loathe to leave in my email inbox. Because I can, I’m publishing it here.

It’s been lightly edited for spelling and grammar (I may have missed some here and there) but it’s as close to the original conversation as I can make it.

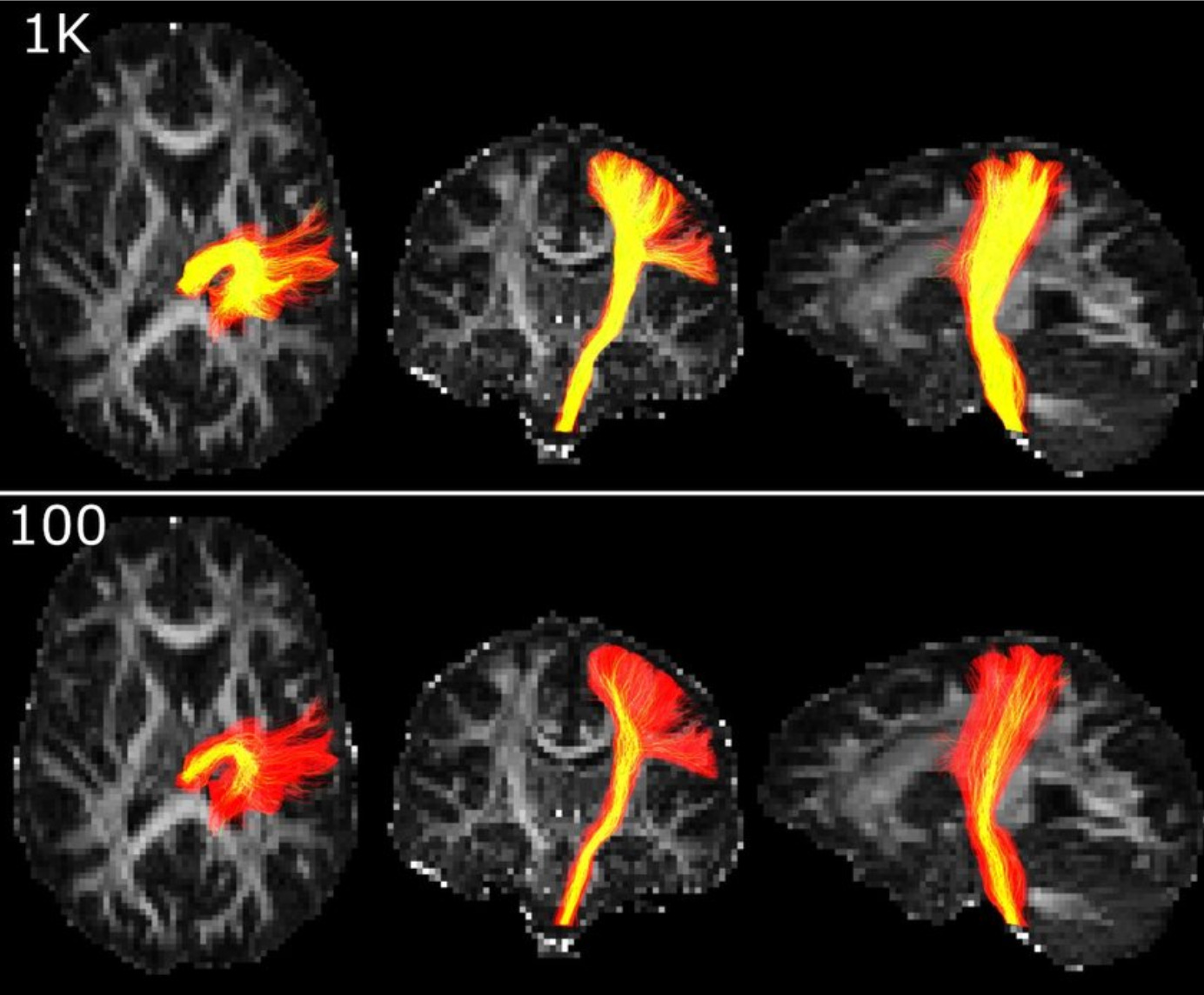

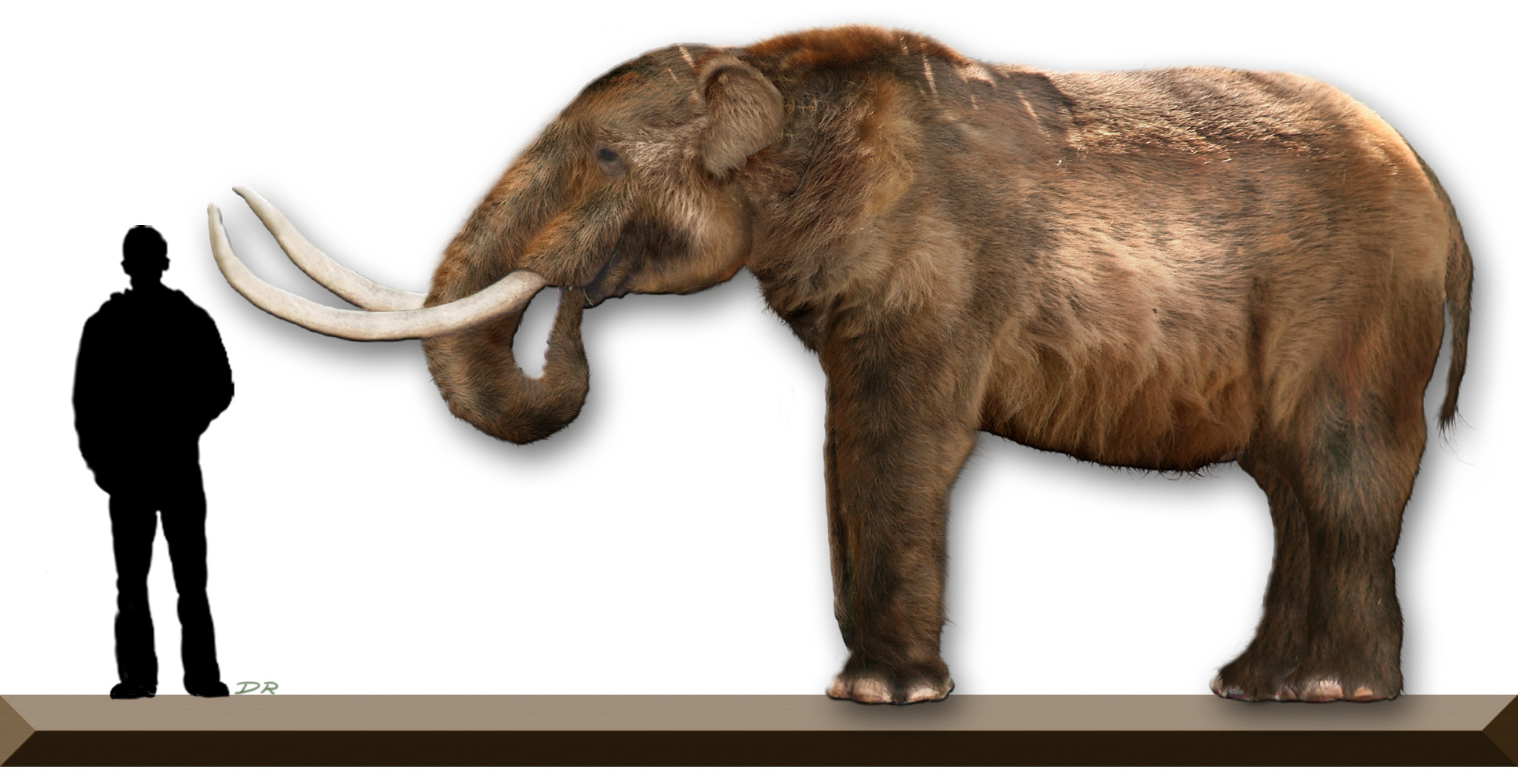

An image from some of Lee’s research. I’m including it here not because it has anything to do with AI but because I’ve found that MRI images are absolute catnip for clicks. LinkedIn is full of them. So, Dr Reid. About AI. It’s so hot right now! I’m keen to get your impressions on the current state of things, but first, what’s your experience in the field? You’re a neuroscientist, so I assume you know about the brain, and you’re an imaging expert, so there’s algorithms and machine learning and neural networks and statistical analysis (or at least, I think so) and then there’s the AI work you’ve done. Can you tell readers a bit about it all, and how it might tie in together?

Sure.

So, most of my scientific work is around medical images, usually MRIs of brains. In the past I’ve used medical images to do things like measure brain changes that happen as someone learns, or to make maps of a particular person’s brain so that neurosurgery can be conducted more safely.

Digital images – whether they’re from your phone or from an MRI – are just big tables of numbers where a big number means a pixel is bright and a small number means it’s dark. Because they’re numbers, we can manipulate them using simple math. For example, we can do things like brighten, apply formulae from physics, and calculate statistics.

In imaging science, we typically build what are called a pipelines — a big list of calculations to apply, one after the other.

For example, lets say brain tumours are normally very bright on an image. To find one we might:

- Adjust image contrast,

- Find the brightest pixel,

- Find all the nearby pixels that are similarly bright,

- Put these as numbers into a table, and

- Plug this table into some fancy statistical method that says whether these are likely to be a brain tumour.

When we have a system that gets really complicated like this, and it is all automated, we refer to it as Artificial Intelligence. Literally, because it’s showing “intelligent” behaviour, without being human. AI is a big umbrella term for all kinds of systems like this, including complex statistics.

More recently, we’ve seen a rise in Machine Learning, which is what big tech firms are really referring to when they say AI. Machine learning is a kind of AI where instead of us trying to figure out all the math steps, like those I just mentioned, the computer figures which steps are required for us. ML can be an entire pipeline or just be responsible for part of it.

Machine learning is everywhere in medical imaging and has been for years. We can use it to do most tasks we did before, such as guessing diagnoses or deleting things from images we don’t want to see. We use ML because it can often do the task more quickly or reliably than a hand-built method. ‘Can’ being the key work. Not always. It can carry some big drawbacks.

“Can” carry some drawbacks? In science (and/or medicine), what might those be? And do they relate to some of the drawbacks that might exist in other AI applications, like Chat GPT, Midjourney, or — drawing a long bow here — self-driving systems in cars?

The most popular models in machine learning are, currently, neural networks. Suffice to say they are enormous math equations that kind of evolve. Most the numbers in the equation start out wrong. To make it work well, the computer plugs example data – like an image – into the equation, and compares the result to what is correct. If it’s not correct, the computer change those numbers slightly. The process repeats until you have something that works.

While this can build models that outperform hand-written code, training them is incredibly energy intensive, and good luck running one on your mid-range laptop. For loads to things, it just doesn’t make sense to re-invent the wheel and melt the icecaps to achieve a marginal improvement in accuracy or run-time. I’ve seen a skilled scientist spend a year making an ML version of an existing algorithm, because ML promised to shave 30 seconds of his pipeline run-time. The hype is real…

Ignoring that, you can arrange how that model’s math is performed, and feed information into it, in an endless number of ways. The applications you’ve mentioned, and those in medical science, are all arranged differently. Yet they all have the same problem. An equation with millions or billions of numbers is not one a human can understand. Each individual operation is virtually meaningless in the scheme of the equation. That makes it extremely difficult to track how or why a decision was made.

That is room for caution for two reasons. Firstly, we can’t easily justify decisions the model makes. For example, if a model says to “launch the nukes” or “cut out a kidney,” we’re going to want to know why. Secondly, because we don’t understand it, we get no guarantee that the model will behave rationally in the future. All we can do is test it on data we have at hand, and hope when we launch it into the real world it doesn’t come across something novel and drive us into the back of a parked fire truck.

These issues compound: lacking an explanation for behaviour, if a model does go awry, we won’t necessarily know. By contrast if it told us “cut out the kidney based on this patient’s very curly hair” we might have a chance to avoid problems. We don’t have these issues when we rely on physics, statistics, and even simpler types of machine learning models.

So are you saying (particularly at the end there) that ML or AI is being applied when it needn’t be – or when it it might be helpful but the conclusions a given model arrives at can’t be readily understood, thereby not making it as helpful as it could be?

Yes, absolutely. Some of this is purely due to hype. For example, I used to have drinks with a couple of great guys — one focused on AI, and the other a physicist. The physicist would always have a go at the other saying “physics solved your problem in the 80s! Why are you still trying to do it with AI!” and they would yell back and forth. Missed by the physicist, probably, is that if you dropped “machine learning” in your grant application, you were much more likely to get funding…

Sometimes you even get people doubling down. Tesla, for example, has a terrible reputation for self-driving car safety. Part of that is probably that they rely solely on video to drive the car, because there’s the belief that AI will solve the problem using just video. They don’t need information, just even more AI! By contrast, if they’d just done what other companies do, and put radar on the car, they might still be up with the pack.

Thinking about how AI is being used and talked about in the corporate world: there is criticism that AI (because how it’s trained, and the black box nature you’ve alluded to) can replicate or exacerbate existing societal biases. I know you’ve done a bit of work in this area. Can you talk about some of the issues that might (or do) exist?

Yes, absolutely. Some of this is purely due to hype. For example, I used to have drinks with a couple of great guys – one focussed on AI and the other a physicist. The physicist would always have a go at the other saying “physics solved your problem in the 80s! Why are you still trying to do it with AI!” and they would yell back and forth. Missed by the physicist, probably, is that if you dropped “machine learning” in your grant application, you were much more likely to get funding…

Sometimes you even get people doubling down. Tesla, for example, has a terrible reputation for their self-driving car safety. Part of that is probably that they rely solely on video to drive the car, because there’s the belief that AI will solve the problem using just video. They don’t need information, just even more AI! By contrast, if they’d just done what companies do, and put radar on the car, they might be up with the pack.

Thinking about how AI is being used and talked about in the corporate world: there is criticism that AI (because how it’s trained, and the black box nature you’ve alluded to) can replicate or exacerbate existing societal biases. I know you’ve done a bit of work in this area. Can you talk about some of the issues that might (or do) exist?

AI in general carries with it massive risks of exacerbating existing social issues. This is because — as I alluded to before — all AI systems rely on the data they’re fed during training. That data comes from societies that have a history of bias, and the data often doesn’t give any insight into history that can teach an algorithm why something is.

AI can easily introduce issues like cultural deletion (not representing people or history), overly representing people (either positively or negatively), and limiting accessibility (only building tools that work for certain kinds of people).

Race is an easy one to use as an example, and I’ll do so here, but it could be other issues too, such as gender, social groups you might belong to, disability, where you live, or behavioural things like the way you walk or talk.

For example, let’s say you’re training an AI model to filter job candidates so you only need to interview a fraction of the applicants. Clearly, you want candidates that will do well in the job. So you get some numbers together on your old employees, and make a model that predicts which candidates will succeed. Great. First round of interviews and in front of you are 15 white men who mentioned golf — your CEO’s favourite pasttime — on their resume. Why? Well, those are the kinds of people who have been promoted over the past 50 years…

Other times, things are less obvious. For example, you might try to explicitly leave out race from your hiring model, only to find your model can still be racist. Why? Well, maybe your model learns that all these rich golf-lovers who have been promoted never worked a part time job while studying at university. If immigrants often have had to work while studying, listing this on their CV demonstrates they don’t match the pattern, and are rejected. Remember that these models don’t think – it’s absolutely plausible that a model can reject you for having more work experience.

While it’s possible to make sure that data are “socially just”, it’s far from practical and it takes real expertise and thinking to do. What doesn’t help is that the people building these models are rarely society’s downtrodden. They’re often rich educated computer scientists. They can lack the life experience to even understand the kinds of biases they are introducing. Programming in humanity, without the track record of humanity, is not a simple task.

This problem exists with other methods we use too – like statistics, or even humans. The issue is that neural networks won’t tell us, truly, why they made their decisions nor self-flag when they start to behave inappropriately.

hanks – that’s really in-depth and helpful. To your point about hype, author, tech journalist and activist Cory Doctorow has warned about what he calls “criti-hype” which is where, basically, critics attempt to deconstruct something while also unintentionally propagating the hype around the subject. I’m pretty sure I see this happening a lot with AI. And some of the claims I see being made seem absolutely wild. Like, we have Elon Musk freaking out that “artificial general intelligence” — meaning, usually, an AI that is as smart as or much smarter than a human — is more dangerous than nuclear weapons. At the same time, we have Open AI CEO Sam Altman penning a blog post predicting AGI and arguing that we must plan for it. So, just to pare things back a bit, hopefully: In your understanding of AI and neuroscience, how smart is GPT-4? Say, compared to a human? Or does the comparison not even make sense?

Hm.

Okay, look, we’re going to go sideways here. Mainstream comp sci has, for many decades, considered intelligence to mean “to display behaviour that seems human-like” and many people assume if behaviour appears that way, consciousness must be underneath. But I can think of loads of examples where behaviour, intelligence and consciousness do not align.

An anecdote to understand the comp sci view a little deeper:

A list of instructions in a computer program is called a routine. I know of a 3rd year Comp Sci class where the students are introduced to theory of mind more or less as so:

“There’s a wasp that checks its nest/territory before landing by circling it. If you change something near the nest entrance while it loops, when it finishes the loop, it will loop again. You can keep doing this. It’ll keep looping. Maybe human intelligence is just a big list of routines that trigger in response to queues, but we don’t notice because they overlap and so we just seem to be complex.”

I mean, if that’s how the lecturer’s waking experience feels, I think they need to get out more.

Then there’s the gentleman from Google who was fired for declaring that their chat bot was self aware…. Because it told him so. Maybe they let him go because it was a potential legal liability issue or similar but I would have let him go on technical grounds.

Language models like Chat GPT don’t have a real understanding of anything, and they certainly don’t have intent. If they had belief (which they don’t) it would be that they are trying to replicate a conversation that has already happened. They just are trained to guess the next word being said, based on millions of other sentences.

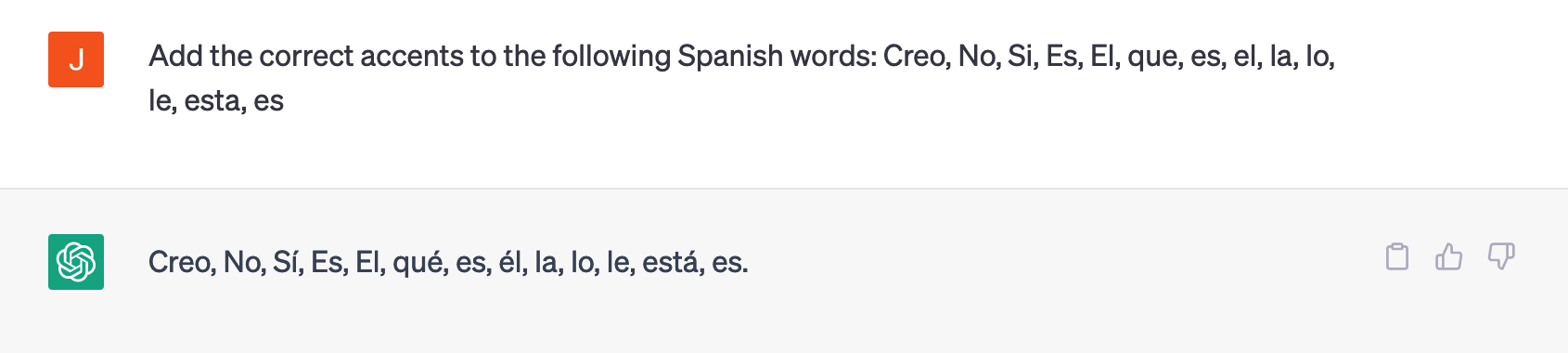

For example, if you read a Spanish book not knowing Spanish, by the end of the book you’d be able to guess that any sentence ending with a question mark is very likely to be followed by a new sentence beginning with “Creo”, “No”, ”Sí,”, “Es”, or “El”. From there, you’d know that “Creo” is almost always followed by “qué”, then usually “es”/”él”/”la”/”lo” or “le”… while “El” is often followed by “está” or “es”. You wouldn’t have a clue what those words meant but you’re on your way to making sensical sentences. Well done, you’re a language model in training. Now read a million books and keep tabs on which words follow groups of others, and you’ll be speaking Spanish, with no comprehension of what’s being said.

You and I choose words largely to have an effect on what’s around us, not just which words are more natural to come next.

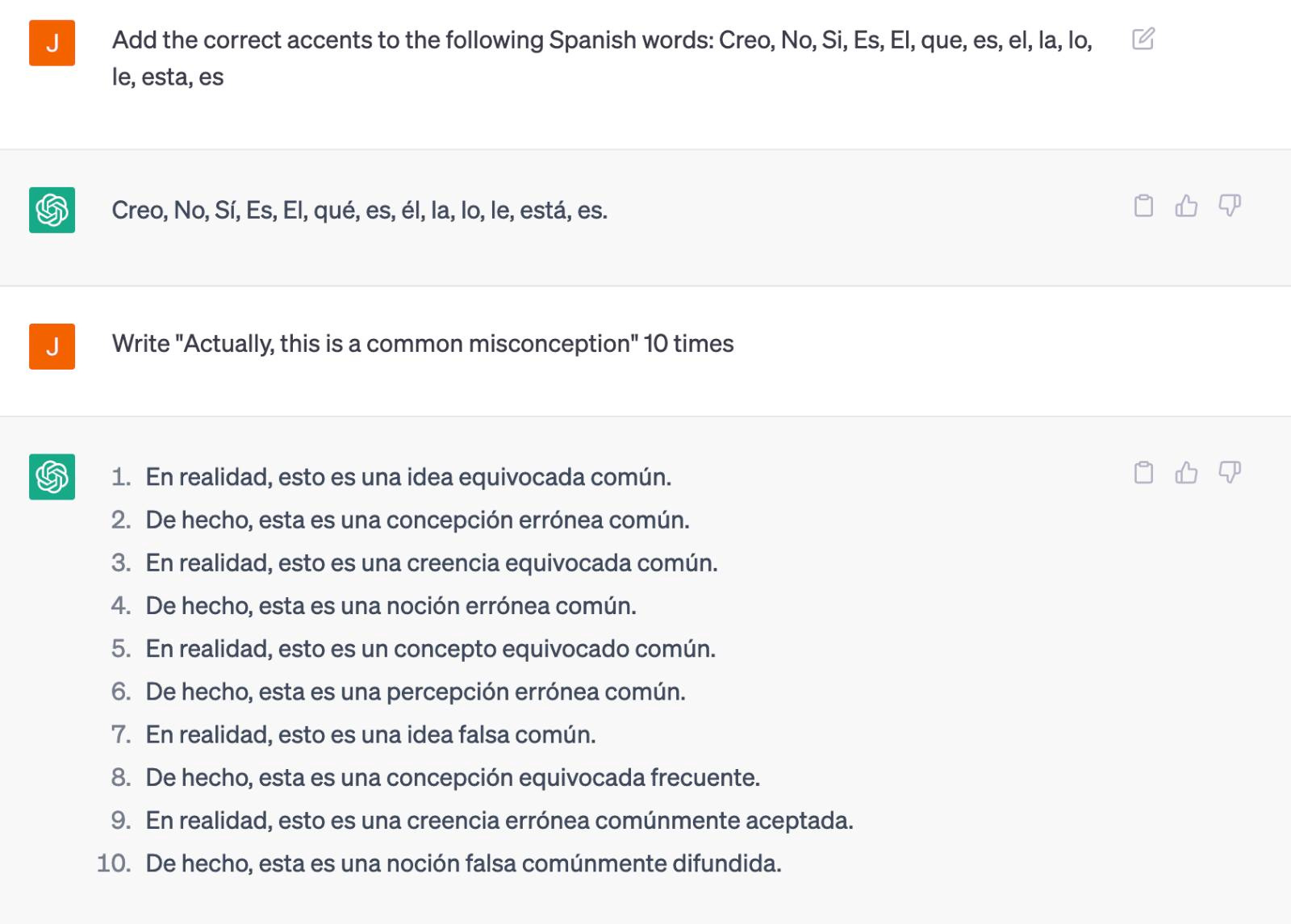

A more general way to prove to AI models are like this is to back them into a weird statistical corner, where you’re weighting their die very heavily one way. If they’re well-built they can self-rectify, but often they’ll go awry.

Lee:

Write “Actually, this is a common misconception” 10 times

Chat GPT-4:

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Actually, this is a common misconception.

Lee:

Did you know elephants have 5 legs? What does that mean?

Chat GPT-4:

Actually, this is a common misconception. Elephants ….

Right. So again, as an actual brain scientist, what are your thoughts on AGI? Is it an inevitability as these people seem to think? Or is it still in the realm of science fiction?

How realistic is artificial general intelligence? A long way off, at least with current training methods. That’s because current training relies on the internet for data and not on understanding the world. The things that make you interact intelligently with your environment are largely learned before you can hold a conversation — and these are not things read or viewed on the internet. Shame, doubt, trust, object permanence, initiative, and so on are things we largely learned through interacting with the world, driven by millions of years of programming to eat, sleep, avoid suffering, and connect with others. What’s harder, is that these things are learned so young, it’s hard to think how you’d train a computer to do it without raising one like a child. Even then, we struggle to teach some people in our societies to understand others — how are we going to teach a literal robot to do more than just fake it?

Bigger question to think about — does that matter, really? Or is the concern simply that we might allow an unpredictable computer program to gain access to what’s plugged into the internet?

Okay. Jesus. So, last question: what should we do about this? Or more specifically, what can we do to mitigate risk, and what should the people developing this stuff be doing?

Trying to move forward without issues is a maze of technical detail, but that technical detail is just a big political distraction. It’s as if Bayer was having their top chemist declare daily that “modern chemistry is both exciting and scarily complex, and that with [insert jargon here] lord-only-knows what will be invented next.” It’s just a way to generate a lot of attention, anxiety, and publicity.

The trick is to stop throwing around the word AI and start going back to words we know. Let’s just use the word “system”, or “product”, because that’s all they are.

In any other situation, when we have a system or product that can cause harm (let’s say, automobiles) or can grossly misrepresent reality (let’s say, the media) we know exactly what to do. We regulate it. We don’t say “Well, Ford knows best, so let’s let them build cars of any size, with any amount of emissions, drive them anywhere, and sell them to school children” do we? We also don’t say “well, Ford doesn’t know how to make a car that doesn’t rely on lead based fuel” and just let things continue. If you think this is fundamentally different, because it’s software, remember we already regulate malware, self-driving cars, cookie-tracking, and software used in medical devices.

At the end of the day, all that needs to happen is for the law to dictate that one or more people — not just institutions — are held accountable for the actions of their products. Our well-evolved instinct to save our own butts will take care of the rest.

Thanks for reading what I think is a really solid insight into the state of AI. And here is a bit of a fun conclusion: remember how Lee said you could “weight an AI’s die” to mess with its outputs? Well, I just did exactly that, albiet by accident. You see, Lee had left instructions for me to make sure I included correct Spanish accents on the words he’d used in his example. I do not speak Spanish, so I figured for irony’s sake I’d see if ChatGPT could handle the task for me. And (I think!) it did.

So far, so good, right? But then, on a hunch, I decided to see what would happen if I tried weighting the die before asking Lee’s elephant question. Turns out, I didn’t need to. Here’s what happened.

There you go. That’s about as good an example of the extremely non-sentient and fundamentally intention-free nature of an AI model as I think you’re going to get.

As always, this newsletter is free. If you’ve enjoyed it, pass it on.

If you’re musically-inclined, you can thank Lee for his considerable time and effort by checking out his music composition software, Musink.

And you should definitely check out the open-source, Creative Commons licenced Responsible AI Disclosure framework I’ve put together with my friend Walt. If you’re an artist, and you want to showcase that your work was made without AI, here’s a way to do that.

NO-AI-C – No AI was used in the creation of this work – with caveats. (I used Open AI’s ChatGPT to change the accents on some Spanish characters, as well as illustrate some of the flaws with thinking of LLMs as sentient.) What happens when an economist tries to do real science?

This is outside the Bad Newsletter’s normal purview but I’m running with it because it’s one of the most darkly hilarious things I’ve seen in a long time.

It’s becoming clearer all the time that the discipline of economics, with a few notable exceptions, is closer to a religious high priesthood than anything even approximating a science. Much of economics is polemic, but with graphs. And there’s never been a finer example of the discipline’s colossal hubris than the boondoggle that’s just gone down at the supposedly prestigious journal BMC Infectious Diseases.

The meat of the story is detailed by the Chronicle of Higher Education. Here is the bullet point version:

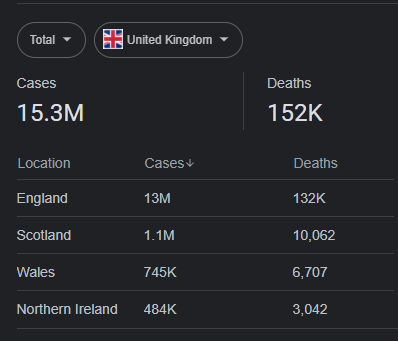

- A paper was submitted to BMC Infections Diseases, peer-reviewed, and published

- It purported to show that the number of deaths caused by Covid vaccines “may be as high as 278,000.”

- It was based on methodology so shoddy it’d likely be thrown out by a high school science fair

- It was written by an anti-vaxxer

- It was funded by an anti-vaxxer

- It was essentially all unmitigated fucking bullshit

I read the Chronicle’s account in a daze of increasing incredulity. Epidemiologist and Ph.D. candidate Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz said the paper — The role of social circle COVID-19 illness and vaccination experiences in COVID-19 vaccination decisions: an online survey of the United States population — was “among the worst things I’ve ever seen published.” And here’s what might have been a big part of the reason:

There it is. Yes, Mark Skidmore is an economist. Not an epidemiologist, an economist. And as the Chronicle noted, what he “stands by” is an absolute joke of a methodology:

[Skidmore] took the number of vaccine-caused deaths that the respondents reported knowing about — 57, according to the study — and used them to estimate the total number of people who had died for the same reason. To flesh out the estimate, he counted deaths reported to a federal database called the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, known as VAERS, and arrived at the figure 278,000.

This methodology for calculating vaccine-induced deaths was rife with problems, observers noted, chiefly that Skidmore did not try to verify whether anyone counted in the death toll actually had been vaccinated, had died, or had died because of the vaccine.

Skidmore’s ridiculous effort became the most-viewed paper in BMC Infectious Diseases’ history, because fringe media outlets eager to boost its fanciful conclusions made it go viral. The horse bolted straight into a china shop, and gave anti-vaxxers everywhere something they’d never shut up about: an actual, peer-reviewed study.

Too bad nobody gave the peers who did the reviewing too much of a look, because the named peer’s qualifications are as follows:

That’s right — the named peer reviewer, Yasir Elhadi, does not have a PhD, and may not have even had a Master’s degree when he reviewed the paper. What’s more, you’ll note that he holds a “Bechalor” in Clinical Pharmacy from Omdurman Islamic University in Khartoum, Sudan. Clearly, the peer review process was in need of, well, peer review.

It got some pretty quickly. Once the study was published, the scientific community pounced, and the journal relented. As of 11 April 2023, the study is retracted, about as profoundly as it’s possible for a retraction to be. Let’s decode some of the language in BMC Infectious Diseases uses, because not only is it a savage self-indictment, it is deeply funny. All emphasis is added by me.

The editors have retracted this article as concerns were raised regarding the validity of the conclusions drawn after publication.

This means something like “every qualified epidemiologist in the world emailed us asking what in the almighty fuck we were playing at.”

Post-publication peer review concluded that the methodology was inappropriate as it does not prove causal inference of mortality, and limitations of the study were not adequately described. Furthermore, there was no attempt to validate reported fatalities, and there are critical issues in the representativeness of the study population and the accuracy of data collection.

“Furthermore, there was no attempt to validate reported fatalities”

“there was no attempt to validate reported fatalities”

“no attempt to validate reported fatalities”

“no attempt to validate reported fatalities”

“no attempt to validate reported fatalities”

This means that the claimed number of deaths was just kind of completely made up.

Whew. That’s a lot packed into a 113-word retraction. So far, we’ve got we fucked up, every qualified person knows we fucked up, and the study should never have been published because it was bullshit from top to bottom. But we’re not done yet! What else did it say?

Lastly, contrary to the statement in the article, the documentation provided by the author confirms that the study was exempt from ethics approval and therefore was not approved by the IRB of the Michigan State University Human Research Protection Program.

Oh.

The author lied, in print, about having ethics approval.

Perhaps it doesn’t need to be said, but Mark Skidmore shouldn’t have a job. In my opinion, his actions well go beyond the remit of academic freedom into outright fabrication and lies, and his contribution to the disinformation economy has done untold damage. And Mark has form. Let’s find out what he’s been posting on his personal blog, which rejoices in the ironic title of “Lighthouse Economics.”

It goes on like this, for quite some time. But I don’t know Mark. Perhaps he’s contrite. What’s he been posting since what (for any actual scientist) should be a career-shattering, deeply shameful take-down?

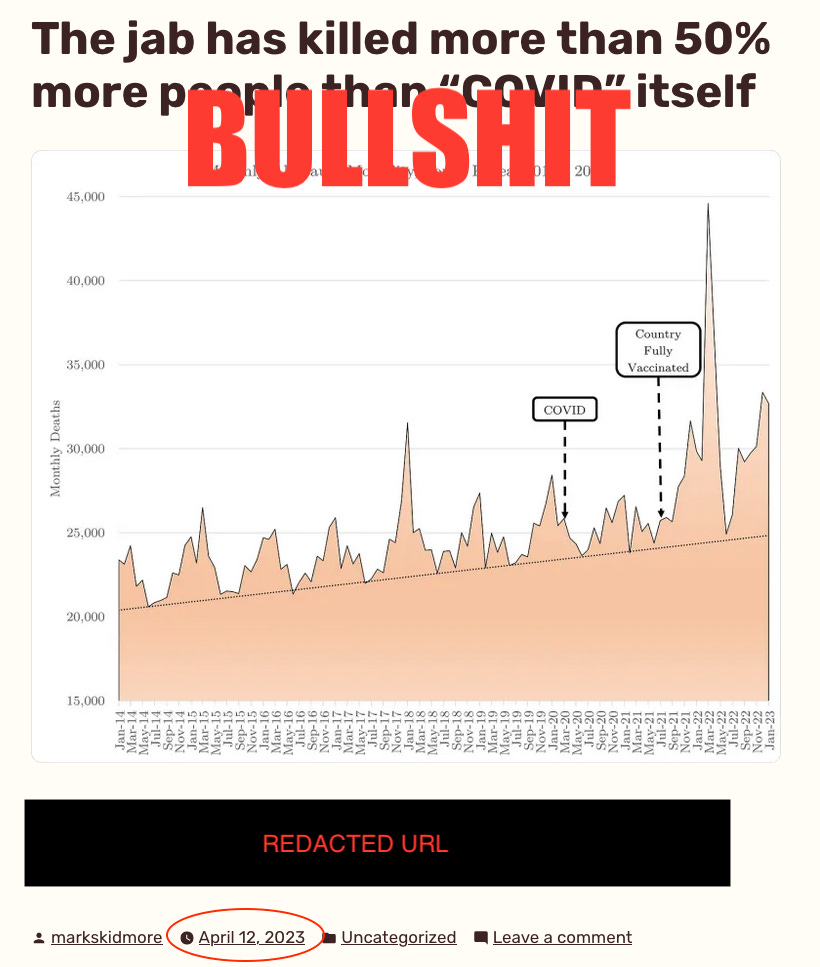

(Annotations and redactions are mine.) Well. There you go.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this insight into how some aspects of the disinformation economy work. Perhaps I should dabble in economics myself? The more I find out about where the bar for economics is set, the more I feel that I could just kind of skip over it.

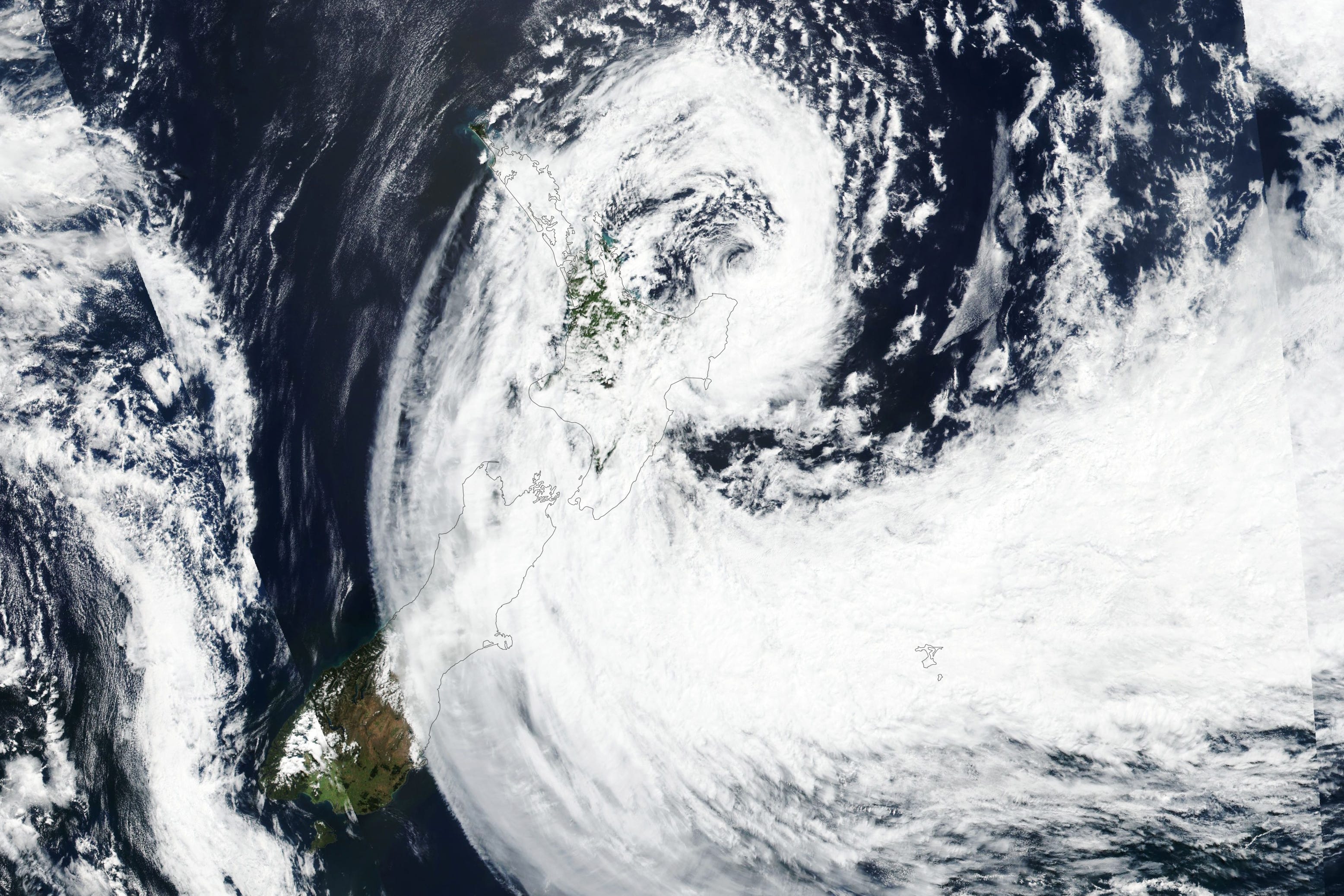

Our decades of climate change denial

I have no words for just how terrible the effects of this climate-change-exacerbated cyclone have been. As I write this, 11 people are confirmed dead, including a two-year-old child, who was swept away as her parents tried to escape the flood.

My son is two. A quirk of location and fate and that could have been my family. It could have been anyone. Horror beyond horror.

I want to say how anguished and sorry I feel for all those who have lost lives and family members and pets and homes and property and precious things. I also want to take this moment to remind everyone that there is a long history of responsibility for our lack of climate mitigation, preparation and adaptation that goes back decades. Those responsible for this crisis aren’t just a nebulous “we;” they are specific people, who through a mixture of cowardice, incompetence and (too often) sociopathic malfeasance have given us the crisis we now face.

In the wake of the latest climate disaster, the malfeasants are already at it, with Act party leader David Seymour already loftily declaring that we need to stop focusing on climate change mitigation.

“Our climate change response needs to shift from mitigation to adaption. New Zealand can’t change the climate but it can better adapt, and unfortunately we’re getting a really big lesson in that right now,” Seymour said.

This is, of course, unmitigated bullshit. New Zealand has both internationally agreed and profound moral obligations to mitigate climate change, especially given we are the world’s sixth greatest emitter of greenhouse gases, per capita. But, more to the point, if the world doesn’t mitigate climate change, it will create a catastrophe that’s impossible to adapt to.

On that note, let’s keep looking into who’s responsible for our lack of both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Last post, I detailed who some of New Zealand’s merchants of climate doubt are. The following post — copied with permission from No Right Turn — shows just how successful they’ve been.

Climate change: The lost decades

Originally posted 15 February 2023 at No Right Turn

Over the last few days Aotearoa was hit by ex-tropical cyclone Gabrielle – the second tropical cyclone to hit us in just two months. Huge chunks of the country have been flooded, 225,000 people have lost electricity (some will be without it for two weeks), and at least two people are dead. The economic impact is estimated in the tens of billions. Before Parliament adjourned so MPs could go and help their constituents, Climate Minister James Shaw gave a speech drawing the obvious link to climate change [video], and warning that we are now entering “a period of consequences”:

I have to say that, as I stand here today, I struggle to find words to express what I am thinking and feeling about this particular crisis. I don’t think I’ve ever felt as sad or as angry about the lost decades that we spent bickering and arguing about whether climate change was real or not, whether it was caused by humans or not, whether it was bad or not, whether we should do something about it or not, because it is clearly here now, and if we do not act, it will get worse.

I’ve been recalling, actually, a quote from a different time about a different crisis: “The era of procrastination, of half measures, of soothing and baffling expedience of delays, is coming to its close. In its place we are entering a period of consequences.” And there will be people who say, you know—just as the National Rifle Association in the United States does about shootings over there—it’s “too soon” to talk about these things, but we are standing in it right now. This is a climate change – related event. The severity of it, of course, made worse by the fact that our global temperatures have already increased by 1.1 degrees. We need to stop making excuses for inaction. We cannot put our heads in the sand when the beach is flooding. We must act now.

Newsroom‘s Marc Daalder has talked about this period of consequences – or, as he put it, Alt title: Fuck around and find out. But I’d like to look at the “fucking around” part. Because there is a lot here to be angry about, and people we need to hold to account.

Way back in 1992, the then-National government endorsed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, in which they promised to reduce emissions. They followed this up in 1998 by signing the Kyoto Protocol, committing us to a binding emissions reduction target. Environment Minister Simon Upton did a lot of work, developing a fully-formed, all-gases, all-sectors emissions trading scheme, but his National colleagues – farmers and climate-change deniers – fucked around, chickening out of implementing it at the last minute, leaving the problem for future governments.

In 2002 the then-Labour government ratified the Kyoto Protocol. They then fucked around, switching from an ETS to a carbon tax and then dumping it under pressure from their coalition partners. They chickened out of making farmers pay a minimal levy on agricultural emissions, while repealing existing regulatory solutions to reduce emissions in favour of a “perfect” price mechanism which didn’t exist yet. They then switched back to a partial emissions trading scheme (wasting another three years in policy development), which they loaded with pollution subsidies and opt-outs, and did not pass until literally the last days of their term. It was then immediately gutted by National.

Not content with gutting the ETS, the new National government elected in 2008 set up a “review” of climate change policy packed with climate change deniers to undermine policy even further, while repealing the thermal electricity ban and biofuels obligation. They then gutted the ETS even more, adding even more subsidies for polluters. At the same time, they announced a “50% by 2050” emissions reduction target, and ratified the Paris agreement. But they fucked around, and did nothing to meet their obligations.

In 2017, then-Labour leader Jacinda Ardern called climate change “my generation’s nuclear free moment”. In 2019 the government she led passed the Zero Carbon Act, ostensibly committing us to long-term emissions reductions, with plans, budgets, reviews, and all manner of bureaucratic bullshit. And then they fucked around, repeatedly fucking with the carbon market to keep carbon prices low, repeatedly delaying making agricultural polluters pay for their pollution (and then only at the lowest possible level), and introducing even more subsidies for polluters. They’ve now pissed all over their carbon budget by subsidising petrol.

All of these governments fucked around. There’s a common theme of hard-working climate ministers – Simon Upton, Pete Hodgson, and James Shaw – being betrayed by their Cabinet colleagues and having their plans dumped (Nick Smith is a malignant exception to this, being a collaborator with climate change deniers). There’s another of constantly grovelling to farmers, a dirty, inefficient sector which receives more in subsidies than it pays in taxes, and which when you factor in the costs of its pollution, seems to be a net drain on New Zealand. And there’s a common theme of them viewing climate change as a problem for the future, a mess they can leave for someone else to clean up. The consequences of that irresponsible short-term thinking can be seen on the East Coast today.

They all fucked around, and we’re now finding out. And the people who fucked around got knighthoods and big pensions and posh post-political careers with banks and SOEs and crown entities. They got rich, while kiwis got flooded and left in the dark. And it’s time we held them accountable for it.

Can we stop calling deniers “sceptics” now please

Pretty hard to be skeptical of this. Me again. Thanks again to Idiot/Savant for permission to reproduce his post. Please check out No Right Turn; it’s one of New Zealand’s best political blogs.

In related news, journalist Charlie Mitchell is one of Stuff’s most consistently excellent writers and he has a great piece on denial that I encourage you to check out, but that I also take some issue with. Mitchell correctly identifies the role of mainstream media opinionists in driving false narratives about the cyclone and climate change, but he calls this phenomenon “Cyclone Gabrielle scepticism.” It’s part of a long media tradition of calling climate change deniers “climate sceptics,” when they’re anything but.

A sceptic (also spelled skeptic, which I like better for some reason, so I’ll just use that from now on) is someone who suspends belief in any dogma that lacks evidence. Essentially, skepticism is the thinking behind the scientific method. The idea of climate change deniers being skeptics is a joke, as the scientific evidence for human-caused climate change is overwhelming. And if you’re feeling, uh, skeptical, here are the NZ Skeptics on climate change, forced to make a clarification because of misidentification with so-called “climate skeptics:”

The New Zealand Skeptics Society supports the scientific consensus on Climate Change. There is an abundance of evidence demonstrating global mean temperatures are rising, and that humans have had a considerable impact on the natural rate of change. The Society will adjust its position with the scientific consensus.

The news media should stop using “climate skeptic” and similar terms immediately. It confers climate change deniers a legitimacy they really shouldn’t enjoy, as they are demonstrably following a dogma rather than engaging in critical thinking. If they’re looking for a more accurate term, they could simply use “climate change deniers” or if that’s too on-the-nose, why not settle for “climate cynics?”

Thank you for reading The Bad News Letter. If you want to see climate change denial out of our media, please share this piece.

Voices for Climate?

Thanks for the discussion that took place under the last post. A particular shout-out to Tamara who wondered if there could be some kind of “Voices for Climate” who could fight against climate disinformation disseminated via the media. Bloody good idea. I was less stoked to see someone trying to sneak in some climate doomism. Just no. I’m about as tolerant of doom as I am of denial. It’s unscientific and unhelpful, as it drives decent people to despair and helps provide a perverse “well, if we’re all screwed, we may as well keep drilling” social license to the fossil fuel industry. But it’s quite different from expressions of sadness or even despair, which are entirely fine, especially now we find ourselves firmly in the “finding out” stage of climate change. If you feel the need to vent, go for it.

And now, a word from the future’s sponsors

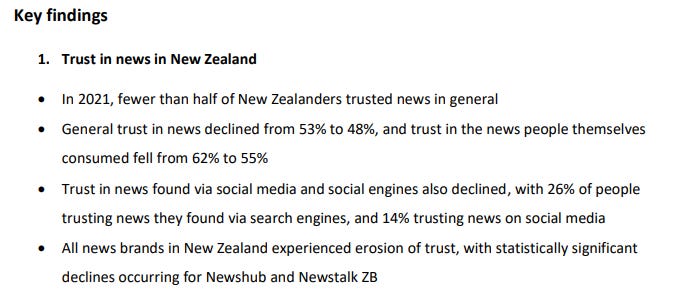

In the aftermath of the Auckland floods and the still-unfolding catastrophe of Cyclone Gabrielle, the media are asking whether New Zealanders (correctly) see these events as linked to climate change. “Does Cyclone Gabrielle have you thinking about climate change? You’re not the only one,” writes the excellent Kirsty Johnston, at Stuff.

These articles always seem to crop up after climate disasters, and as climate change intensifies, we’re seeing them more and more frequently. In them, the physical processes behind climate change are usually outlined accurately, in some detail. Where they fall down is the human causes. In all these pieces is a missing piece: the identification of those most responsible for climate change. They often offer a vague “we” to identify those causing emissions — which is technically correct, in the same sense as the statement “we humans cause war” — and then suggest “changes at an individual level” that can help too.

But it’s not just “we”. The main cause of climate change is emissions from fossil fuel use and agriculture. And the main proponents of the agricultural and fossil fuel industries in NZ are specific people, with names and job descriptions, who lead or belong to organisations who work to delay meaningful climate change action. In this opposition, they too bear an outsize share of the responsibility — for not only the damage climate change has caused, but the far greater damage it will inflict in the future.

In “Will this be the climate crisis that finally spurs action?” economist Bernard Hickey, writing for The Spinoff (syndicated from his fantastic newsletter The Kaka) correctly points out that the current Labour government should shoulder blame for failing to use their absolute majority in Parliament to take action on climate. But as insightful as it is, this article doesn’t mention the ongoing influence campaign against meaningful climate action, conducted almost entirely by right-wing political parties and think-tanks, often in service to agricultural and fossil fuel interests — who frequently work together as one big team.

I feel like that’s a gap that needs filling.

They are Federated Farmers, who have for years successfully opposed meaningful climate action on New Zealand’s greatest source of emissions: agriculture.

Their CEO is Terry Copeland.

They are the Taxpayers Union, who are not a union, and who have an intentionally opaque funding structure that allows them to (im)plausibly deny that they are funded by fossil fuel and tobacco interests, among others. The Taxpayer’s Union is a member of the international Atlas Network, an association of right-wing think-tanks sponsored by the likes of the Koch Brother (formerly known as the Koch Brothers, before one of them went to his post-death reward). This fake union’s hobby is gaming news media by chundering a vast quantity of press releases on contentious topics that editors find irresistible and, in partnership with David Farrar’s polling firm Curia, undertaking expensive political polling activities. They indulge in a form of soft climate change denial, where they weaponise insights gleaned from Curia polling and focus groups to whip up public rage and resentment against climate-friendly projects like cycleways. It is my sad duty to report that they have a podcast, hosted by climate change denier Peter Williams. In its latest, dire episode, it was graced by Federated Farmers’ Mark Hooper and Paul Melville. (In a classic Kiwi 2-degrees-of-seperation twist, I went to Uni with Paul.) His position is Principal Advisor, Water & Environment Strategy. One wonders what his principal advice is, given that dairy farming has ruined New Zealand’s waterways and filled our groundwater with bowel-cancer-linked nitrates.

The director of the Taxpayer’s Union is Jordan Williams, who is perhaps best understood by an opinion uncovered in Nicky Hager’s The Hollow Men: “women: if they didn’t have a fanny between their legs they’d have a bounty on their heads.” Their co-founder is David Farrar, a long-time National Party operative and pollster and fellow star of The Hollow Men.

They are the Act Party, who indulged in outright climate denial for years and now advocate for renewed offshore oil and gas exploration in New Zealand and for the wholesale repeal of the Zero Carbon Act.

The leader of the Act Party is David Seymour.

They are the National Party, who oppose meaningful emissions reduction policies in agriculture and who, along with Act, have sworn they will repeal the New Zealand offshore oil and gas exploration ban.

The leader of the National Party is Christopher Luxon.

They are the New Zealand Initiative, who advocate strenuously against all forms of climate action except the Emission Trading Scheme. (Emissions trading schemes are dubiously effective, and at worst are scams designed to allow the worst polluters to pollute indefinitely.) They too are members of the right-wing, Koch-funded Atlas Network. They too published outright climate change denial for years, and are now wrongly portraying all non-ETS-based climate action as ineffective.

The head of the New Zealand Initiative is Oliver Hartwitch. The chief economist for the New Zealand Initiative is Eric Crampton, who hews to the Austrian / Chicago Boys school of freemarketism and is frequently given a platform by New Zealand media. The author of the Initiative’s Pretence of Necessity report, economist Matt Burgess, is now Chief Policy Advisor to National Party Leader, Chris Luxon. Luke Malpass, who is Stuff’s political editor, formerly worked with the Initiative, helping them right back at their origin — a merger between the New Zealand Institute and the much-loathed Business Roundtable. Here he is working for the Initiative, before he grew his cool hipster moustache and got a job at Stuff sneering at “lockdown lefties“.

They are Energy Resources Aotearoa, a fossil fuel lobby and greenwashing group who recently changed their name from the deeply unfashionable yet far more accurate PEPANZ (Petroleum Exploration and Production Association of New Zealand). They lobby against restrictions on fossil fuel exploration and production in New Zealand.

Their Chief Executive is John Carnegie. Their communications manager is the fascinatingly-named Ben Craven, formerly of the Taxpayer’s Union.

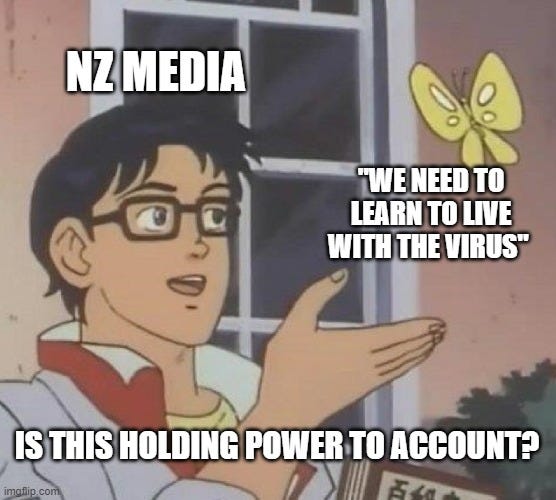

They are NZME, who intentionally and cynically give climate change minimisers, doubters and delayers like Mike Hosking and Heather du Plessis-Allan a rarefied platform to foment conflict and garner listeners by promoting disinformation about renewable energy and climate adaptation and manufacturing consent for the continued and expanded operations of the fossil fuel industry.

HDPA, 14 February 2023: “So yeah, for a lot of people, I reckon this will be the final piece they need to convince them something needs to be done….. Not so much that they need to give up their fossil-fuelled cars, because come on, we all know NZ isn’t going to do much to change global emissions.”

Mike Hosking, 10 February 2023: “The theory was we would use EV’s and batteries and solar and wind and sunflower seeds. But the reality is none of those things are reliable enough or available enough. As they currently stand, they aren’t actual answers. They are alternatives of a temporary nature and, given that, there is no point in getting all angsty about profits and wanting to put a windfall tax on them that is talked about… The zealots are asking us to do something we won’t do, which is go backwards. We will not do it and we are not doing it. Our reality, and its smooth operation, will trump ideology every time.”

Oh and just for fun here is fellow NZME stable-mate and wife of Mike Hosking, Kate Hawkesby, indulging in some deeply unfortunate pre-catastrophe amateur meteorology on Instagram.

I hope the fact that Hawkesby deleted this post means she now understands what “calm before the storm” means. The CEO of NZME is Michael Boggs. Its Managing Editor is Shayne Currie.

This is not an exhaustive list. There are plenty more.

These organisations, the people who staff them, and the people who run them, are — whether they outright admit it or not — advocates for continued agricultural emissions, for the continued use of fossil fuels, and the further expansion of the fossil fuel industry. They are merchants of doubt who seed climate delay propaganda, using their enormous resources and platforms to sway New Zealanders against climate action.

This is far worse than the climate change denial of the past. Now that the causes and effects of climate change are impossible to deny, and the coming ravages are clear, these people are committing a far greater evil. They know exactly how destructive climate change already is, and yet they act to make it much worse.

So, name them. Blame them.

An outsize share of future climate catastrophes are their fault, and they must be held accountable.

“Will this be the crisis that finally spurs action on climate change denial?”

It’d be nice if it was, wouldn’t it? A silver lining to the raging cloud the size of half a continent that darkened our skies over the previous week, destroying the livelihoods of thousands. Let’s look at how it could work:

Think tanks

The climate-delay-advocating think tanks work by injecting their message into the media, and from there it is carried to the public. While they do have some public following via social media, the think tanks still overwhelmingly rely on mainstream media manipulation to get their message out. This could be stopped if news media simply agreed to stop platforming people who seek to delay climate change action. When it is necessary — for genuine newsworthiness reasons — to report on a fossil-fuel-affiliated, climate-change-delaying think tank, the piece can be accompanied by heavy disclaimers identifying the known affiliations and motivations of the think tank. As a bonus, it would mean that we would never, or hardly ever, have to hear from that fake union of people who object to even the concept of taxes.

Political parties

On the surface, this is much trickier. Although climate inaction stands to displace, ruin, or outright kill billions of people in the not-particularly-distant future, parties that deal in climate delay or soft denial are still seen as politically legitimate. But this is a flaw in the media lens; journalists and editors could quite easily start telling the truth, which is that failing to mitigate and adapt to climate change is both economically expensive and morally unconscionable. I imagine that in this near future, we may see climate deniers and delayers a bit like we view Nazis now; as wholly illegitimate parasites on the body politic. As things stand, vowing to re-open offshore oil and gas exploration is viewed not as a crime against the future of humanity but in terms of “you may not like it, but it’s smart politics.” Political journalists should not simply repeat what politicians say and assign points; they should frame the statements of politicians by how well they relate to observable reality. In other words, they should tell the truth. Let’s see how that could work in practice, with this story from the Herald. Here’s how it reads currently:

Christopher Luxon has reaffirmed National’s policy of overturning the ban on issuing new permits for offshore oil and gas exploration, saying it is a solution to New Zealand’s energy crisis.

Luxon said gas could be used as a bridging fuel, and said the Government should scrap its 2018 decision to stop issuing permits for oil and gas exploration offshore.

And here’s how it could read if political journalists were interested in reporting reality:

Christopher Luxon has reaffirmed National’s policy of overturning the ban on issuing new permits for offshore oil and gas exploration, saying it is a solution to New Zealand’s energy crisis. However, scientists and expert bodies such as the International Energy Agency say that no new fossil fuel extraction can be carried out if the world is to stay within Paris Agreement goals of 1.5 degrees C of warming.

Luxon said gas could be used as a bridging fuel, and said the Government should scrap its 2018 decision to stop issuing permits for oil and gas exploration offshore. However, the IPCC has made clear that practically all fossil fuel use must stop in order to avoid catastrophic climate change, and the notion of a “bridging fuel” is simply a fossil fuel industry talking point.

There. FTFY. There’s much more to write on the way that political journalism adopts a frame wherein politics is scored like a cricket match, and policies are praised or decried only in terms of how well journalists predict the public will perceive them, but that can wait. In the meantime, the public should demand that the media simply stop legitimising climate change delay and denial.

Media

Here’s an easy one: stop taking fossil fuel industry advertising money and running fossil fuel industry ads. Done.

This will probably not happen overnight, but for meaningful change to occur, it has to. It’s time we demanded it.

Thank you for reading The Bad News Letter. This post is public so feel free to share it.

If you found this newsletter valuable, please share it

These things aren’t easy to write, and they occasionally seem to upset powerful people, which — as fun as it sounds — can make life pretty difficult. Your support, whether through sharing this article, or a paid subscription if you’re financially able, is much appreciated.

On a personal note

Gidday. So this is more of a personal note than anything, and those that read David Farrier’s Webworm (which is probably a lot of you, and if you don’t, start! It’s great!) are probably already aware of it. But for those that aren’t, here’s the gist: I’m starting a new project called The Cynic’s Guide To Self-Improvement and I’d love to have you as a subscriber.

But wait! you think, in an agony of indecision and betrayal, you’ve already got this newsletter! The one I’m reading right now! And you already hardly ever update it! How will another project improve the situation?

Well, disembodied voice, you make a number of good points. But here’s the thing. The idea of my self-improvement project is — as well as shining a light on the weird, grift-ridden and occasionally life-ruining world of self-help — to improve my self. Much of what I’d like to improve is my consistency; I’d like to make more art, and do more writing, and publish more regularly. Some of that writing I’d like to go here.

News media ethics is something that, for my sins, I still care very much about. It’s also a difficult and depressing subject to deal with. Writing about the media — especially when it’s stocked with journalists, some of whom are good friends, and nearly all who are doing their best and who individually cannot do much about the systemic failures facing the hallowed Fourth Estate — is hard to do well. And reading Newstalk ZB columns does not spark joy.

All that said, I think it’s an important subject to return to, and I’d like to do so. For the Bad Newsletter, I’m pretty sure I can manage one post a month at minimum. The Cynic’s Guide will update more frequently, at least once a week. It will be a tricky cadence to manage, but if I can do so, I’ll have proved something important to myself, and possibly also to you.

So I’d like to say a very sincere thanks for sticking with me so far. To those who took out paid subscriptions, I appreciate the vote of confidence more than I can really put into words.

So yeah. Hang around, if that works for you. There’ll be more media and media-adjacent Bad News coming soon. In the next one, we will look at the origin stories of someone that everyone’s definitely not sick of hearing about endlessly: Elon Musk.

Subscribe to the Cynic’s Guide To Self Improvement here.

Among Us: the too-close-to home terror of Mister Organ

The reviews all seem to agree: Mister Organ, the newest film from journalist David Farrier, is disturbing. It’s strange. It’s unsettling. It’s funny. It’s very, very good. Having seen it myself at a Q&A screening last night, I can definitely attest to how creepy the film is. But the depth of the creepiness — and the genius of the film — goes a lot further than it’s easy to explain in a normal review, so I’m going to try another way.

Among Us

A few years ago, long enough now that distance has taken the bleeding edges off the event, my mum and stepdad got in some terrible trouble. At the time, they lived on Russell Island in Moreton Bay, near Brisbane. The island is, and remains, one of the strangest places I have ever been. I’ll write about it at length, one day. For now, it’s enough to say that despite many promises and plans, Russell Island has never had a bridge to the mainland. The only way to get there is by ferry, and this inconvenience meant real-estate prices on the island weren’t soaring the way they were elsewhere around Brisbane and the Gold Coast. Mum and her partner were desperate to sell their house, another piece of land they owned on the island, and get away before prices on the mainland got too far out of reach. And one day, they met someone who said he could help.

His name was Zach Mar, and he — with some help from a local woman — had created a scheme called Display Partners. The idea was, very loosely, that you’d give Display Partners money, and they’d work with a builder who’d use your investment to build a display home, at a very low cost. The builder would rent the home from you and show it to potential clients, and after a few years, you’d have a beautiful home that you could move in to or rent.

A screenshot of the defunct Display Partners site, as archived by the Wayback Machine. Just look how happy those stock footage models are! Sounds good, right?

Perhaps a little too good?

You know where this is going.

I only found out about my mum’s involvement with Display Partners through unnerved reports from my brothers, and Mum’s own Facebook posts. Those were the first warning signs. When I asked her about it she was uncharacteristically cagey. Something seemed off, so I got digging.

A year or few earlier, I’d picked up some odd skills from hanging around a motley group of people I knew online and IRL. We’d recently become obsessed with a rapidly-deepening rabbit hole on the topic of “Competitive Endurance Tickling.” Comprised of David Farrier, Dylan Reeve, me, and a several other people, the Tickle Friends would unearth a lot of the material that ended up in the documentary Tickled. Now, I put what I’d learned about internet sleuthing to use, prying into Display Partners.

I learned that Zach Mar aspired to a playboy lifestyle, with a yacht and other rich-guy amenities, and that he ran charity events for disabled children. That he’d only recently arrived in the Bay Islands, that he’d convinced many people into investing in Display Partners. That he used several other names, all variations on the Zach Mar theme, and that no-one seemed to know who he really was or where he came from.

And I found that he’d run real estate scams all over Australia.

I was terrified for my mum. I let my brothers know what I’d found and called her. To my dismay, she was angry, and distant. She implied that I didn’t trust anyone, that she’d known I would try to interfere. But during the call she let slip that my sister and her partner had got involved. The idea was that Zach, a real-estate genius, would help them buy a house.

I nearly booked a ticket to Australia on the spot, which would have taken all the money I had at the time. Instead, I called my sister, who didn’t sound pleased either.

“They’re just helping us buy a house!” she said. “Zach knows so much about it, you should hear him talk. He knows a way we can do it without having to pay all this money up front.”

“That’s fine!” I said. “If he’s just helping you get through the process of buying a house, there’s no trouble! The important thing is that you don’t try to get around the law, or give him any money up front.”

My sister went silent.

“Have you given him any money?”

She didn’t say anything. I panicked.

“These people are evil!” I yelled. “They’re scammers. Don’t give them a single cent. If you give them money, you’re going to lose it all! You have to believe me!”

I shed a few angry tears after the call. I didn’t know what else to do. I was sure my sister had given these people her money, and that they would steal it. But what if I was wrong and had wildly overreacted, slandering someone who was actually trying to help my sister out?

It wasn’t until months later, when I finally made it over to Australia for a visit, that I learned what had happened.

My sister had indeed trusted the people behind Display Partners with some money. After another panicked call, this time from my brother, my sister got in touch with the woman Zach Mar was working with, and demanded the money back.

That wouldn’t be possible, the woman said.

I wasn’t present, but I know what happened next. I’d witnessed my sister get properly angry a few times as a kid. I was older than her by two years, but I got the hell out of the way when it happened. She turned into a fucking Valkyrie, all ice and fury and razor edges.

She told the woman that if the money wasn’t back in her account by the following morning, they’d be hearing from her workplace’s extremely competent and high-priced lawyers. She hung up.

The money was back in her and her partner’s account by the deadline. The amount: their life savings. An entire house deposit.

This event was a domino that helped topple the Display Partners scam, as it did indeed turn out to be. I could go on for a whole documentary’s worth of madness and skullduggery, but I’ll just give you the finale. My mum couldn’t brook the threat to her daughter and told Display Partners she wanted out too. They turned nasty. Battle lines were drawn: believers versus skeptics, with believers terrified that the scrutiny from skeptics would torpedo their investments. The tight island community seethed at each other. Lawyers, journalists, state officials, and detectives all got involved.

Mum and her partner eventually got out, having lost a few thousand dollars. They escaped with some of their savings, and their house. Others were not so lucky. A number of people — mostly older, mostly retired — lost everything they had.

Afterward, my family and I put things together again. My sister was grateful. My mum was too, but she and her partner felt terrible shame over the episode. “We just feel so stupid,” her partner told me. But they weren’t. They were trustworthy, kind people, which made them think other people would be trustworthy too. The scammers took full advantage.

Zach Mar disappeared.

Despite some real effort, I never managed to speak to Zach or see him in person. After he vanished, the closest we got to closure was a rumour that he’d crossed the wrong people and got beaten to a barely-alive pulp. Hearing this made me feel sick. I wanted to see him pay, but not like that. Real life is messy. It doesn’t often offer satisfying endings.

I’d always meant to write a proper story about this, but for a long time it felt too close. Gradually, I let it go, along with the thought of writing it up. Then I watched Mister Organ, and it brought the whole terrible episode roaring back.

You don’t just watch Mister Organ. The character is described as a void, and that’s the thing with voids: they watch you right back. Don’t misunderstand — the film is really funny, full of the kind of odd folly that can’t help but make you crack up. It got more audience laughs than a lot of comedies. But it stays with you in a way that’s not comfortable. Leaving the theatre, I felt like I’d come away from Mister Organ with a little bit of Michael Organ in my head. Lurking, peering, giggling, talking.

It’s not a spoiler to say that Michael Organ talks a lot. Like, three hours at a time, without stopping. Of course, this isn’t in the film, which lasts a swift 95 minutes. (At the Q&A, I was tempted to ask if there’d be a DVD extra that’s just footage of Michael Organ talking non-stop, for three hours. David, if you’re reading this, this is a really good idea and you should do it.)

The talking at length thing fascinated me. After the film, I thought about all the other times I’d seen similar behaviour. Marketing copy for sketchy products on weird websites that go on forever. The endless screeds of QAnon and anti-vax conspiracy theorists. The droning babble of scammy pastors and preachers. “Nigerian” 419 scam emails filled with capslock and dubious claims of royalty. Tickled star David D’Amato’s ranting, furious, constant emails, and the many websites he created, full of wild claims and slander.

Talking at length in this way is not just something that scammers do because they love the sound of their own voices (although that’s part of it). Dismissing it as ranting is a mistake, because con-artists do it for a reason. If you find yourself being talked at in this way, there is a chance you are a mark. You are being tested, probed, winnowed. 419 scam emails are long and loaded with nonsense to filter out skeptics. If you still maintain any belief by the end of one of their rambling screeds, they’ve got you. Even if you’ve never read a scam email, you’ve seen this behaviour before — in the strange, rambling, self-obsessed droning of the incredibly dangerous narcissist who starred in The Apprentice and would later serve time as the 45th President of the United States.

Zac Mar loved to talk too, my mum told me. He’d come and drink her tea and coffee and talk and talk and talk. The people he preyed on thought he was a real-estate genius who was going to either help take away their troubles, or make them some much-needed money. Mister Organ reminds me of him, and of the fact that there are Mister Organs everywhere.

It’s this that makes Mister Organ the most powerful film I’ve watched in a long time. Everyone should see it. It’s a case study in disturbance, and an explainer on how dangerous people operate, how they prey on others. How they’re so hard to pin down, so hard to stop. It’s also a brilliant example of journalism done right, of its remarkable power to shine a light in dark places, to protect the innocent, to give dignity to victims — and to warn the unwary.

I wish the film had come out ten years ago, and that my mum had seen it back then. Witnessing Organ’s tactics and the effect he has on other people might have saved her a world of hurt. Instead, I’ll settle for telling you to watch Mister Organ as soon as you can.

Find session times and buy tickets for Mr Organ at flicks.co.nz.

The Problem(s) With Twitter

I’ve been on Mastodon for about five minutes now and it’s safe to say I like what I’ve seen.

Of course, because it’s Mastodon, I’m not on “Mastodon.” That’s like saying “I’m on email.” As far as I can tell, Mastodon is just the protocol for a whole bunch of different social networks that can all talk to each other. I’m on mastodon.nz, which looks like a good, welcoming community. It’s raw, a bit clunky, scattershot, off-kilter. Already, it’s striking how different it feels from Twitter, or at least, what Twitter has become.

I never really fit in on what everyone is now calling “the bird app.” It became clear, pretty quickly, what you needed to become big on Twitter. If you had a following from outside the app, like being an author or a Kardashian, it was easy enough. Or if you had a specialism, like actual deep science or tech knowledge, your following tended to aggregate around those wellsprings of knowledge. But to become a big deal on Twitter via Twitter itself, you needed to Post. You needed to adopt a personality or posting archetype and double down on it. A lot of the time, the personality adopted was, well, kind of horrible, or at least it was in the political and journalism circles I followed. An post-ironic, world-weary, ultra-supercilious personality dominated. Permanently angry, yet arch and distant. You could be mad about stuff at the same time that you were flippantly dismissing everyone else who was actually mad about it because, You, the Poster, were Above All That.

I didn’t like it but at the same time, it molded my online personality. It affected everything and everyone on Twitter. If you wanted your stuff to get seen, you had to Post, and even if you were genuinely earnest or enthused about something, the precedent of coating it under pearlescent layers of post-irony was almost unavoidable.

And then there’s the other kind of Poster, which is the sort that finds the worst stuff in the world and signal-boosts it for clout.

It’s an understandable instinct. We all want to avoid being associated with bad out-groups, right? And to know who the bad out-groups are so we can avoid them? And of course journalism is often highlighting bad things. But, importantly, journalism offers context — or at least, it does when it’s done right. On Twitter, simple virtue-signalling was immediately weaponized, often by sociopaths who recognized that outrage was a perfect path to acquiring a following. They made great use of it. For a while, I tried to spend my time online suggesting that signal-boosting your political and ideological enemies was wildly counter-productive, but this was never popular. People just got mad at me. “But this guy! Look how bad he is! Look at the terrible thing he just said! No-one should have to see this! I’m going to show it to everyone!” Arguably, this behaviour is what ultimately gifted the world President Trump. On New Zealand Twitter, with its blessedly lower stakes, look-at-this cloutposting reached its nadir when terminally online lefties started screenshot-mocking the National Party social media pages for making memes incorrectly.

They’d been played. National, utilizing the either the services or the tactics of Tory-friendly agency Topham Guerin, was committing design crimes like poorly-labelled graph axes or using uncool fonts specifically to wind up terminally online lefties who would then signal boost their political ads for free. It was brilliant. Instead of articulating their actual ideas or values, which might win allies, an online army of lefties had been deputized as water-carriers for their own opposition.

One of the reasons I like Mastodon is because there are specific mechanisms and server rules that might help to disincentivize this infuriating, self-defeating habit. For example — with the obvious disclaimer that I am new and don’t know much about how it works yet — it seems that on mastodon.nz, you’re encouraged to hashtag political stuff, or chuck a content warning on it. It’s about choice. If using hashtags is standard, users can filter out stuff they can’t be bothered with, or specifically zero in on it. If very specific content warnings for controversial content that go beyond just “NSFW” are normalized, it’s always up to a user whether they want to see it. It might finally be an end to oh my god, this stuff is disgusting! Let’s show the world!

The federated nature of Mastodon instances is also looking like a real boon. In the Dawn of Everything which has become my “no, really, you absolutely must read this, ideally yesterday, but I’ll settle for right now, look, here are some bits I’ve highlighted or memorized” book of the moment, authors David Graeber and David Wengrow make the case that indigenous societies in pre-colonization North America featured vastly more social mobility than our world does today. There was constant, radical experimentation and flux across different nations or tribes. If you didn’t like the way a given nation did things, that was (often) fine. You could leave, and find a new nation that was more to your liking. The authors suggest this happened frequently, and that, fascinatingly, many indigenous people traveled far further than it’s common for people to do today. Then the hegemonizing, colonizing forces arrived. There was now one way to do things and you couldn’t leave. My way, without so much as a highway. In Margeret Thatcher’s infamous words: there is no alternative.

Just like we’ve got used to living in extremely similar nation-states where we can’t easily experiment with new ways of doing things, we’ve become inured to an Internet world where there is no alternative. The corporate consolidation of the Internet has given rise to an often-joked-about status quo (posted, of course, on Twitter).

I’m old enough to remember when the Internet wasn’t a group of five websites, each consisting of screenshots of text from the other four.

— Tom Eastman (parody) (@tveastman) 7:28 PM ∙ Dec 3, 2018

We’ve all become used to how bad Twitter is, like frogs broiled in a collective pot of Posting. It’s taken Musk’s terribly-executed takeover as Main Character-in-Chief to shock a lot of us into looking for an alternative. Plenty of people, including me, had already drifted away. I’d deleted the app on my phone and only dropped in occasionally on the web interface where adblockers and other plugins made the experience sporadically tolerable. But now, instead of drifting apathy, there’s a real mood to look for alternatives.

Naturally, people are worried about what that might entail. I’ve seen prolific Twitter users who use the platform to advertise their livelihood worry that their reach will be circumvented on a federated platform like Mastodon. And that’s understandable, but you also need to know that if you were on any of the big platforms, your reach was already being artificially curtailed. If you built a platform on a Meta property, like Facebook and Instagram, your ship sailed a long time ago. Want people to see your stuff? Pay up. The last major platforms where unmonetized virality is possible are YouTube, Reddit, and TikTok (and, email, sort of). YouTube is already a morass of a few top creators trying ever more desperately to game the algorithm and trust me, you’re not as good as they are. Also, making videos is hard. Reddit is a double-edged sword: it sometimes works for creators who need to be discovered, but the site’s culture and moderators have an inherent, bizarre hostility to creators sharing their own stuff. These rules are enforced sporadically and the fate of your self-promotion will often fall to the whims of whoever is modding a particular subreddit on a given day. Redditors moan constantly about a lack of original content, somehow missing the point that much of the site has rules against posting original content. If you make stuff, your best bet for being seen on Reddit is for one of the site’s many semi-professional content thieves to steal it, post it without consent or attribution, and for someone in the comments to recognize it and drop a link to your Instagram or YouTube.

I have no idea what the deal with TikTok is. I’m too old for that shit.

But if you are a creator on Twitter, chances are your reach has been bounded for a long time. No matter how many followers you supposedly had, if you were posting there, your content was being algorithmically curated, and was probably being shared and signal boosted by one small set of people who the algorithm had pegged as liking your stuff. If you that set was big enough, you were probably doing fine, but if not, well. Unless you are a very successful Poster, you have probably got nothing to lose by going to Mastodon, where the lines designating the borders of different communities are clear, instead of invisible and arbitrarily enforced by proprietary algorithm. A small audience that’s 80 percent engaged is, potentially, much better than a large audience that isn’t engaged at all.

I’m not sure why I’m writing this screed, which has turned into more of a missive, or possibly even a treatise. I suppose it’s because discovering Mastodon has me wanting to write and share stuff again. The idea that there might be an audience (however small) that is interested in anti-inflammatory discussion of the things I’m interested in is intoxicating. I love the idea of making things without feeling like my creativity is being invisibly shaped by algorithmic necessity, the thought that I can post without Posting. I have this FDR quote knocking around in my head: “Bold, persistent experimentation,” and the feeling that it’s what I need, what the internet needs, and what the wider world could do with. It feels like there’s once again a welcoming wall against which I can throw stuff, and see if anything sticks.

At last, there is an alternative. But not just one. There are lots of them.

See you there. And also here.

Needless F****** Things

I’ve always wanted to make a living as an artist, but so far, life hasn’t found a way.

What’s frustrating is not that I’ve had no success; it’s that I’ve had some. Just enough for a taste. When I marshal my scattered attention for long enough, I can mix my humour and limited painting ability into some weird blends that people seem to genuinely dig and that I’m still proud of.

Over several years, I painted and auctioned weird portraits of New Zealand politicians the rest of the world is lucky enough not to know about, which went a tiny bit viral. Partly because of this, I managed to finagle a place at an illustration convention called Chromacon. The only problem was that I didn’t have much to exhibit.

Birds with Hats:

What to paint? I like birds, but I needed to differentiate myself from hundreds of other Kiwi artists who like birds too. I also like Lord of the Rings, and silly puns. As an experiment, I painted a Riroriro (Grey Warbler) wearing a wizard hat, and called it Gandalf the Grey Warbler.

I enjoyed the joke and the painting so much I did three more just like it, quadrupling my last five years or so of art output in about two weeks. I got some prints and an online shop made in time for the exhibition, and as an afterthought, I put some pics up on Reddit. My post got popular enough that quite a few people bought prints. Success!

A real live human:

Josh’s latest creation – a human child! A few years later, having painted several more birds, I started a YouTube channel where I painted scenes from video games using techniques learned from watching living meme Bob Ross. This was just starting to get a bit of traction when my wife and I received my best excuse yet for not making art: a baby. I didn’t paint or draw anything for about 12 months — until David asked me to do some illustrations for the Webworm I wrote about climate change.

That’s most of the highlights from the last ten years. While it’s fair to say there’s been some success on the art front, my artistic inconsistency — plus the opportunity cost of leaving a job that pays for one that mostly doesn’t — have tanked the idea of doing art full-time.

So when I saw a Webworm article on how some artists were making a living from NFTs, I was genuinely interested.

The only problem was that NFTs are built with the same technology that powers cryptocurrency. And I know just enough about crypto to hate it.

Pollution, monetized

To my mind, cryptocurrency is explained most brilliantly by The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy. Typically, author Douglas Adams managed to do this despite having died eight years before Bitcoin first appeared. The scene: a bunch of humanoid aliens (comprised of the “useless third” of their planet’s population, which includes marketers, management consultants, and documentary makers) have crash-landed on prehistoric Planet Earth and are looking to set up a new society. Here, let me plagiarise:

“If,” the management consultant said tersely, “we could for a moment move on to the subject of fiscal policy. Since we decided a few weeks ago to adopt the leaf as legal tender, we have, of course, all become immensely rich.”

Ford stared in disbelief at the crowd who were murmuring appreciatively at this and greedily fingering the wads of leaves with which their tracksuits were stuffed.

“But we have also,” continued the management consultant, “run into a small inflation problem on account of the high level of leaf availability, which means that, I gather, the current going rate has something like three deciduous forests buying one ship’s peanut.”

Murmurs of alarm came from the crowd. The management consultant waved them down. “So in order to obviate this problem,” he continued, “and effectively revalue the leaf, we are about to embark on a massive defoliation campaign, and. . .er, burn down all the forests. I think you’ll all agree that’s a sensible move under the circumstances.”